The Need for Rananim

The Machine Will Never Triumph, part forty-five

Give us the Thebaid.

Modern society is a mill

that grinds life very small.

The upper millstone of the robot-classes,

the lower millstone of the robot-masses,

and between them, the last living human beings

being ground exceeding small.

Turn away, O turn away, man of flesh!

Slip out, O slip out from between the millstones

extract and extricate yourself

and hide in your own wild Thebaid.

Then let the millstones grind, for they cannot stop grinding, so let them

grind

without grist.

Let them grind on one another, upper-class robot weight upon lower-class

robot weight

till they grow hot, and burst, as even stone can explode.1

The modern world is itself like an inanimate machine made to destroy man. The two main parts of this modern machinery are the owners of the means of production and the workers. Despite their differences, almost all people from both classes interact like robots. Whether the society is communist, capitalist, or some other system, each state in the modern world has upper and lower classes, and those classes grind upon each other, destroying real men in the process. So long as we take part in the functioning of the modern world, the machine-like character of the modern world will slowly but surely destroy us. And so the goal for any man who avoided a robot-like existence is to escape. A man who is not a robot and who sees the Gods within the trees and behind the sun cannot maintain his integrity as a part of this diabolical world. To consume modern products, or to work for a company earning a wage—even to own that company—is propping up a devilish system that needs to crumble to the ground. As such, we must escape, and escape quickly. But escape to where? Lawrence proposed intentional communities of people who love life, worship the Gods, and hate the Machine. These communities he called Rananim. If enough people left the modern world and escaped to Rananim just as the Desert Fathers escaped to the Thebaid,2 the various systems that make up the Machine would start failing one by one, and the modern edifice would come down.

The necessity of communities, such as Rananim, was believed in not just by Lawrence, but many of the other luminaries quoted in this text. Heidegger, for instance, stated the following: “‘Cells’ of resistance will be formed everywhere against technology’s unchecked power. They will keep reflection alive inconspicuously and will prepare the reversal, for which ‘one’ will clamor when the general desolation becomes unbearable.”3 The reign of technology is currently virtually unchecked as it spreads out its life-destroying tentacles across the entire globe. These “cells” or communities will not exist for a head-on fight with the system, but will exist in order to keep spiritual reflection alive, and in order to have a group of people prepared for the end of the modern world. Rananim will be a place outside time, where all of the best of the past and present will harmoniously exist. It will be a place for living, teaching, loving, and craftsmanship. There will be no money in Rananim, and it will have no systems as such—for example: systems of government or a structured economy—but will be organized naturally and organically in a hierarchical structure with the most qualified and selfless individual of spiritual integrity at the top (the chief sun-man), aided by others of such qualities. Eventually, the modern world will destroy itself, and then people will clamor for its urgent end and the rise of something new, but they will not know how to begin, so the people of Rananim can usher in the new era. First we build Rananim, then the rest will follow: “[A]ll that remains is to be a Noah, and build an ark. An ark, an ark, my kingdom for an ark! An ark of the covenant, into which also the animals shall go in two by two, for there’s one more river to cross!”4

For every individual living today, a choice must be made: the pleasures of the modern world at the expense of the eternal life of the soul, or the sacrifices required to withdraw to Rananim, and the eternal pleasure of the Gods. It is either one or the other: there are no middle roads. Lawrence describes this choice as follows:

I am attempting the impossible. I had better either go and take my pleasure of life while it lasts, hopeless of the pleasure which is beyond all pleasures. Or else I had better go into the desert and take my way all alone, to the Star where at last I have my wholeness, holiness. The way of the anchorites and the men who went into the wilderness to pray.—For surely my soul is craving for her consummation, and I am weary of the thing men call life. Living, I want to depart to where I am.5

To choose the harder path, the path of Rananim, is to put one’s soul into the hands of the Gods, and to know that pleasure given up in this life leads to the soul’s repose with the Fire beyond being, and “the pleasure which is beyond all pleasures.” Lawrence was not the first man to advocate for this, but he is the strongest advocate for this path in the modern era. Ancient Christians, such as the Desert Fathers, knew what needed to be done, prior to the debasement of Christianity once it became a religion of the classes and masses. Rananim, if it teaches nothing else, should be a place where a person can learn how to give up having and learn to start being.

Side-step, O sons of men!

Sons of men, from the wombs of wistful women,

not piston-mechanical-begotten,

sons of men, with the wondering eyes of life

hark! hark! step aside silently and swiftly.

The machine has got you, is turning you round and round

and confusing you, and feeding itself on your life.

Softly, subtly, secretly, in soul first, then in spirit, then in body

slip aside, slip out

from the entanglement of the giggling machine

that sprawls across the earth in iron imbecility.

Softly, subtly, secretly, saying nothing

step aside, step out of it, it is eating you up,

O step aside, with decision, sons of men, with decision.6

The Machine is destroying both the world and individuals within the world. Each and every person has the choice to become a robot or to become a man of the sun (or at least a man of a man of the sun). Escape is never easy, but everyone can escape the iron clutches of the Machine. First one must escape in soul, then mind, then body. The former two mean that one may be in the modern world but not of the modern world; but to finally, bodily escape means making the final choice to leave for Rananim. It would not take much for Rananim to get started: at first only a few people are needed. It would be a place of love, education, and communing with nature. Lawrence described some of his plans as follows:

We talk and make plans: plans of coming back to the ranch and having places near one another—and perhaps having a sort of old school, like the Greek philosophers, talks in the garden—that is, under the pine-trees. I feel I might perhaps get going with a few young people, building up a new unit of life out there, making a new concept of life. Who knows!7

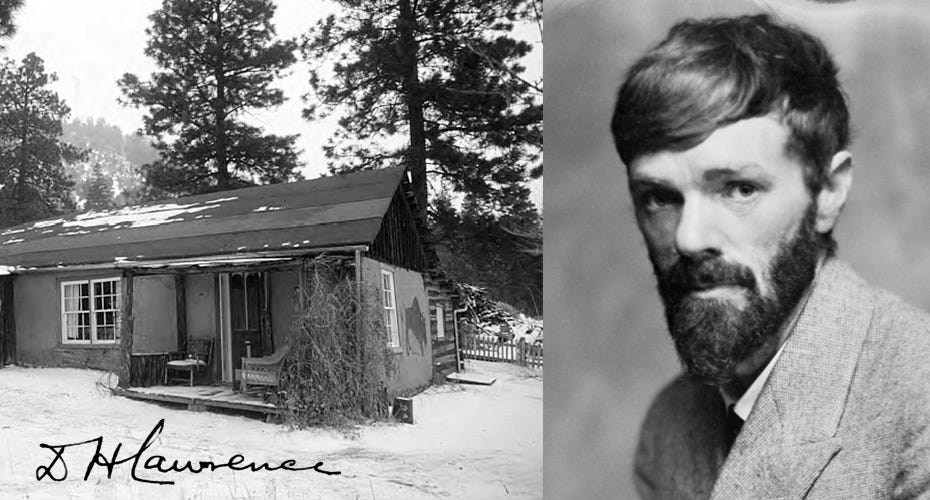

Even though those plans never came to fruition physically, they did come to fruition spiritually. The Lawrence Ranch outside of Taos, NM, is still a very spiritually powerful place, where one with an open heart and open mind may be able to experience the living presence of Lawrence here and now, just as the present author did. If you think all of this sounds too hard, it is not. Lawrence described much of what Rananim should look like as follows:

If you could only tell them that living and spending aren’t the same thing! But it’s no good. If only they were educated to live instead of earn and spend, they could manage very happily on twenty-five shillings. If the men wore scarlet trousers as I said, they wouldn’t think so much of money: if they could dance and hop and skip, and sing and swagger and be handsome, they could do with very little cash. […] They ought to learn to be naked and handsome, and to sing in a mass and dance the old group dances, and carve the stools they sit on, and embroider their own emblems. Then they wouldn’t need money. And that’s the only way to solve the industrial problem: train the people to be able to live and live in handsomeness, without needing to spend. But you can’t do it. They’re all one-track minds nowadays. Whereas the mass of people oughtn’t even to try to think—because they can’t. They should be alive and frisky, and acknowledge the great god Pan. He’s the only god for the masses, forever. The few can go in for higher cults if they like. But let the mass be forever pagan. […]

But the colliers aren’t pagan—far from it. They’re a sad lot, a deadened lot of men: dead to their women, dead to life. The young ones scoot about on motor-bikes with girls, and jazz when they get a chance, But they’re very dead. And it needs money. Money poisons you when you’ve got it, and starves you when you haven’t. […]

I feel great grasping white hands in the air, wanting to get hold of the throat of anybody who tries to live, to live beyond money, and squeeze the life out. There’s a bad time coming. There’s a bad time coming, boys, there’s a bad time coming! If things go on as they are, there’s nothing lies in the future but death and destruction, for these industrial masses.8

Life is about living, real, direct, vivid life in touch with things. It is not about having, buying, or spending. If people could learn to do things for themselves, and learned a renewed appreciation of beauty, they would no longer need to buy and consume. To make your own cup, no matter how imperfect, is a vastly superior feeling to buying one off the shelf. Rananim would exist for many reasons, but one would be to teach people how to live in a simple, beautiful, and self-sufficient manner. As for religion, Rananim would be open to people of all faiths, so long as they accept the validity of other faiths grounded in perennial wisdom. For many, the cult of Pan, as Lawrence stated above, would be ideal, due to its beauty and simplicity, along with its emphatic insistence that the presence of the Gods is among us, in everything, here and now. As for more theologically minded men, they may be Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Jews, and indigenous primordialists, including those of ancient Egypt, Greece, the Andes, and Ireland. But the sun-men, even while affiliated with different orthodox traditions, will be devoted fundamentally to the Heraclitean religion of the primordial Fire. When the bad times come, the Fire will burn all things down, but from the ashes comes the phoenix, symbol of resurrection and renewal.

Departure

Now some men must get up and depart

from evil, or all is lost.

The evil will in many evil men

makes an evil world-soul, which purposes

to reduce the world to grey ash.

Wheels are evil

and machines are evil

and the will to make money is evil.

All forms of abstraction are evil:

finance is a great evil abstraction

science has now become an evil abstraction

education is an evil abstraction.

Jazz and film and wireless

are all evil abstractions from life.

And politics, now, are an evil abstraction from life.

Evil is upon us and has got hold of us.

Men must depart from it, or all is lost.

We must make an isle impregnable

against evil.9

In the preceding passage, Lawrence gave us his concise definition of evil, and stated that humans must choose to put their evil ways behind them or risk losing everything. The individual must first look deep inside his or her soul, and then make outward changes, finally coming together into communities of people who have resolved to be finished with evil.

When many or most men and women give themselves over to evil, a greater evil comes into being; an evil far more diabolical than the sum of individual men’s evils. This evil force becomes an anti-god or antichrist, and is prophesied throughout many religious traditions, such as the Gnostics. Its name has changed over the years, but we call it the Machine. Life is good, so the principal objective of the Machine is to wipe out all life on this planet. Anything that contributes to that is evil: automobiles, all machines, money, television, and computers are evil. Not only objects, but certain attitudes are evil: greed, hubris, and rationalism are evil. Anything built on those objects or attitudes is evil as well, so modern science, education, entertainment, and politics are all evil. There is only one way out: Rananim. We must build up Rananim as a great fortress against these modern evils, and the great evil of the Machine.

Starting something new is never easy. Many well-intentioned communities have failed, so we now tend to have the modern pretense to think that all communities will fail. Rananim may fail, but the modern world will fail, and so we must do something, and try with whatever effort we have to build Rananim, since it is our only hope. In the following passage Lawrence describes some of his ideas for the founding of Rananim:

I feel how very hard it is to get anything real going. Until a few men have an active feeling that the world, the social world, can offer little or nothing any more; and until there can be some tangible desire for a new sort of relationship, between people; one is bound to beat about the bush. It is difficult not to fall into preciosity and a sort of faddism.

I think, one day, I shall take a place in the country, somewhere where perhaps one or two other men might like to settle in the neighbourhood, and we might possibly slowly evolve a new rhythm of life: learn to make the creative pauses, and learn to dance and to sing together, without stunting, and perhaps also publish some little fighting periodical, keeping fully alert and alive to the world, living a different life in the midst of it, not merely apart. You see one cannot suddenly decapitate oneself. If barren idealism and intellectualism are a curse, it’s not the head’s fault. The head is really a quite sensible member, which knows what’s what: or must know. One needs to establish a fuller relationship between oneself and the universe, and between oneself and ones [sic] fellow man and fellow woman. It doesn’t mean cutting out the “brothers in Christ” business simply: it means expanding it into a full relationship, where there can be also physical and passional meeting, as there used to be in the old dances and rituals. We have to know how to go out and meet one another, upon the third ground, the holy ground. […] We need to come forth and meet in the essential physical self, on some third holy ground. It used to be done in the old rituals, in the old dances, in the old fights between men. It could be done again. But the intelligent soul has to find the way in which to do it: it won’t do itself. One has to be most intensely conscious: but not intellectual or ideal.10

Rananim would be a society based on tenderness, togetherness—and solitude when appropriate—love for the Divine in all its manifestations, and a love of life. There would be no education in the modern sense, but traditions would be passed down organically to those who show the aptitude. A shoemaker would make beautiful shoes for love of the craft, and there would be free exchange between craftsmen, without money ever tainting things. There would be a revival of all the old crafts and traditions. People would come together again around the mystical fire to dance, sing, and tell tales of mystery and wonder. Rananim will not be a secular community, but will be hallowed, sacred ground, where worship of all of the Gods takes place. We have let the mystery of life depart from the world, so, in time, Rananim will be a place for the Gods to show themselves again, and for the mysteries to be re-revealed, which, in turn, will further awaken the people. Rananim will be wholly sacred, with every house being a house of the Gods, and every tree being part of a vast, sacred grove. We can make this happen, but only if we get out of our heads and start feeling more and thinking less. Only then may we come back into touch with the cosmos.

The world is ending, so we must be ready: “Now we’ve got the sulks, and are waiting for the flood to come and wash out our world and our civilisation. All right, let it come. But somebody’s got to be ready with Noah’s Ark.”11 All of the so-called “improvements” in modern life have impoverished us in various ways. Every time a light switch is flicked on or a water tap is turned, some of the creative imagination flies away from the world. There is no point in a world with so many inventions if those inventions rape mother earth, and chain our hearts and souls. This is why we need to stop and turn around, and Rananim is the best and only first step in that direction. Our need for this change is poetically portrayed by R. S. Thomas as follows:

As life improved, their poems

Grew sadder and sadder. Was there oil

For the machine? It was

The vinegar in the poets’ cup.

The tins marched to the music

Of the conveyor belt. A billion

Mouths opened. Production,

Production, the wheels

Whistled. Among the forests

Of metal the one human

Sound was the lament of

The poets for deciduous language.12

Temples.

Oh, what we want on earth

is centres here and there of silence and forgetting,

where we may cease from knowing, and, as far as we know,

may cease from being

in the sweet wholeness of oblivion.13

If, after the preceding descriptions, you think Rananim would be a political entity, you are wrong. Rananim would exist as much for the salvation of individual souls as for the salvation of the world. Rananim would not be one monolith, but a seed that flies into the wind, fructifying the earth. May a thousand Rananims bloom. Rananim would be a place for people to come together and work at crafts, dance, and pray to the Gods, but it would also be a great monastery, where people may leave off knowing in the rationalistic and empirical manners they are used to, and would come to know, in sweet moments of silence, the oblivion that is fullness beyond compare. What the Buddhists call Nirvana is not the end goal of existence, but the calm of the soul before it is flooded with the light of the primordial Fire. As Spengler writes in the following passage, the end times are also a time of opportunity for a reawakening; a time when Being will make its reappearance:

With the formed state, high history also lays itself down weary to sleep. Man becomes a plant again, adhering to the soil, dumb and enduring. The timeless village and the “eternal” peasant reappear, begetting children and burying seed in Mother Earth—a busy, easily contented swarm, over which the tempest of soldier-emperors passingly blows. In the midst of the land lie the old world-cities, empty receptacles of an extinguished soul, in which a historyless mankind slowly nests itself. Men live from hand to mouth, with petty thrifts and petty fortunes, and endure. Masses are trampled on in the conflicts of the conquerors who contend for the power and the spoil of this world, but the survivors fill up the gaps with a primitive fertility and suffer on. And while in high places there is eternal alternance of victory and defeat, those in the depths pray, pray with that mighty piety of the Second Religiousness that has overcome all doubts for ever. There, in the souls, world-peace, the peace of God, the bliss of grey-haired monks and hermits, is become actual—and there alone. It has awakened that depth in the endurance of suffering which the historical man in the thousand years of his development has never known. Only with the end of grand History does holy, still Being reappear. It is a drama noble in its aimlessness, noble and aimless as the course of the stars, the rotation of the earth, and alternance of land and sea, of ice and virgin forest upon its face. We may marvel at it or we may lament it—but so it is.14

As Spengler declared, the end of the world will not come easy, and for many long years there will be battles over trifles. But, for those few who come together in communities such as Rananim, there will be peace both on earth and in the souls of men. The simple-living monks and hermits of Rananim will endure, no matter what happens, in the eternal repose of the Gods. Rananim is not a new concept, but it is a novel concept for moderns. Medieval monasteries, ancient temple grounds, and various sacred places in various times and places all had similar goals. What we need to do is to somehow delve deeply into our souls to find the Gods, and then with the mysteries they impart to us, we must build temples and oracles in their name: Rananim. As Lawrence writes:

There needs a centre of silence, and a heart of darkness[.] We’ll have to establish some spot on earth, that will be the fissure into the under world, like the oracle at Delphos, where one can always come to. I will try to do it myself. […] And then one must set out and learn a deep discipline—and learn dances from all the world, and take whatsoever we can make into our own. And learn music the same; mass music, and canons, and wordless music like the Indians have. And try—keep on trying. It’s a thing one has to feel one’s way into. And perhaps work a small farm at the same time, to make the living cheap.15

It would not take much to get started: only a few people with faith and some effort could radically change the world. And how does this come to be? First and foremost, men must find the dark Gods within their breasts, and the dark Gods, unknowable, beyond being. Human love can be beautiful, but when two worshipers of the dark Gods come together in worship, then sparks fly! One must find the Gods alone. Churches, temples, and religious communities are important, but communion with one of the dark Gods only happens alone, and it is between a man’s soul and his God. But, once one becomes a worshiper of a God, he can meet with others in worship, and attain to a sacred contact that is beyond words.

Man’s isolation was always a supreme truth and fact, not to be forsworn. And the mystery of apartness. And the greater mystery of the dark God beyond a man, the God that gives a man passion, and the dark, unexplained blood-tenderness that is deeper than love, but so much more obscure, impersonal, and the brave, silent blood-pride, knowing his own separateness, and the sword-strength of his derivation from the dark God. This dark, passionate religiousness and inward sense of an indwelling magnificence, direct flow from the unknowable God, this filled Richard’s heart first, and human love seemed such a fighting for candle-light, when the dark is so much better. To meet another dark worshipper, that would be the best of human meetings[…]

Man’s ultimate love for man? Yes, yes, but only in the separate darkness of man’s love for the present, unknowable God. Human love, as a god-act, very well. Human love as a ritual offering to the God who is out of the light, well and good. But human love as an all-in-all, ah, no, the strain and the unreality of it were too great[…]

The only thing one can stick to is one’s own isolate being, and the God in whom it is rooted. And the only thing to look to is the God who fulfils one from the dark. And the only thing to wait for is for men to find their aloneness and their God in the darkness. Then one can meet as worshippers, in a sacred contact in the dark.16

And this is what Rananim is all about: a place where men and women may come in silence to find the Gods, and then come together in communion. “We must start on a new venture towards God.”17 When we think this is too much, or too hard, we must take strength from past examples of courage from men who sought and found a God in the darkness, such as many of the monks of the Middle Ages:

In the howling wilderness of slaughter and débâcle, tiny monasteries of monks, too obscure and poor to plunder, kept the eternal light of man’s undying effort at consciousness alive. A few poor bishops wandering through the chaos, linking up the courage of these men of thought and prayer. A scattered, tiny minority of men who had found a new way to God, to the life-source, glad to get again into touch with the Great God, glad to know the way and to keep the knowledge burningly alive.18

Bibliography

Heidegger, Martin. Zollikon Seminars: Protocols, Conversations, Letters. Edited by Medard Boss Franz Mayr and Richard Askay. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2001.

Lawrence, D. H. Introductions and Reviews. Edited by N. H. Reeve and John Worthen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

———. Kangaroo. Melbourne: The Text Publishing Company, 2018.

———. Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Edited by Michael Squires. London: Penguin Books, 2009.

———. Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays. Edited by Michael Herbert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

———. The Letters of D. H. Lawrence. Edited by Keith Sagar and James T. Boulton. Vol. VII. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

———. The Letters of D. H. Lawrence. Edited by James T. Boulton and Lindeth Vasey. Vol. V. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

———. The Plumed Serpent. Edited by L. D. Clark. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

———. The Poems. Edited by Christopher Pollnitz. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Spengler, Oswald. The Decline of the West. Edited by Arthur Helps and Helmut Werner. Translated by Charles Francis Atkinson. New York: Vintage Books, 2006.

Thomas, R. S. Collected Poems. London: Orion Books, 2000.

D. H. Lawrence, The Poems, ed. Christopher Pollnitz, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 553.

A region surrounding the ancient city of Thebes, along the Nile River.

Martin Heidegger, Zollikon Seminars: Protocols, Conversations, Letters, ed. Medard Boss Franz Mayr and Richard Askay (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2001), 283.

D. H. Lawrence, Introductions and Reviews, ed. N. H. Reeve and John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 91.

D. H. Lawrence, The Plumed Serpent, ed. L. D. Clark (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 254.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:554.

D. H. Lawrence, The Letters of D. H. Lawrence, ed. Keith Sagar and James T. Boulton, vol. VII (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 616.

D. H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, ed. Michael Squires (London: Penguin Books, 2009), 299–300.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:629.

D. H. Lawrence, The Letters of D. H. Lawrence, ed. James T. Boulton and Lindeth Vasey, vol. V (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 552–53.

D. H. Lawrence, Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays, ed. Michael Herbert (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 199.

R. S. Thomas, Collected Poems (London: Orion Books, 2000), 225.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:640.

Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, ed. Arthur Helps and Helmut Werner, trans. Charles Francis Atkinson (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), 381.

Lawrence, The Letters of D. H. Lawrence, V:591.

D. H. Lawrence, Kangaroo (Melbourne: The Text Publishing Company, 2018), 376–77.

Lawrence, Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays, 200.

ibid., 207.

Thanks, Farasha. Your post reminded me of Richard Gregg, the American Gandhian whose biography I reviewed recently. In the 1920's, he spent several years with Gandhi at his ashram, which was an intentional community of sorts. Out of that experience, he wrote several books, including The Value of Voluntary Simplicity, the idea of which is implicit in Lawrence's and your description, it seems to me. In the past, you told me that DHL referred to Gandhi, and so I was wondering if the ashram idea had contributed to his thinking. That aside, but in a similar vein, I've just visited a beautiful 'chiesa rupestra' in a gravina in Mottola, Puglia, where a tiny community of early Christians hid from the Moors. DHL would surely have seen similar things during his time in Italy, no? (P.S. It appears that I can no longer 'like' your posts, but rest assured that I do).

I wonder if it's something like this that Eric Gill, David Jones and others were trying to build in the 1920s with their artistic retreat centre at Capel-y-ffin?

Pope Benedict was thinking along analogous lines, I feel, in his 1969 prophecy of a Church grown small and purified due to persecution and neglect: 'Men in a totally planned world will find themselves unspeakably lonely. If they have completely lost sight of God, they will feel the whole horror of their poverty. Then they will discover the little flock of believers as something wholly new. They will discover it as a hope that is meant for them, an answer for which they have always been searching in secret.'

Eventually the tide will turn. And that's when Rananim comes into its own.