Physicality

The Machine Will Never Triumph, part thirty-eight

When I went to the circus—

When I went to the circus that had pitched on the waste lot

it was full of uneasy people

frightened of the bare earth and the temporary canvas

and the smell of horses and other beasts

instead of merely the smell of man.

Monkeys rode rather grey and wizened

on curly plump piebald ponies

and the children uttered a little cry—

and dogs jumped through hoops and turned somersaults

and then the geese scuttled in in a little flock

and round the ring they went to the sound of the whip

then doubled, and back, with a funny up-flutter of wings—

and the children suddenly shouted out.

Then came the hush again, like a hush of fear.

The tight-rope lady, pink and blonde and nude-looking, with a few gold

spangles

footed cautiously out on the rope, turned prettily, spun round

bowed, and lifted her foot in her hand, smiled, swung her parasol

to another balance, tripped round, poised, and slowly sank

her handsome thighs down, down, till she slept her splendid body on the

rope.

When she rose, tilting her parasol, and smiled at the cautious people

they cheered, but nervously.

The trapeze man, slim and beautiful and like a fish in the air

swung great curves through the upper space, and came down

like a star

—And the people applauded, with hollow, frightened applause.

The elephants, huge and grey, loomed their curved bulk through the

dusk

and sat up, taking strange postures, showing the pink soles of their feet

and curling their precious live trunks like ammonites

and moving always with soft slow precision

as when a great ship moves to anchor.

The people watched and wondered, and seemed to resent the mystery

that lies in beasts.

Horses, gay horses, swirling round and plaiting

in a long line, their heads laid over each other’s necks;

they were happy, they enjoyed it;

all the creatures seemed to enjoy the game

in the circus, with their circus people.

But the audience, compelled to wonder

compelled to admire the bright rhythms of moving bodies

compelled to see the delicate skill of flickering human bodies

flesh flamey and a little heroic, even in a tumbling clown,

they were not really happy.

There was no gushing response, as there is at the film.

When modern people see the carnal body dauntless and

flickering gay

playing among the elements neatly, beyond competition

and displaying no personality,

modern people are depressed.

Modern people feel themselves at a disadvantage.

They know they have no bodies that could play among the elements.

They have only their personalities, that are best seen flat, on the film,

flat personalities in two dimensions, imponderable and touchless.

And they grudge the circus people the swooping gay weight of limbs

that flower in mere movement,

and they grudge them the immediate, physical understanding they have

with their circus beasts,

and they grudge them their circus-life altogether.

Yet the strange, almost frightened shout of delight that comes now and

then from the children

shows that the children vaguely know how cheated they are of their

birthright

in the bright wild circus flesh.1

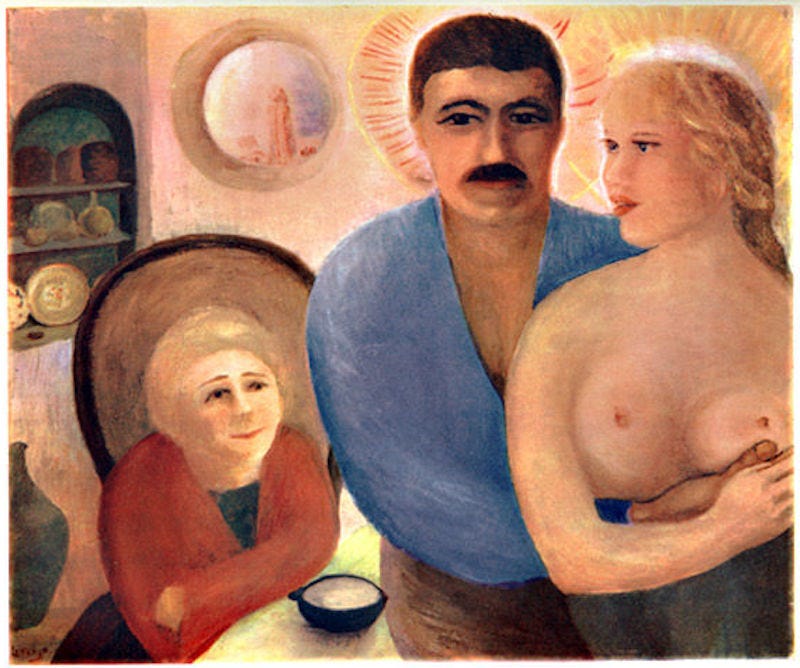

Ancient people knew of no divide between the material and the spiritual. For ancient man, the body was spiritual, and the Gods were embodied. Ancient religion was overwhelmingly body-positive, but modern people have learned to hate the body and to be ashamed of the body. This is a process that started long ago. Almost two-thousand years of misinterpretations of the message of Jesus drove people away from their own bodies, but the Protestant Reformation, followed by the Enlightenment, hastened the process. Still, no amount of Christianity could ever really, fully, alienate man from his own body; that was left to modernity. When you first have simple machines, then computers taking over all the work of man, his body atrophies, and so do vital faculties within his mind. Modern society now hates the sacred body so much it is willing to allow for the possibility of genetic engineering, cloning, microchip implants, and even cybernetic body modifications. Some even go so far as to look forward to a future when they can achieve “immortality” through the uploading of their consciousness to an android, or even buildings full of computers that serve to store data that other computers can access (“the cloud”). The true consciousness can never be uploaded, and whatever functions a mechanical contrivance such an android is able to perform, it will not be alive. How could we come to such a dreadful state? Lawrence has the answer:

What it amounts to, really, is physical repulsion. […] [W]e are all physically repulsive to one another. The great advance in refinement of feeling and squeamish fastidiousness means that we hate the physical existence of anybody and everybody, even ourselves. The amazing move into abstraction on the part of the whole of humanity—the film, the radio, the gramophone—means that we loathe the physical element in our amusements, we don’t want the physical contact, we want to get away from it. We don’t want to look at flesh-and-blood people—we want to watch their shadows on a screen. We don’t want to hear their actual voices: only transmitted through a machine. We must get away from the physical.2

His words ring prophetic, and are truer now than they were when he wrote them. In the two short decades since people started using so-called “smart” phones, the move into abstraction has accelerated at a maddening pace. People today no longer want friends, and some have given up physical love, only to replace these vital relationships with simulacra transmitted through screens. First we lost our connection to trees, then to animals, and now even to other men. To set things right, we must get back into touch with other men, animals, and trees. Lawrence speaks of how a living relationship with horses made people and cities more alive:

Within the last fifty years man has lost the horse. Now man is lost. Man is lost to life and power—an underling and a wastrel. While horses thrashed the streets of London, London lived.

The horse, the horse! the symbol of surging potency and power of movement, of action, in man. The horse, that heroes strode. Even Jesus rode an ass, a mount of humble power. But the horse for true heroes. And different horses for the different powers, for the different heroic flames and impulses.3

Cry of the masses.

Give us back, Oh give us back

Our bodies before we die!

Trot, trot, trot, corpse-body, to work.

Chew, chew, chew, corpse-body, at the meal.

Sit, sit, sit, corpse-body, in the car.

Stare, stare, stare, corpse-body, at the film.

Listen, listen, listen, corpse-body, to the wireless.

Talk, talk, talk, corpse-body, newspaper talk.

Sleep, sleep, sleep, corpse-body, factory-hand sleep.

Die, die, die, corpse-body, doesn’t matter!

Must we die, must we die

bodiless, as we lived?

Corpse-anatomies with ready-made sensations!

Corpse-anatomies, that can work.

Work, work, work,

rattle, rattle, rattle,

sit, sit, sit,

finished, finished, finished—

Ah no, Ah no! before we finally die

or see ourselves as we are, and go mad,

give us back our bodies, for a day, for a single day

to stamp the earth and feel the wind, like wakeful men again.

Oh, even to know the last wild wincing of despair,

aware at last that our manhood is utterly lost,

give us back our bodies for one day.4

When all one does is work at a meaningless, repetitive job, and then amuse himself with television, video games, or drugs, then that person is not really alive. Some ancient and classical thinkers believed that only enlightened souls attain immortality. Whether that is true or not, we cannot answer, but we can say that if one’s entire life is meaningless work, followed by meaningless entertainment, then life doesn’t matter for that person, and neither does death. For death to matter, life must have mattered, and for life to matter, it must be a connected life, not through social networks, but through a vital, living connection to other people, animals, the earth, and, most of all, the Gods. All the computers in the world are nothing compared to the miracle of a single human hand. “[T]he naked human hand with a bit of new soft mud is quicker than time, and defies the centuries.”5

Future Religion

The future of religion is in the mystery of touch.

The mind is touchless, so is the will, so is the spirit.

First comes the death, then the pure aloneness, which is permanent

then the resurrection into touch.6

As Lawrence makes clear, death is not the end. But, he also makes clear that most modern religions have a mistaken eschatology, and that many mystical traditions are wrong as well. The Gods exist, but they exist through embodiment. Even the primordial Fire is tangible, even if in a subtle way. The Greeks knew we would be reborn with bodies, hence the concept of reincarnation. The Catholics (and Orthodox), with the doctrine of the resurrection of the body, also have intuited part of the truth. There is no resurrection of just the mind. There will be a physical resurrection, even if the physical state we will be reborn into is unlike anything we now experience. Mystics of many traditions, despite their good intentions, have played into the hand of modernity’s mind-centrism, through doctrines that speak of only the soul as immortal. The body may die, but every part of a man that is in touch with the Gods is infused with their fire, and on the day that man dies, he will be reborn, not as a senseless, touchless soul, but into a state with a heightened sense of touch. As Lawrence writes: “[O]ne remembers the old dictum, that every part of the body and of the anima shall know religion, and be in touch with the gods.”7

Non-existence

We don’t exist unless we are deeply and sensually in touch

with that which can be touched but not known.8

Conventional wisdom has it that the Divine can be known but not touched. Lawrence reverses this, to state that the Gods can be touched but not known. Lawrence is correct, since knowledge of the Gods would be fleeting and limited, but a deep, sensual touch of the Gods through the reaching out of heart and soul is a true experience of the Divine, albeit one that cannot be put into words. We are not conscious matter that is a result of random animal evolution, but are spiritual beings with roots in the primordial Fire. All of us are born in touch with the Divine, but many choose the paths of money, the ego, and distraction, which cuts us off. Those who are in touch with the Divine are alive in the truest sense of the word, but those who are cut off are the living dead. When the mind triumphs over the soul, the entire individual being becomes cut off from the vitality at the heart of the cosmos. When enough people allow themselves, through distraction from the real, to become separated from Life and Being, they cease to truly exist, and the society they are a part of dies. As Lawrence writes:

The triumph of Mind over the cosmos progresses in small spasms: aeroplanes, radio, motor-traffic. It is high time for the Millennium.

And alas, everything has gone wrong. The destruction of the world seems not very far off, but the happiness of mankind has never been so remote.

Man has made an enormous mistake. Mind is not a Ruler, mind is only an instrument. The natural laws don’t “govern”, they are only, to put it briefly, the more general properties of Matter. It is just a general property of Matter that it occupies space. 4×4=16 is not “reality”: that is to say, it has no existence in itself. It is merely a permanent property of all things, which the mind recognizes as permanent: as sweetness is a property of sugar. Ideas are not Rulers, or creators: they are just the properties or qualities recognised in certain things. The Logos itself is the same: it is the faculty which recognises the abiding property in things, and remembers these properties. God is the same. God as we think him could no more create anything than the Logos could create anything. God as we conceive him is the great know-all and perhaps be-all, but he could never do anything. He is without form or substance, he is Mind; he is the great derivative. God is derived from the cosmos, not the cosmos from him. God is derived from the cosmos as every idea is derived from the cosmos.

The cosmos is not God. God is a conception, and the cosmos is real. The pebble is real, and 4×4=16 is a property of the pebble. Man is real, and Mind is a property of man. The cosmos is certainly conscious, but it is conscious with the consciousness of tigers and kangaroos, fishes, polyps, seaweed, dandelions, lilies, slugs, and men: to say nothing of the consciousness of water, rock, sun and stars. Real consciousness is touch. Thought is getting out of touch.

The crux of the whole problem lies here, in the duality of man’s consciousness. Touch, the being in touch, is the basis of all consciousness, and it is the basis of enduring happiness. Thought is a secondary form of consciousness, Mind is a secondary form of existence, a getting out of touch, a standing clear, in order to come to a better adjustment in touch.

Man, poor man, has to learn to function in these two ways of consciousness. When a man is in touch, he is non-mental, his mind is quiescent, his bodily centres are active. When a man’s mind is active in real mental activity, the bodily centres are quiescent, switched off, the man is out of touch. The animals remain always in touch. And man, poor modern man, with his worship of his own god, which is his own mind glorified, is permanently out of touch. To be always irrevocably in touch is to feel sometimes imprisoned. But to be permanently out of touch is at last excruciatingly painful, it is a state of being nothing, and being nowhere, and at the same time being conscious and capable of extreme discomfort and ennui.

God, what is God? The cosmos is alive, but it is not God. Nevertheless, when we are in touch with it, it gives us life. It is forever the grand voluted reality, Life itself, the great Ruler. We are part of it, when we partake in it. But when we want to dominate it with Mind, then we are enemies of the great Cosmos, and woe betide us. Then indeed the wheeling of the stars becomes the turning of the millstones of God, which grind us exceeding small, before they grant us extinction. We live by the cosmos, as well as in the cosmos. And whoever can come into the closest touch with the cosmos is a bringer of life and a veritable Ruler; but whoever denies the Cosmos and tries to dominate it, by Mind or Spirit or Mechanism, is a death-bringer and a true enemy of man. […]

How they long for the destruction of the cosmos, secretly, these men of mind and spirit! How they work for its domination and final annihilation! But alas, they only succeed in spoiling the earth, spoiling life, and in the end destroying mankind, instead of the cosmos. Man cannot destroy the cosmos: that is obvious. But it is obvious that the cosmos can destroy man. Man must inevitably destroy himself, in conflict with the cosmos. It is perhaps his fate.

Before men had cultivated the Mind, they were not fools.9

Modern man thinks he is his mind. What a fool! No ancient man would identify with his mind. The mind is a tool, just like the hands and feet. Only a crazy person would look at one of his hands and say that the hand is his true self. God as the divine architect is a figment of the human mind. The true Gods are physical, and in sensual touch, not abstractions of the mind. But, the truest God is the primordial Fire at the heart of the cosmos. This Fire feels through us. We are all part of the Fire, and, as such, immortal. The animals don’t need to know this, since they feel it. We stopped feeling the Divine, so we started trying to know it, and we have failed miserably, so we now try to become godlike, and instead end up far lower than monkeys! As Lawrence makes clear, the man who gets into touch with the Cosmos/Fire/Life is suffused with life, and lives forever. On the other hand, one who denies the Gods, refuses to feel and come into touch, and turns everything into a mental abstraction is a denier of life, so Life, in the end, denies that man. Modern man thinks ancient men were naive, but it is modern men who are great fools for turning the world to mechanism. No matter: the mill-wheels of the Gods will grind these robots exceedingly small.

Demiurge.

They say that reality exists only in the spirit

that corporal existence is a kind of death

that pure being is bodiless

that the idea of the form precedes the form substantial.

But what nonsense it is!

as if any Mind could have imagined a lobster

dozing the under-deeps, then reaching out a savage

and iron claw!

Even the mind of God can only imagine

those things that have become themselves:

bodies and presences, here and now, creatures with a foothold

in creation

even if it is only a lobster on tiptoe.10

As Lawrence understands it, mind does not precede form, but it is form that precedes mind. A God did not decide to create the rose, but allowed the rose to come into being through the suffusion of divine love and grace. This is all beautiful, and part of the eternal flux of things. A man is from the Fire, and so long as he is in touch, he will never die; even if one body dies, he will receive another. When people understood this they lived joyful lives. Now modern people deny religion, deny the soul, deny that the body is anything more than the end-product of evolution, and think that even their mind is just a set of electro-chemical reactions. These modern people are the living dead, and it is no wonder that they suffer from severe anxiety and depression. Lawrence saw this over one hundred years ago:

We have almost poisoned the mass of humanity to death with understanding. The period of actual death and race-extermination is not far off. We could have produced the same barrenness and frenzy of nothingness in people, perhaps, by dinning it into them that every man is just a charnel-house skeleton of unclean bones. Our “understanding,” our science and idealism have produced in people the same strange frenzy of self-repulsion as if they saw their own skulls each time they looked in the mirror. A man is a thing of scientific cause-and-effect and biological process, draped in an ideal, is he? No wonder he sees the skeleton grinning through the flesh.11

If modern science and modern ideologies were correct, life would be meaningless. Thankfully, modern science and philosophy couldn’t be more wrong. Remember, when Lawrence speaks of the cosmos, he is not referring to science’s understanding of the universe, but something far deeper, which Klages describes:

The thought Cosmos is a mechanical confusion of things; the living Cosmos, on the other hand, to which our languages can only allude, cannot be conceptually grasped, for it only reveals itself in the instantaneousness flash of its here and now appearance.12

The work of Creation

The mystery of creation is the divine urge of creation,

but it is a great strange urge, it is not a Mind.

Even an artist knows that his work was never in his mind,

he could never have thought it before it happened.

A strange ache possessed him, and he entered the struggle,

and out of the struggle with his material, in the spell of the urge

his work took place, it came to pass, it stood up and saluted his mind.

God is a great urge, wonderful, mysterious, magnificent

but he knows nothing before-hand.

His urge takes shape in flesh, and lo!

it is creation! God looks himself on it in wonder, for the first time.

Lo! there is a creature, formed! How strange!

Let me think about it! Let me form an idea!13

The preceding poem is a great corrective to much orthodox theology. God is far too often portrayed as a giant mind, a great thinker, but that is superimposing human ideas onto the Divine. A God does not ponder and think about what it will create, but it feels it. The cosmos knows itself through all of creation. If it knew it all before, then there would be no point to creation. Both the monists and pluralists are correct: there is one Fire, but there are many souls, all connected to the fire; there is one God, but there are many Gods. As artists, when they are in touch, are working with divine creativity, they create organically from an inner feeling, just like the Gods create. An artist who creates from the mind alone is no artist at all. There is nothing inherently wrong with the mind if it is viewed as a tool, just as a hand or foot is viewed as a tool. But a human is not at root mind, but soul, and more than the sum of its parts. When the mind is allowed to run wild over all the other faculties, tragedies are bound to occur. We are so mind-centric now we no longer even know what real faith is, nor how to feel and experience the Gods, but try to find religious truths through rational propositions. This is the end of man and religion if it is allowed to continue. We must get back into touch with the cosmos, and learn to feel the vital pulse of life flowing through all things. Lawrence writes:

They killed the passion of the body and the bowels and the heart, and ruled all this with the mind. […] They killed the mystery of the shoulders and hands and all the busy magic of making. […] Men neither eat nor drink any more, save with the mind. […] No man has a friend, except his mind has analysed that friend and scattered his parts like a dead Osiris, torn him with the first great wound of friendship in the thigh, and then gashed up his sides. […] No man kneels to his God any more, but he asks himself: What am I kneeling to? No man sings or speaks in his throat, making language and utterance, but he says: Do I hear myself? Mind art thou master of this? No man lifts his hands without saying: Do I lift my hand with my mind? You walk no more on your feet, but go in machines. You weave no more, and spin no more, you sow and you reap no more: always with your minds you guide great machines. […] It is the triumph of Mind over Matter. Your machines and your education are your triumph. You have cast off the flesh, you [have] achieved the disembodied spirit. And your bones are wilting inside you. Wait! Wait! Your day is over.14

Red Geranium and Godly Mignonette

Imagine that any mind ever thought a red geranium!

As if the redness of a red geranium could be anything but a sensual

experience

and as if sensual experience could take place before there

were any senses.

We know that even God could not imagine the redness of a

red geranium

nor the smell of mignonette

when geraniums were not, and mignonette neither.

And even when they were, even God would have to have a nose

to smell at the mignonette.

You can’t imagine the Holy Ghost sniffing at cherry-pie heliotrope.

Or the Most High, during the coal age, cudgelling his mighty brains

even if he had any brains: straining his mighty Mind

to think, among the moss and mud of lizards and mastodons

to think out, in the abstract, when all was twilit green and muddy:

“Now there shall be tum-tiddly-um, and tum-tiddly um,

hey-presto! scarlet geranium!”

We know it couldn’t be done.

But imagine, among the mud and the mastodons

god sighing and yearning with tremendous creative yearning,

in that dark green mess

oh, for some other beauty, some other beauty

that blossomed at last, red geranium, and mignonette.15

We think we are better than the animals because we think more, but it is the animals who are better than us, because they feel more. The Gods think, but they also feel, and as the Gods are in all things, they feel as a flower, and as a bird. Oh, if only we could get back to our old ways and experience once again the creative urge of the Gods, which they experience, but which we can experience too. Every shoemaker in the Middle Ages knew this. There is no reason, other than stubbornness and hubris, why we can’t go back to better ways of living and dying. But this can never happen so long as we are unbelievers. People of all faiths are welcome in Rananim except for atheists, since their entire world-view goes against our vision for the coming world. We need religion, not as something to study, nor as something to prove, but as a vital, living reality that we can feel. We need religion, and to hell with science:

Religion was right and science is wrong. Every individual creature has a soul, a specific individual nature the origin of which cannot be found in any cause-and-effect process whatever. Cause-and-effect will not explain even the individuality of a single dandelion. There is no assignable cause, and no logical reason, for individuality. On the contrary, individuality appears in defiance of all scientific law, in defiance of reason.16

Bodiless God.

Everything that has beauty has a body, and is a body;

everything that has being has being in the flesh;

and dreams are only drawn from the bodies that are.

And God?

Unless God has a body, how can he have a voice

and emotions, and desires, and strength, glory or honour?

For God, even the rarest God, is supposed to love us

and wish us to be this that and the other.

And he is supposed to be mighty and glorious.17

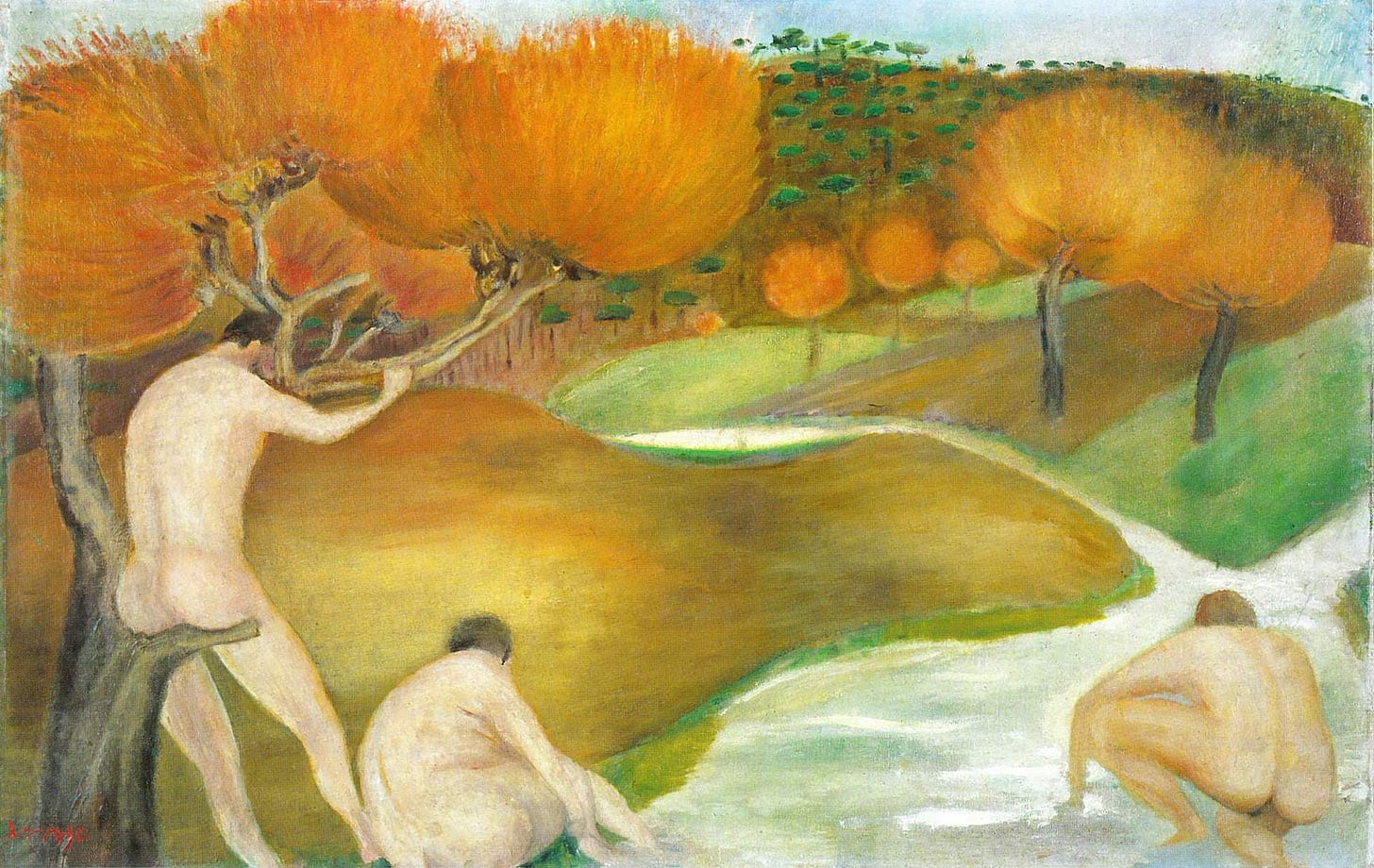

The Gods are embodied. Even the primordial Fire has form. Bodies can change, all is in flux, but that which changes can also stay the same. Just as the man who is eighty is the same person as the child who was five, albeit with more experiences and memories, so the man after he dies and takes on a new form will still be the same man. Men, after they die, live again, and are reborn into another form, but they live, not as some sort of astral projection, but in a real, living form, even if it happens to be a form beyond our comprehension or ability to imagine. And the Gods? The Gods are in the thunder and rain, in the soil and air, in the gentian and rose, in the tiger and lamb, and in man. We are parts of the bodies of the Divine, and are, ourselves divine, so long as we are in touch with that which is greater than we are. We must live fully, here and now! We will have other experiences in other lifetimes, but here, now, in this time and place, and this human body we have marvelous things that we can experience, and it behoves us to experience them fully and without delay. Lawrence passionately pleads with us to make a change in our lives:

What man most passionately wants is his living wholeness and his living unison, not his own isolate salvation of his “soul”. Man wants his physical fulfilment first and foremost, since now, once and once only, he is in the flesh and potent. For man, the vast marvel is to be alive. For man, as for flower and beast and bird, the supreme triumph is to be most vividly, most perfectly alive. Whatever the unborn and the dead may know, they cannot know the beauty, the marvel of being alive in the flesh. The dead may look after the afterwards. But the magnificent here and now of life in the flesh is ours, and ours alone, and ours only for a time. We ought to dance with rapture that we should be alive and in the flesh, and part of the living, incarnate cosmos. I am part of the sun as my eye is part of me. That I am part of the earth my feet know perfectly, and my blood is part of the sea. My soul knows that I am part of the human race, my soul is an organic part of the great human soul, as my spirit is part of my nation. In my own very self, I am part of my family. There is nothing of me that is alone and absolute except my mind, and we shall find that the mind has no existence by itself, it is only the glitter of the sun on the surface of the waters.

So that my individualism is really an illusion. I am a part of the great whole, and I can never escape. But I can deny my connections, break them, and become a fragment. Then I am wretched.

What we want is to destroy our false, inorganic connections, especially those related to money, and re-establish the living organic connections, with the cosmos, the sun and earth, with mankind and nation and family. Start with the sun, and the rest will slowly, slowly happen.18

All of this may sound strange and difficult, but Lawrence gives us good starting points: give up attachments to money and things, and start to love the sun. One who cannot feel the sun, vitally, cannot re-establish other connections, so we must learn to get back into touch with the sun first, and then, as Lawrence says “the rest will slowly, slowly happen.”

Bibliography

Klages, Ludwig. Cosmogonic Reflections. Translated by Joseph D. Pryce. London: Arktos, 2015.

Lawrence, D. H. Apocalypse. Edited by Mara Kalnins. London: Penguin Books, 1995.

———. Late Essays and Articles. Edited by James T. Boulton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

———. Mornings in Mexico and Other Essays. Edited by Virginia Crosswhite Hyde. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

———. Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious. Edited by Bruce Steele. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

———. Quetzalcoatl. Edited by Lois L. Martz. New York: New Directions, 1998.

———. Sketches of Etruscan Places and Other Italian Essays. Edited by Simonetta De Filippis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

———. The Poems. Edited by Christopher Pollnitz. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

D. H. Lawrence, The Poems, ed. Christopher Pollnitz, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 385–87.

D. H. Lawrence, Late Essays and Articles, ed. James T. Boulton (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 283.

D. H. Lawrence, Apocalypse, ed. Mara Kalnins (London: Penguin Books, 1995), 101–2.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:511–12.

D. H. Lawrence, Mornings in Mexico and Other Essays, ed. Virginia Crosswhite Hyde (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 71.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:526.

D. H. Lawrence, Sketches of Etruscan Places and Other Italian Essays, ed. Simonetta De Filippis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 50.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:528.

Lawrence, Apocalypse, 199–200.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:603.

D. H. Lawrence, Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 141.

Ludwig Klages, Cosmogonic Reflections, trans. Joseph D. Pryce (London: Arktos, 2015), 102.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:603–4.

D. H. Lawrence, Quetzalcoatl, ed. Lois L. Martz (New York: New Directions, 1998), 303–4.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:604.

Lawrence, Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious, 17.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:605.

Lawrence, Apocalypse, 149.