Togetherness and Solitude

The Machine Will Never Triumph, part forty

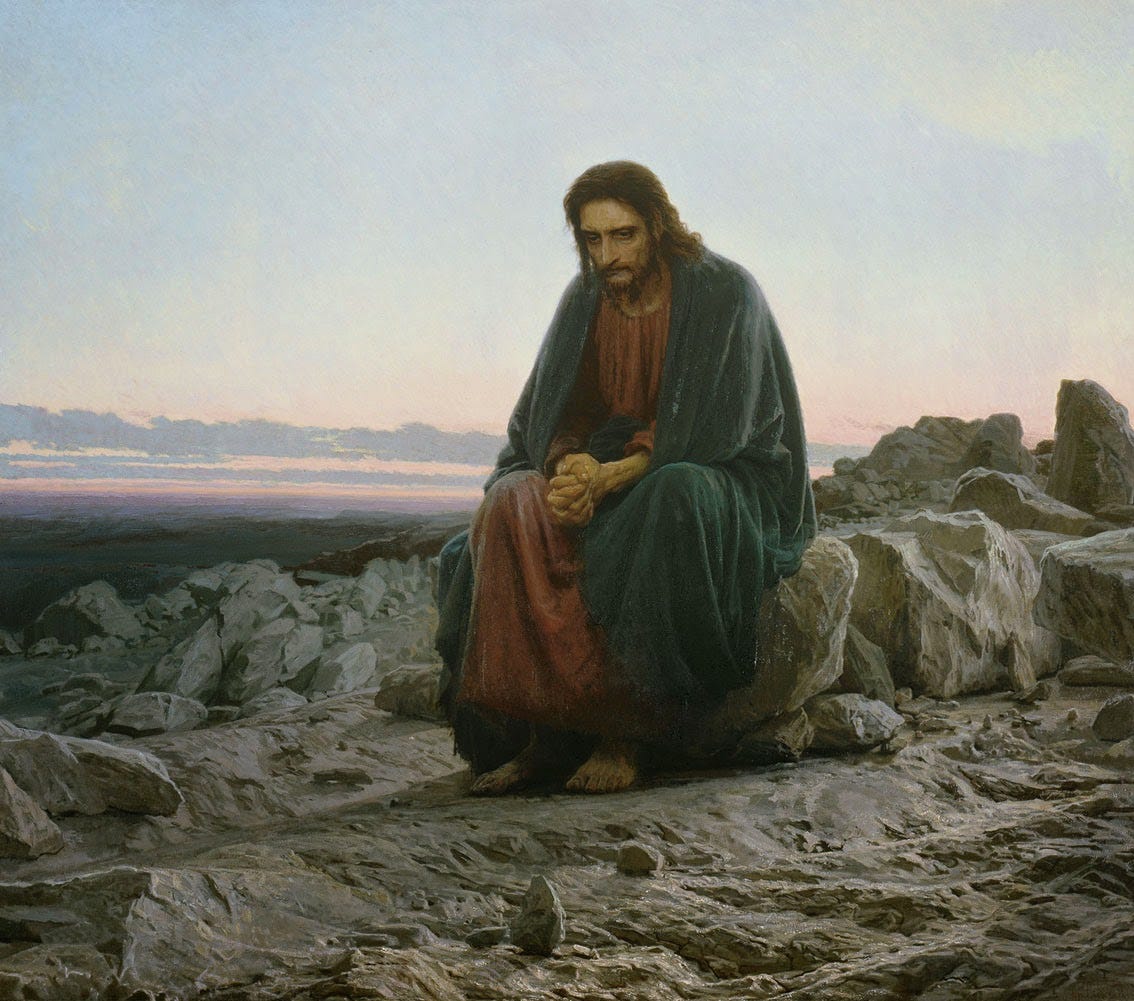

Noli me tangere—

Noli me tangere, touch me not!

O you creatures of mind, don’t touch me!

O you with mental fingers, O never put your hand on me!

O you with mental bodies, stay a little distance from me!

And let us, if you will, talk and mingle

in mental contact, gay and sad.

But only that.

O don’t confuse

the body into it, let us stay apart.

Great is my need to be chaste

and apart, in this cerebral age.

Great is my need to be untouched

untouched.

Noli me tangere!1

Just as Jesus requested not to be touched, so did Lawrence, but not from all people. Lawrence felt that only the touch from modern, cerebral people was unclean. Simple people who live according to traditional ways, who are in touch with the cosmos, the land, and the Divine, do not poison through their touch. All men may be humans, but the touch of a sun-man heals, whereas the touch of a robot kills. In this day and age, when most people are less like the Gods, and more like machines, the best thing may be to avoid other people. “The world is lovely if one avoids man—so why not avoid him! Why not! Why not! I am tired of humanity.”2

Moderns view the past as being repressive and full of laws, and our era as being free. However, the truth is that it is we who are more bound by regulations, and the people of the past were freer. Earlier times may have had more cultural and religious norms, but they were often not codified, and they tended to be based on natural law and common sense. Even passports didn’t exist until after the First World War. Now, on the other hand, society is full of so many systems, and those systems need laws and rules to function, so we live—but tied into straightjackets. With ever present surveillance, and complete lack of privacy, one wrong move may ruin one’s life. One is no longer even free to share opinions in case they may be viewed as politically incorrect. The only freedoms modern people are allowed are the freedoms to waste life, waste time, and destroy their minds with drugs. It is time to move back to simpler, freer times. As Lawrence writes:

Could any law put into being something which did not before exist? It could not. Law can only modify the conditions, for better or worse, of that which already exists.

But law is a very, very clumsy and mechanical instrument, and we people are very, very delicate and subtle beings. Therefore I only ask that the law shall leave me alone as much as possible. I insist that no law shall have immediate power over me, either for my good or for my ill. And I would wish that many laws be unmade, and no more laws made. Let there be a parliament of men and women for the careful and gradual unmaking of laws.3

For one who would claim that this is tantamount to anarchy, we would state that Lawrence believed in a cosmological aristocracy of sun-men, not in anarchy. If anything, the modern world is anarchistic, despite its laws. “In fact, there is no anarchy so horrid as the anarchy of fixed law, which is mechanism.”4

Loneliness

I never know what people mean when they complain of loneliness.

To be alone is one of life’s greatest delights, thinking one’s own thoughts,

doing one’s own little jobs, seeing the world beyond

and feeling oneself uninterrupted in the rooted connection

with the centre of all things.5

One of the great joys of life until approximately one hundred years ago was the joy of silence, peace, and being alone. Everyone needs these moments of retreat from others and the world. Some, such as monks, would live their entire lives in such a state. Now, we feel we need radio, television, and other distractions. Modern people don’t believe in a God, nor the soul, nor the afterlife, so they feel extremely depressed at any moment they have time to ponder the nature of life, so they choose not to think, and they drug themselves into a stupor through the use of entertainment and drugs. This may prevent them from committing suicide, but it cuts off the last remaining connections to the cosmos from an already uprooted person, leading to a deadness of the soul. And what of the men and women who do retain roots and who strive to re-establish connections to the world? It will be a difficult time, since there is really nowhere left in the world with complete peace, and the last remaining refuges of peace are being ground to dust by the Machine. As Lawrence writes:

He went down again into the darkness and seclusion of the wood. But he knew that the seclusion of the wood was illusory. The industrial noises broke the solitude, the sharp lights, though unseen, mocked it. A man could no longer be private and withdrawn. The world allows no hermits. […]

The fault lay there, out there, in those evil electric lights and diabolical rattlings of engines. There, in the world of the mechanical greedy, greedy mechanism and mechanised greed, sparkling with lights and gushing hot metal and roaring with traffic, there lay the vast evil thing, ready to destroy whatever did not conform. Soon it would destroy the wood, and the bluebells would spring no more. All vulnerable things must perish under the rolling and running of iron.6

In the not too distant past, even cities were places where peace could be had. Not long ago there were no electric lights, telephones, radios, or automobiles. Village and country life was always superior, but there was peace even in cities. Now, even the remotest places on earth are trampled under the tread of the Machine. The advent of modern devices, such as the electric light, though seemingly innocuous to many, has brought great horrors upon the world. It even changes how we think. When the flick of the switch gives off the seeming power of the sun, the sun stops meaning anything, but then one tries to escape, go on a hike, or travel, but all the excitement has gone out of us. In the end, many people simply waste away their lives in front of a screen, knowing nothing better; a point which Heidegger makes as follows:

[T]he modern metropolis, even before the war, had already turned night into day by means of a technology of illumination, so that neither the sky nor the lights that belong to it can be seen. As a result of this lighting technology, brightness itself has become an object that can be produced. Brightness, in the sense of the inconspicuous in all shining, has lost its essence[…] (The modern human is fascinated by this technological monstrosity of brightness; when it becomes too much, he uses the mountains or the sea as a palliative; he then “experiences” “nature,” an experience that certainly can become boring already on the first morning of the trip, whereupon he just goes to the movies. Ah, the totality of what is called “life”!)7

In these last days of our era, before the end comes, and before something new arises, the best we can do, perhaps, is to follow Jeffers’ advice, and spend time in what remains of nature, getting whatever sustenance we can:

Walk on gaunt shores and avoid the people; rock and wave are good

prophets;

Wise are the wings of the gull, pleasant her song.8

Delight of being alone.

I know no greater delight than the sheer delight of being alone.

It makes me realise the delicious pleasure of the moon

that she has in travelling by herself, throughout time,

or the splendid growing of an ash-tree

alone, on a hill-side in the north, humming in the wind.9

Being along is such a joy precisely because one who is in touch with things is never alone. Even that tree on a hill is connected to the earth, the sun, water, and various small creatures. The only man who is truly alone is the man who severs his connections and drowns his life in noise. As for getting away from people for a time, it is a great joy, since the peace allows one time to gather one’s thoughts and get back in touch with the earth, the sun, the moon, and the stars. It is exceedingly difficult for sane people to stay in touch with the Divine in modern cities, which is why sane people should leave insane places. “People are queer everywhere, and the world is going quite insane. But there are still a few quiet places that are livable.”10 It is our urgent responsibility to find those places and to keep them sacred. Ultimately, we are on a journey towards the Gods, and that, in the case of the modern world, is a journey away from most people. As Lawrence writes: “I was out on the road again, thanking God for the blessing of a road that belongs to no man, and travels away from all men.”11

Lonely, lonesome, loney-o!

When I hear somebody complain of being lonely

or, in American, lonesome

I really wonder and wonder what they mean.

Do they mean they are a great deal alone?

But what is lovelier than to be alone?

escaping the petrol fumes of human conversation

and the exhaust-smell of people

and be alone!

Be alone, and feel the trees silently growing.

Be alone, and see the moonlight outside, white and busy and silent.

Be quite alone, and feel the living cosmos softly rocking

soothing and restoring and healing.

Soothed, restored and healed

when I am alone with the silent great cosmos

and there is no grating of people with their presences gnawing

at the stillness of the air.12

To be alone with the earth, sun, moon, and trees is a great thing. To be alone with the Gods is even greater. Companionship with other people may be a human desire, but it is not a human need. Companionship with other people is only a joy if those others are also in touch with the Divine. As for the robot masses, it is best to escape as far away from them as possible. Modern men and women fear death above all else. That is why we have so many infernal inventions; that is why we have cities full of towers of Babel. If a person fears death, and if that person cannot find meaning in life, he or she can either choose to drown out their sorrow or face it directly. The former path is the path of the many, and is the path the modern world has taken. Modern people never allow themselves a single moment of peace, silence, or rest. As for the latter category, examples are many saints and sages who faced their doubts and thereby found enlightenment. The path of facing one’s fears is difficult and it may lead to a dark night of the soul, but the reward is beyond description. Turn off your devices, get away, find silence, find peace, and you, as a child of the modern world, will know fear, anxiety, depression. You may even, like Tolstoy, consider suicide. But, if you face those fears and humble yourself before the natural world and the various manifestations of the Divine, you will come through, just like Tolstoy, and you may have a resplendent vision of the Gods. Lawrence describes the choice as follows:

When, in the city, you wear your white spats and dodge the traffic with the fear of death down your spine, then you are quite safe from the terrors of infinite time, The moment is your little islet in time, it is the spatial universe that careers around you.

But once you isolate yourself on a little island in the sea of space, and the moment begins to heave and expand in great circles, the solid earth is gone, and your slippery, naked dark soul finds herself out in the timeless world, where the chariots of the so-called dead dash down the old streets of centuries, and souls crowd on the footways that we, in the moment, call bygone years. The souls of all the dead are alive again, and pulsating actively around you. You are out in the other infinity.13

The breath of life.

The breath of life is in the sharp winds of change

mingled with the breath of destruction.

But if you want to breathe deep, sumptuous life

breathe all alone, in silence, in the dark,

and see nothing.14

Breathe. Breathe alone and in peace, and look inside yourself. This is an instruction given by every authentic religion, and Lawrence gives this instruction as well. To live you must breathe, but to know yourself, you must have peace and solitude—to get within yourself. Since the one contains the many, and the many the one, if you come to know your soul, you will come to know the Gods. Once you come to know the Gods, truly know the Gods, you will come to know peace everywhere, even in the diabolical cities. You will be untouchable by the mechanical people:

Not to be touched by any, any of the mechanical cog-wheel people. To be left alone, not to be touched. To hide, and be hidden, and never really be spoken to. […] To shut doors of iron against the mechanical world. But to let the sunwise world steal across to her, and add its motion to her, the motion of the stress of life, with the big sun and the stars like a tree holding out its leaves.15

Bibliography

Heidegger, Martin. Heraclitus. Translated by Julia Goeser Assaiante and S. Montgomery Ewegen. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

Jeffers, Robinson. The Collected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers. Edited by Tim Hunt. Vol. Three. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1988.

Lawrence, D. H. Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Edited by Michael Squires. London: Penguin Books, 2009.

———. Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays. Edited by Michael Herbert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

———. Study of Thomas Hardy and Other Essays. Edited by Bruce Steele. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

———. The Letters of D. H. Lawrence. Edited by Keith Sagar and James T. Boulton. Vol. VII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

———. “The Man Who Loved Islands.” In Collected Stories, 1171–93. London: Everyman’s Library, 1994.

———. The Plumed Serpent. Edited by L. D. Clark. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

———. The Poems. Edited by Christopher Pollnitz. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

———. Twilight in Italy and Other Essays. Edited by Paul Eggert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

D. H. Lawrence, The Poems, ed. Christopher Pollnitz, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 406–7.

D. H. Lawrence, The Letters of D. H. Lawrence, ed. Keith Sagar and James T. Boulton, vol. VII (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 276.

D. H. Lawrence, Study of Thomas Hardy and Other Essays, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 14.

D. H. Lawrence, Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays, ed. Michael Herbert (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 29.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:525.

D. H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, ed. Michael Squires (London: Penguin Books, 2009), 119.

Martin Heidegger, Heraclitus, trans. Julia Goeser Assaiante and S. Montgomery Ewegen (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), 108.

Robinson Jeffers, The Collected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers, ed. Tim Hunt, vol. Three (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1988), 118.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:525.

Lawrence, The Letters of D. H. Lawrence, VII:506.

D. H. Lawrence, Twilight in Italy and Other Essays, ed. Paul Eggert (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 204.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:556–57.

D. H. Lawrence, “The Man Who Loved Islands,” in Collected Stories (London: Everyman’s Library, 1994), 1172–73.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:612.

D. H. Lawrence, The Plumed Serpent, ed. L. D. Clark (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 104.

Very good, this one.

I am leaving soon on a trip to the great deserts of Utah, which remain very wild. I will pass through some of the New Mexican landscapes that Lawrence loved. I love the desert. There is a place in Utah I particularly enjoy, called the Valley of the Gods - it is a name you will particularly appreciate :) It is a place that is holy to the Navajos, and a very wild landscape of red rock towers.

Btw, I hope you heal your rift with David Bentley Hart. You both have important things to say. Hart can be a bit arrogant, harsh, and moralistic, but he is a great man and his heart is in the right place. We must forgive people like that their foibles. And his uncompromising insistence on an elevated moral vision is an important counterweight to so much of the moral shittiness we encounter today.

And while I think your heart is definitely in the right place too, you sometimes veer too close to a kind of moral callousness, perhaps, in your - completely justified - disgust with modernity and yearning for a vitality and exuberance we have lost - forgive me for saying so, but it does seem to me that way. But you too have an indispensable message, too, that needs more exposure.

I particularly liked Lonely, lonesome, loney-o! Thanks for that. Really related to this post.

Yes the area around Taos and Santa Fe is magical. Only been once but it stays with me.