Sermon Against the Machine

A Christian existentialist exhortation to live life to its fullest and to reject technology

White field. A raven dives

from the milky smoke.

Do you see him, Ana, my little girl?

In autumn around here the golden story wound down,

the squirrel jumped, the chestnut fell.

The raven measures his step, writes in the snow

some new gospel, or maybe some celestial news

for someone who might pass through the country

and has not forgotten how to read.

We humans have.1

1. Prologue — The Congregation of the Earth

Beloved: hear now a sermon that is both indictment and funeral oration — an oration delivered at the altars of the soul and of the sod. I speak as one who will not flatter the Machine nor whisper comforts to those who have taken the Machine for their God. This sermon is Lawrencian in voice — that is to say, it will be sensuous, volcanic, unsparing; it will call the blood and the roots and the old gods into account. It is Christian in substance — that is to say, it will take sin, grace, repentance, and the unbearable fact of individual responsibility seriously. It is existential in its orientation: you are called here to choose, to suffer, to become, and to stand before God with the dignity of a conscience that will not outsource itself to instruments.

We open with confession, because confession clears the throat. Let us speak plainly: the age of the Machine has not only rearranged our cities; it has attempted to rearrange our souls. It offers efficiency for prayer, convenience for courage, and instructions for sacrifice; it offers the brain a hundred and a thousand tasks so it will never be left alone enough to hear God. The Machine tells us to be productive; God asks us to be honest. The Machine promises endless solutions; the Cross promises a single, costly Truth.

2. The Hermit Physician: A Kierkegaardian Admonition

When Kierkegaard figures himself as physician he teaches a lesson we would do well to receive. Consider the voice of inward judgment — not the bland, managerial self who signs off on productivity reports, but the examining, solitary self who knows its sins and its poverty:

[I]f I were a physician, and someone asked me, ‘What dost thou think must be done?’, I should answer, ‘The first, the unconditional condition of doing anything, and therefore the first thing to be done is, procure silence, introduce silence, God’s Word cannot be heard, and if, served by noisy expedients, it is to be shouted out clamorously so as to be heard in the midst of the din, it is no longer God’s Word. Procure silence! Everything contributes to the noise; and as it is said of a hot drink that it stirs the blood, so in our times, every event, even the most insignificant, every communication, even the most fatuous, is calculated merely to harrow the senses or to stir up the masses, the crowd, the public, to make a noise. And man, the shrewd pate, has become sleepless in the effort to find out new, ever new means for increasing the noise, for spreading abroad, with the greatest possible speed, and on the greatest possible scale, the meaningless racket. Indeed, the apogee has almost been attained: communication has just about reached the lowest point, with respect to its importance; and contemporaneously the means of communication have pretty nearly attained the highest point, with respect to quick and overwhelming distribution. For what is in such haste to get out, and on the other hand what has such widespread distribution as… twaddle? Oh, procure silence!2

The ellipses in that quotation are a mercy: they allow the conscience to step into the silence Kierkegaard knows. If we will not be physicians to our own souls — if we will not stand still long enough to be diagnosed with our cowardice, our servility to convenience, our smallness — then the Machine will prescribe for us the eternal prophylactic of distraction. That prophylactic is the opiate of measured inputs, scheduled breaths, and algorithmic consolation. Kierkegaard calls us to the hard, private work: to be examined, to be ashamed, to be healed.

3. Don Quixote and Sancho: Fear, Work, and the Danger of Sublimation

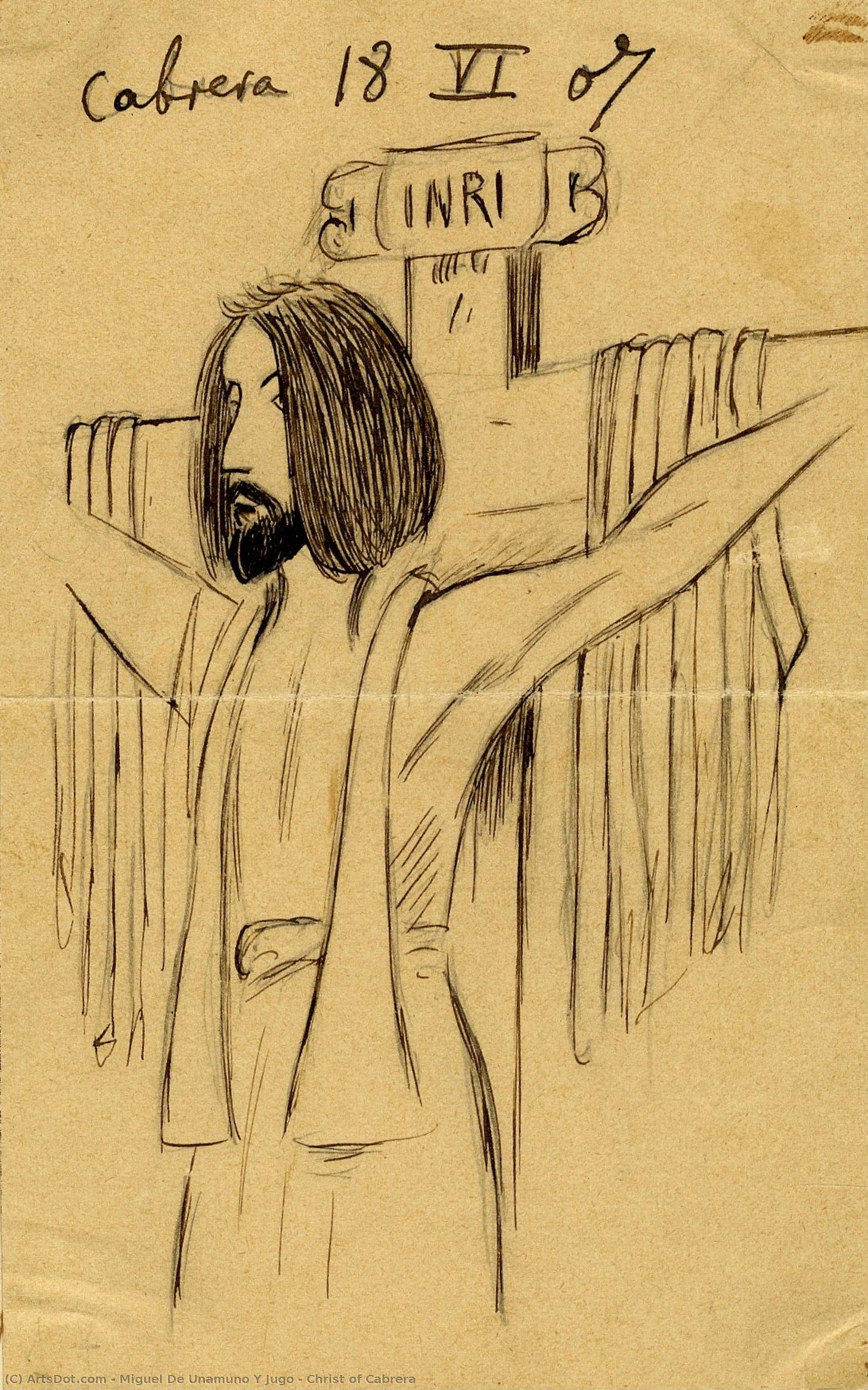

Miguel de Unamuno, calling to arms the Spanish heart, refuses the tranquilizing illusions of civilization. He sends us back into the field with Don Quixote’s madness and Sancho’s fearful sanity. Hear this, which will stoke our anger against those who domesticate life into machines and make the spirit into a caged curiosity:

The Knight was right: fear and only fear made Sancho see—makes the rest of us simple mortals see—windmills where impudent giants stand, spewing wickedness about the world. Those mills milled bread, and of that bread men confirmed in blindness ate. Today, they no longer appear to us in the form of windmills, but in the form of locomotives, dynamos, turbines, steamships, automobiles, telegraph with wires and without, machine guns, and instruments for performing ovariotomies, all conspiring to commit the same harm. Fear, and only Sanchpanzesque fear, inspires us to venerate and pay homage to steam and electricity. Fear and only Sanchpanzesque fear, makes us fall on our knees before the impudent giants of engineering and chemistry and beg them for mercy. In the end, the human species, overwhelmed by weariness and surfeit, will give up the ghost at the foot of a colossal factory manufacturing an elixir promising long life. But the bettered Don Quixote will go on living, because he sought health within himself and dared to charge the windmills.3

You can be certain, Sancho, that if at long last we are given, as you have been promised, a beatific vision of God, that vision will be a labor, a continuous and never-ending conquest of the Supreme and Infinite Truth, a constant sinking into, a plunging down under, the bottomless abysses of Eternal Life. Some will plunge more quickly into this glorious absorption than others and gain more depth and joy, but all will go on sinking into the depths without end or surcease. If we are all bound for infinitude, if we are all engaged in the process of “infinitizing” ourselves, our differences will lie in the rate of speed at which we proceed, some going faster, others slower, some believing more than others, but all of us advancing and expanding at all times as we approach the unattainable end, which no one will ever reach. And the consolation and good fortune of each one is the knowledge that he will sometime reach the point reached by someone else, while no one reaches the final point. It is best not to reach the final stage, to reach quietude, for if he who sees God dies, as the Scripture tells us, he who entirely reaches the Supreme Truth is absorbed in it and ceases to be.

Give work to Sancho, Lord, and give all of us poor mortals work always. See that we are always lashed on and that it shall always cost us an effort to conquer you and let our spirit never rest in you, lest we be annihilated and melt into your breast. Give us your paradise, Lord, but so that we may take care of it and work it, dress it, and keep it; do not give it to us to sleep in; give it to us so that we may employ eternity in conquering, eternally, step by step and inch by inch, the fathomless abysses of Your infinite bosom.4

Unamuno’s Sancho is not a technocrat. He is a creature of worry and of honest labor; fear, for him, is not a sickness but an opening. Machine culture would have us anesthetized so that fear is abolished and with it the ability to see; it would make of us Sancho without soil, Quixote whose tilt has been monetized. Work, in the Christian existential sense, is salvific when it is tethered to humility and rooted in the dirt of responsibility. It is perverse to ask that every anxiety be instrumentally removed. Fear — rightly faced — becomes the plough that turns our hearts.

4. The Critique of Civilization: Unamuno’s Curses and Our Opiates

We must take a harder look at the modern order Unamuno indicts. He sees in our civilization the false crops of wealth and noise; he names the modern narcotics plainly:

Contemporary European civilization, as it is aped everywhere, repels me. I find scientism and progressivism equally repugnant. They’re both attempts to hide deep spiritual despair, to evade the only essential problem: the immortality of the soul. Making money, activity for its own sake, and science are all opiates.

And I want to provoke and promote the tragic position, the authentically Spanish position […] of life as a dream. […] I believe we are destined to die as a people with a character of its own, but we should die fighting, affirming the ideal for which we die, the ideal which makes us unadaptable to modern civilization. We should die protesting against modern civilization, cursing it and damning it.5

This is not a Luddite tantrum. It is an elegy and a summons. Science and industry, when they dethrone the moral imagination and the sacramental life, become opiates. They substitute measurable progress for spiritual growth. They render the tragic — the great, agonizing, formative confrontations with finitude and guilt — into an avoidable accident of design. The tragic position, which Unamuno champions, is precisely the posture the Machine cannot tolerate: to accept suffering as a schoolroom of the soul, to prefer depth to amenity, to embrace an existential grief that refines rather than numbs.

5. Disease, Progress, and the Perverse Logic of Solving

We must not sentimentalize disease; yet neither may we pretend that every problem’s solution is a proper aim. Unamuno again:

[D]isease itself is the essential condition of what we call progress, and progress itself a disease.6

The paradox is blisteringly simple: what we call progress is often the domestication of the problematic into the manageable — and when every problem is solved, life flattens into a surface without longing. The Machine prides itself on solving; God sometimes calls us to kneel instead. In the Christian register, sickness is not merely to be eradicated but to be understood as occasion for compassion, dependence, and an encounter with the limit. The Machine has little patience for limits; its religion is omnipotence. Beware the theology of the omnipotent tool.

6. The Vital Principle: Life’s Insistence Against Assimilation

Unamuno’s insistence on the vitality of the living resists assimilation into the dead economy of utility:

The vital principal asserts itself, and, in asserting itself creates, making use of its enemy rationality, a whole edifice of dogma, and the Church defends it against rationalism, against Protestantism, against Modernism. The Church is defending life. It stood up against Galileo, and it did right, for his discovery, at its inception and until it became assimilated to the economy of human though, tended to shatter the anthropomorphic belief that the universe was created for man. The Church opposed Darwin, and it did right, for Darwinism tends to shatter our belief that man is an exceptional animal expressly created to be made eternal, Lastly, Pius IX, the first pontiff to be declared infallible, declared himself irreconcilable with modern civilization so-called. And he did right.7

Life asserts. It will not be wholly transliterated into metrics. This is Lawrence’s cry as well: the body and the soil and the immediate token of sensation refuse to be normalized into data. The Machine, in its sameness, is the force that would convert the living into records and reduce the sacrament into an API call. Resist this. Defend the claims of the vital against the administrative.

7. The River and the Madness of Reversal

There are those who say, in technical tones, that we can reroute the river of history; Unamuno speaks to this hubris with tenderness and fury:

I know it is madness to try to drive the waters of a river back to their source, and that it is only the populace who rummages in the past for a cure to its ills. But I also know that whoever does battle for any ideal whatsoever, though the ideal seem to belong to the past, is a person who drives the world on into the future, and that the only reactionaries are those who find themselves at ease in the present. Any presumed restoration of the past is a pre-creation of the future, and if the past is a dream, something imperfectly known, so much the better. Inasmuch as we necessarily march into the future, whoever walks at all is walking into the future even if he walks backwards. And who is to say that this is not the better way to walk?8

To attempt to drive the river back is the Machine’s most telling fantasy: the fantasy that we may control the currents of desire, grief, and death with appliances and software. The Christian existential response is chastened: do not attempt to reverse what is ordained by finitude; rather, learn the art of passage. The river will force you either to drown or to learn to swim in a new humility. The Machine promises dry land by means of suspension bridges; God asks us to learn how to wade, to be cleansed in the current.

8. The Programmer’s Pride and the Hollow Brain

A voice from another quarter — a contemporary plaint — names the metamorphosis that threatens the mind itself:

Man was programmed by God to solve problems, but he has started to create them rather than solve them. The machine was programmed by man to solve the problems that he created. But the machine is actually beginning to create problems that disorient and swallow up man. The machine continues to grow. It’s huge now. To the point where man ceases to be a human organism. And when it comes to the perfection of being created, all that will remain is the machine. God has created a problem for himself. He will eventually destroy the machine and start all over again with ignorant man once more face-to-face with the apple. Otherwise man will merely be a sad ancestor of the machine; far better the mystery of paradise.9

The language is apt: the man who was designed to solve problems risks becoming a problem-solving device. The Christian witness says: the intellect is a servant, not a god. The Machine makes the intellect an idol. We must refuse the blasphemy of turning the given gift of mind into a handmaiden of mechanism. We must re-orient thought to wonder, to ethical responsibility, to the mystery of the neighbor, not to perpetual optimization.

9. The Brain, the Song, and the Mechanical Burst

Finally, imagine the brain “filled to bursting with machines”:

Filled to bursting with machines, will the brain still be able to safeguard the existence of our thin rivulet of dream and escape? Man marches at a sleepwalker’s pace toward murderous mines, led on by the inventor’s song…10

If the brain is so full that it cannot listen to the Creator’s song, then civilization has become a cathedral abandoned by God. We have plenty of instruments that hum, but have we the ears to hear the shepherd’s pipe? The Machine multiplies noise; grace requires silence. The prophet must learn to detect the faint note of lowing in the field of the heart.

10. Lawrencian Flame: Flesh and Earth Against the Circuit

Permit me now to speak in a register that is Lawrencian, because the Lawrencian voice will sharpen the moral imagination into a blade. Lawrence insisted that the body is at once truth and sacrament; that tree worship — the worship of rootedness — bears witness to a religion older and truer than the pulsing neon of the factory. To be Lawrencian is to refuse the abstraction that would substitute manuals for rites, transactions for vows, steam for sacrament. Hear the summons:

Re-embody your reverence. Worship the collarbone and the chest that rises with a child’s breath. Celebrate the hunger that makes saints out of sinners when it is rightly offered.

Re-sanctify work. Let work be not only for wages but for devotion. Let the hands that plant a tree know that they are repeating in dirt what the angels repeat in heaven.

Re-accept fear. Do not flee the trembling; walk into it. Fear turned into faith becomes the door to a reconciled courage.

Reclaim the neighbor. Resist the algorithm that would turn persons into profiles. Call people by name; not id numbers.

Re-enter the terrible joy of limitation. Embrace the Cross as the form through which the highest possibility of life is attained: one who gives up control discovers mercy.

11. Christian Existentialism: Suffering, Freedom, and the Work of Redemption

To be Christian and existential is to accept an austere dialectic: God calls us into freedom, and freedom makes us responsible for the abyss. Technology offers us the seduction of diminished responsibility: systems that decide, smart processes that alleviate guilt, bureaucracies that bear sins for us. But there is no salvation through delegation. Repentance is personal. Redemption requires the willing admission of guilt and the joyful acceptance of penance that opens the heart to love.

Let us be precise in doctrine and fiery in conviction: grace is not a substitute for courage. Grace does not unburden a person of the duty to choose rightly; it empowers the chooser. The Machine often promises a painless moral life by shifting choices to code. We must refuse this false mercy. We must choose, and in choosing we must be prepared to bear the consequences.

12. Practical Implications — A Liturgy of Resistance

What, then, should we do? Here are practical counsels, austere because truth is austere:

Practice deliberate solitude. Let there be hours unmediated by devices. Let Kierkegaard’s physician examine you. Make room for the kind of silence in which conscience speaks.

Reimagine work as vocation. When you work, ask whether your labor builds the person or the ledger. Choose tasks that shape character, not merely metrics.

Emphasize embodied rituals. Eat with care; touch with reverence; sleep without screens; pray with the dirt under your nails.

Make community real. Resist the temptation to maintain relationships through platforms that shorten attention. Gather in bodies as well as in feeds.

Protect children from early monetized cognition. Teach them wonder before you teach them narratives of productivity.

13. An Exhortation — The Final Word

I end with an exhortation in which all of the above converge: do not trade the altar for the console. Do not let the Machine be your confessor, your spouse, your God. Let the Machine be what it was made to be — a set of instruments, neutral in themselves, dangerous when idolized. Remember the quotations we have heard: the examining physician, the fearful insight of Sancho, the curse against the opiates of civilization, the paradox of disease and progress, the river we cannot reverse, the programming of man, and the brain “filled to bursting.” These are not casual remarks; they are our witnesses. They cry out to us to be small enough to recognize our needs, and large enough to accept the work.

If you would be Christian and Lawrencian and existentially awake, then you must learn to suffer the blow that separates you from the machinic consolation and puts you where grace can find you: in hunger, in shame, in the open field where the raven writes its new gospel in the snow. Stand there and read it.

14. The Account Book of Judgment

On the last page — let there be no mistaking this matter — worth will be counted not in inventions but in fidelity. The ledger that matters is not the balance sheet of output but the record of souls who took responsibility, who refused the anesthetics, who accepted fear as a sacrament, who loved the neighbor more than the network. The Machine will not remember your repentance; God will. Be mindful of this difference.

15. Benediction

May you, who have ears to hear, take these words and let them be a furnace for your interior: burn away the false conveniences; temper your mind in solitude; revive the liturgies of flesh and earth; choose courage in the face of the river; labor with hands that know sacrament; and above all, be a human organism in the presence of God’s mystery.

I will leave the last words to Unamuno, who writes the following:

[Y]ou cannot dominate the world with cannons, submarines, zeppelins, microscopes, telescopes, pharmaceuticals, engineering, and all sorts of sciences and technologies and disciplines that have a cave-like, caveman-like soul and lack a sense of one’s own free personality.

[…]

For my part I do not conceal the fact that I pray for the defeat of technology, and even of science, of any and every ideal which has to do with getting rich, with earthly prosperity, and with territorial or mercantile aggrandizement.

If the war brings down worldly European pride and returns us to some kind of new romantic age, good luck to it! Monotony would have finally done us in, killed us off, in a Europe run by engineers, druggists, professors, scholars, travelling salesmen, soldiers, pedants, monistic philosophers, “singers of life,” apaches, and such truck. And so, what if, as some fear, superstitions thought dead were to be revived?

Better superstition than that awful technological, specialist, and science-ridden Europe of the end of the 19th century.11

Amen.

Lucian Blaga, In Praise of Sleep, trans. Andrei Codrescu (Boston: Black Widow Press, 2019), 141.

Søren Kierkegaard, For Self-Examination and Judge for Yourselves, trans. Walter Lowrie (London: Oxford University Press, 1946), 71–72.

Miguel de Unamuno, Our Lord Don Quixote, trans. Anthony Kerrigan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967), 57–58.

ibid., 218–19.

Miguel de Unamuno, The Private World, trans. Anthony Kerrigan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), 200.

Miguel de Unamuno, The Tragic Sense of Life in Men and Nations, trans. Anthony Kerrigan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), 23.

ibid., 80.

ibid., 348–49.

Clarice Lispector, Too Much of Life, trans. Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson (New York: New Directions, 2022), 307–8.

René Char, Furor and Mystery & Other Writings, trans. Mary Ann Caws and Nancy Kline (Boston: Black Widow Press, 2010), 173–74.

de Unamuno, The Private World, 215–16.

Excellent!

Never mind that it is completely impossible to reject technology.

Perhaps you could begin by turning off your computer. And, even more radical, dis-connecting your home/dwelling from the electrical grid as supplied by your local power/electric company.

In a very real sense electricians, and plumbers too are the most important workers. Turn off the pumps and very soon you may find your bathroom/toilet flooded in excrement.

Bring out the candles! And the matches to light them too.

But where do they come from?

Grow your own food!

Where does the water come from. And what about your sewerage.

All municipal water/sewerage systems depend on a network of electrical pumps.

Every dimension of ones life is now completely dependent/enmeshed/entangled in the technological world.

Where and how does your food end up in your refrigerator - as if by magic. It all depends on a vast world-wide chain/web of supply chains.