Introduction

The Machine Will Never Triumph, part one

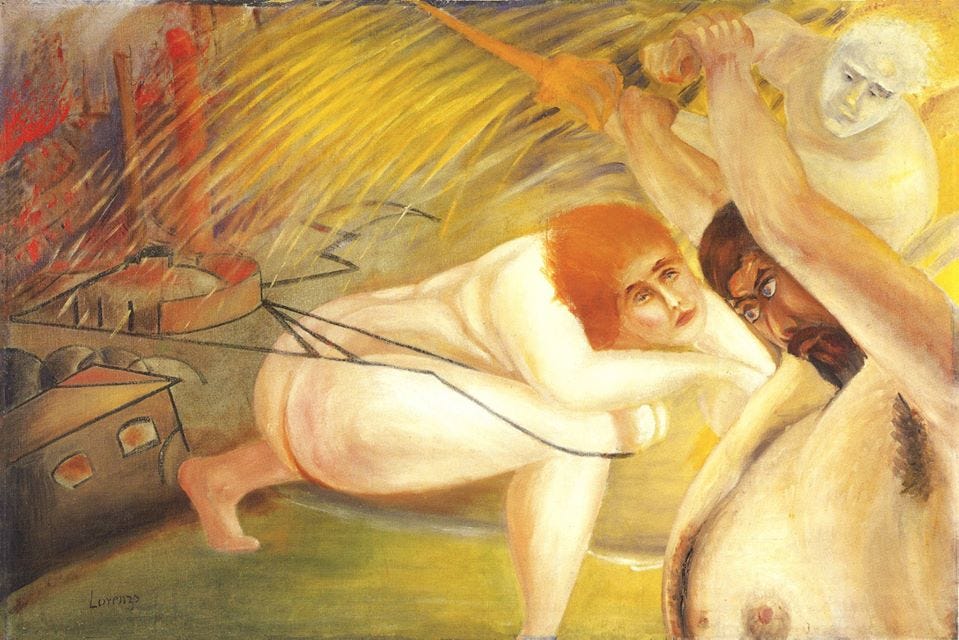

The book you are about to read is not a standard, dry academic tome on D. H. Lawrence. It is not just a tract against technology, although it is that in part, but is meant to be a guide to living one’s life in the modern world, despite all its vicissitudes. The modern world is a hell, and this text will first take us through inferno so as to demolish the metaphysical essence of modernity. We will then proceed through the long purgatorio of change, and will finally, Gods willing, arrive in paradiso, a new world free from the chains of modern technology. There are many critics of the modern, technological world-view, and some of them will be introduced here, but this book is based on the writings and life of David Herbert Lawrence, who didn’t just write against technology, but lived in accordance with his principles. Lawrence demolished the ontological structures of the systems that chain us, but he also created a doctrine that is life-affirming and vivifying. Rather than tackling the problems of our age on their own terms—through analysis, statistics, and data—we aim for a qualitative criticism of technology that goes straight to the heart. Our aesthetic criticism of technology is timeless and we hope will appeal to all those life-loving people who can still marvel in wonder at birds, beasts and flowers. As such, this work is both poetic and religious.

All poetry is religious in its movement, let its teaching be what it may. And we can just as safely say, that no religion is truly religious, a binding back and a connection into a wholeness, unless it is poetic, for poetry is in itself the movement of vivid association which is the movement of religion. The only difference between poetry and religion is that the one has a specific goal or centre to which all things are to be related, namely God; whereas poetry does the magical linking-up without any specific goal or end. Sufficient that the new relations spring up, as it were, that the new connections are made.1

The severing of poetry from religion and religion from poetry has had an effect as damaging as the severing of literature from philosophy and philosophy from literature. If we are to have any hope of creating a better future for ourselves, and all life on this planet, then we must look to poetry, and we must look to religion, which are the twin pillars of any solid, life-affirming education. Each section of this book starts with one of Lawrence’s poems, which are then elucidated upon largely through Lawrence’s own words, drawn from the entire corpus of his prose writings. Where additional detail is needed, further explanations are provided by like-minded poets, thinkers, philosophers, and this author. In a certain sense, this book could be considered a Lawrencian sourcebook; in another sense, it could be considered a hagiography of Lawrence (The Gospel of Lorenzo); in reality it is all of these things: a criticism of technology, a philosophy of life, a hagiography of Lawrence, and a roadmap toward a better world. Rather than write the narrative in a linear manner, the text will proceed in a circular manner, incorporating repetition at varying intervals, and proceeding from an exoteric criticism of the modern world to an esoteric meaning of life and death. While we won’t proceed by any strict mathematical system, our hope is to take one from the outer edges of reality to the kernel at the center of the soul by organizing the sections of the book according to the golden ratio.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.2

This poem of Yeats’ perfectly describes the path from antiquity to modernity, and we aim to reverse that by turning and turning in a narrowing gyre. Clearly, we cannot go back to the past, and any attempt to do so mechanically would be a disaster, but we can proceed forward, into the future, using the example of the past as a bright and shining beacon to guide our way. Yes, we must smash the machines, but we must also rediscover our inner being and foster beauty in this world. The machines are not evil in and of themselves, for they are nothing, a nullity, but they are evil because they are the embodiment of ugliness. Everything today is ugly, and this book aims to be one small effort to reinvigorate the world with truth, beauty, and goodness.

Ultimately, this book will just be a finger pointing at the moon, but if some readers actually look up at the moon and marvel at her beauty with the wonder of childhood, its purpose will have been fulfilled. There is, however, no substitute for the reading of Lawrence’s works—all of them—for there is not a single word written or uttered by the man that is not pregnant with meaning. Consider the following:

Once a book is fathomed, once it is known, and its meaning is fixed or established, it is dead. A book only lives while it has power to move us, and move us differently; so long as we find it different every time we read it. Owing to the flood of shallow books which really are exhausted in one reading, the modern mind tends to think every book is the same, finished in one reading. But it is not so. And gradually the modern mind will realise it again. The real joy of a book lies in reading it over and over again, and always finding it different, coming upon another meaning, another level of meaning. It is, as usual, a question of values: we are so overwhelmed with quantities of books, that we hardly realise any more that a book can be valuable, valuable like a jewel, or a lovely picture, into which you can look deeper and deeper and get a more profound experience every time. It is far, far better to read one book six times, at intervals, than to read six several books. Because if a certain book can call you to read it six times, it will be a deeper and deeper experience each time, and will enrich the whole soul, emotional and mental. Whereas six books read once only are merely an accumulation of superficial interest, the burdensome accumulation of modern days, quantity without real value.3

All of the books of D. H. Lawrence are worth reading and re-reading. Some of his poems and works such as Apocalypse can be read many times, and yet will disclose deeper meaning each time they are read, so long as the reader is willing and able to open his eyes and his soul to the layers of meaning to be found there. Even as the Gospel of John bears more than one reading, so do the best writings of the man his friends and followers called Lorenzo.

Bibliography

Lawrence, D. H. Apocalypse. Edited by Mara Kalnins. London: Penguin Books, 1995.

Yeats, W. B. The Poems. Edited by Daniel Albright. London: Everyman’s Library, 1992.

D. H. Lawrence, Apocalypse, ed. Mara Kalnins (London: Penguin Books, 1995), 190.

W. B. Yeats, The Poems, ed. Daniel Albright (London: Everyman’s Library, 1992), 235.

Lawrence, Apocalypse, 60.

Dear Farasha Euker,

So happy to have discovered your substack while strolling on Paul Kingsnorth's Abbey...

I've read the entire thread you started on the topic of `Orthodox authors who seriously criticize technology` - I have the same question (and the same feeling of disappointment) being an born-orthodox who had to find answers to the technological question only in non-ortodox brilliant authors. I've noticed that you mention some critique made by fr. Alexander Schmemann - in which book can this be found (besides `For the Life of the World`?). Also, you suggest that Frithjof Schuon has written more extensively on modern technology - in which one of his works should I fetch this?

Thank you so much and keep up the good work!

PS - (sorry for making this comment here, I'm quite new to substack and I didn't figure out how to directly message the author - if it's unappropriate, please delete it)

"Everything today is ugly, and this book aims to be one small effort to reinvigorate the world with truth, beauty, and goodness."

Sounds great! Although for me I would say *most* things *human made* are ugly. Still much beauty in our dying natural world, I think.