God and the Gods

The Machine Will Never Triumph, part fifty-two

I remember an afternoon during my journey in Aegina. Suddenly I saw a single bolt of lightning, after which no more followed. My thought was: Zeus.1

1.1. God

Where sanity is

there God is.

And the sane can still recognise sanity

so they can still recognise God.2

The modern world is verging on the insane, yet the most insane thing of all—within the modern world—is the lack of a belief in the Real. Even a slightly sane person must accept the reality of the Divine. As Malcolm de Chazal writes: “Color can’t resist light any more than an object can keep light from reflecting it. We can plug up our eyes and refuse to see God but we can’t turn our backs on Him.”3 Anything true, good, sane, or beautiful is from the Divine. And so, the Gods show themselves where things are sane, such as within old growth forests, and, as Lawrence stated, the people who have not yet become insane robots can recognize the Gods in those places. Without God or the Gods, man is destined to become insane, but within an already insane world, people stop believing in the Divine, which leads to a vicious circle of insanity and irreligiosity. As Lawrence writes, man must have a connection to the transcendental realms to be man:

Yet the human heart must have an absolute. It is one of the conditions of being human. The only thing is the God who is the source of all passion. Once go down before the God-passion and human passions take their right rhythm. But human love without the God-passion always kills the thing it loves. Man and woman virtually are killing each other with the love-will now. What would it be when mates, or comrades, broke down in their absolute love and trust? Because, without the polarised God-passion to hold them stable at the centre, break down they would. With no deep God who is source of all passion and life to hold them separate and yet sustained in accord, the loving comrades would smash one another, and smash all love, all feeling as well. It would be a rare gruesome sight.

Any more love is a hopeless thing, till we have found again, each of us for himself, the great dark God who alone will sustain us in our loving one another. Till then, best not play with more fire.4

Without a connection to the Absolute, life is no longer life. A body without a soul, unconnected to the primordial Fire, is just matter. It is our connection to the life-force pulsating through the cosmos that makes us alive. And that life-force has many manifestations, many of which are immortal, great, and conscious, and those are the Gods. As for an atheist doing anything, they had better stop right now and focus on finding a God, since that is the sole source of meaning. Even those who profess faith, must come into a vivid, vital relationship with the dark God which is both beyond manifestation, and infinitely manifested. So, we all must find the Divine, but how do we go about doing that? Orthodox religion is one answer, but much of orthodox religion has become debased and corrupted. The Gods are not static, and as the thousand-year-old faiths moved away from their Gods, the Gods were moving away from them. If we are going to find a God, we need to engage in a bit of an Easter egg hunt, but the marvelous thing is that we don’t have to search far, since there are Gods right here, right now, within all of us. To know oneself is to come into connection with the Divine. As Lawrence writes:

The Great God has been treated to so many sighs, supplications, prayers, tears and yearnings that, for the time, He’s had enough. There is, I believe, a great strike on in heaven. The Almighty has vacated the throne, abdicated, climbed down. It’s no good your looking up into the sky. It’s empty. Where the Most High used to sit listening to woes, supplications and repentances, there’s nothing but a great gap in the empyrean. You can still go on praying to that gap, if you like. The Most High has gone out.

He has climbed down. He has just calmly stepped down the ladder of the angels, and is standing behind you. You can go on gazing and yearning up the shaft of hollow heaven if you like. The Most High just stands behind you, grinning to Himself.

Now this isn’t a deliberate piece of blasphemy. It’s just one way of stating an everlasting truth: or pair of truths. First, there is always the Great God. Second, as regards man, He shifts His position in the cosmos. The Great God departs from the heaven where man has located Him, and plumps His throne down somewhere else. Man, being an ass, keeps going to the same door to beg for his carrot, even when the Master has gone away to another house. The ass keeps on going to the same spring, to drink, even when the spring has dried up, and there’s nothing but clay and hoof-marks. It doesn’t occur to him to look round, to see where the water has broken out afresh, somewhere else, out of some live rock. Habit! God has become a human habit, and Man expects the Almighty habitually to lend Himself to it. Whereas the Almighty—it’s one of His characteristics—won’t. He makes a move, and laughs when Man goes on praying to the gap in the Cosmos.

“Oh, little hole in the wall! Oh, little gap, holy little gap!” as the Russian peasants are supposed to have prayed, making a deity of the hole in the wall.

Which makes me laugh. And nobody will persuade me that the Lord Almighty doesn’t roar with laughter, seeing all the Christians still rolling their imploring eyes to the skies where the hole is, which the Great God left when He picked up his throne and walked.

I tell you, it isn’t blasphemy. Ask any philosopher or theologian, and he’ll tell you that the real problem for humanity isn’t whether God exists or not. God always is, and we all know it. But the problem is, how to get at Him. That is the greatest problem ever set to our habit-making humanity. The theologians try to find out: How shall man put himself into relation to God, into a living relation? Which is, How shall Man find God?—That’s the real problem.

Because God doesn’t just sit still somewhere in the Cosmos. Why should He? He too wanders His own strange way down the avenues of time, across the intricacies of space. Just as the heavens shift. Just as the pole of heaven shifts. […] Where is He now? Where is the Great God now? Where has He put His throne?

We have lost Him! We have lost the Great God! Oh God, Oh God, we have lost our Great God!5

We have lost our connection to the Divine, and that is the tragedy of our epoch. Re-establishing the connection is of vital importance, and Lawrence’s writings from the time of The Rainbow onwards, are a map to achieving just this on both a personal and societal level.

1.2. All-knowing

All that we know is nothing, we are merely crammed waste-paper baskets

unless we are in touch with that which laughs at all our knowing.6

One may be a genius, have multiple doctoral degrees, and be an expert in all sorts of sciences, but none of that matters unless that person is in touch with one of the Gods. Knowing, in the sense of knowing oneself, the Gods, or a forest (in a vivid, direct, intuitional manner), is a good thing, but knowing in the sense of an accumulation of large amounts of facts and figures is pointless without having a connection to the Divine. One must be in touch. Lawrence was in touch, and the following is his creed:

I am a moral animal. But I am not a moral machine. I don’t work with a little set of handles or levers. The Temperance-silence-order-resolution-frugality-industry-sincerity-justice-moderation-cleanliness-tranquillity-chastity-humility keyboard is not going to get me going. I’m really not just an automatic piano[.]

Here’s my creed[…] This is what I believe.

“That I am I.”

“That my soul is a dark forest.”

“That my known self will never be more than a little clearing in the forest.”

“That gods, strange gods come forth from the forest into the clearing of my known self, and then go back.”

“That I must have the courage to let them come and go.”

“That I will never let mankind put anything over me, but that I will try always to recognise and submit to the gods in me and the gods in other men and women.”

There is my creed. He who runs may read. He who prefers to crawl, or to go by gasoline, can call it rot.7

We modern people put up walls to block ourselves from witnessing the ever-present reality of the Gods. We need to tear down those walls and allow ourselves to experience all of the Gods as they enter and leave one’s soul. And since others are also connected to the Divine, and all living things pulse with the divine Fire, a man must treat all that is, all that lives, as an extension of himself. Just this, just this simple rule would blot out all possibility of our vast, perverse machine civilization. No man who sees God in all things could ever allow for the clearing of a forest to build a factory, nor for the clearing of the interior forest in the name of things such as respectability or employability.

1.3. The Mills of God.

Why seek to alter people, why not leave them alone?

The mills of God will grind them small, anyhow, there is no escape.

The heavens are the nether mill-stone and our heavy earth

rolls round and round, grinding exceeding small.8

We can, and should, try to heal the world, but there is no use in trying to change people. There is only one person you can change, and that is yourself. If you change yourself, come into touch with the cosmos, join Rananim, and either become a sun-man, or pledge allegiance to a sun-man, you may very well change people through your shining example, but your goal was never changing people, but a communion with the Divine. As for those robots who will never change, no matter; for, as Lawrence stated, they will be ground exceedingly small between the millstones of the Gods and the earth.

Now as for the Gods: the Gods are the Gods, and men are men, but men, in their foolishness, have tried to domesticate the Gods. The Gods cannot be domesticated like some pet, or a human-machine. No! The Gods, all of them, from the monolithic Hebrew God to the tribal Gods of cannibalism, are wild and savage. The Gods don’t care about our family picnics, and football games; they want the sacrifice of our egos; they want us to murder our lower selves at their altars; they want us to stand naked before them at sunrise on the top of a mountain peak, in the midst of storm-force gales. The Gods of ancient mythology, and the Gods that are revealed in sacred scriptures, such as the Bible—particularly parts of the Old Testament and the Book of Revelation—are fierce, ferocious, and dark. The pagans knew the true nature of the Gods. The early Muslims realized that God was becoming too domesticated, so they forbid His representation, so that he would remain dark, powerful, and mysterious. The true Muslim God is a dark God: savage, wild, and violent, as He should be. Even Jesus, portrayed by so many as a prophet of universal love, was proved by G. K. Chesterton to be a wild God, a fighter, a revolutionary. As Lawrence declared: “The gods who had demanded human sacrifice were quite right, immutably right. The fierce, savage gods who dipped their lips in blood, these were the true gods.”9 All the great Gods shun not only the atheists of today, but also the vast hordes of domesticated pigs whose religion is false. As Lawrence writes, with such starkly poetic vividness:

What God can it be that likes success and Sunday dinners? Oh, God! It must be a big, fat, reesty sort of God.

“My God is dark and you can’t see him. You can’t even see his eyes, they are so dark. But he sits and bides his time and smiles, in the spaces between the stars. And he doesn’t know himself what he thinks. But there’s deep, powerful feelings inside him, and he’s only waiting his time to upset this pigsty full of white fat pigs. I like my Lord. I like his dark face, that I can’t see, and his dark eyes, that are so dark you can’t see them, and his dark hair, that is blacker than the night, on his forehead, and the dark feelings he has, which nobody will ever be able to explain. I like my Lord, my own Lord, who is not Lord of pigs.”10

1.4. Absolute Reverence.

I feel absolute reverence to nobody and to nothing human

neither to persons nor things nor ideas, ideals nor religions nor

institutions,

to these things I feel only respect, and a tinge of reverence when I see the

fluttering of pure life in them.

But to something unseen, unknown, creative

from which I feel I am a derivative

I feel absolute reverence. Say no more!11

How should a person be in the world? Simple: a person should have no attachments to any man-made, artificial objects, systems, institutions, nations, etc. One may feel a sense of awe at a hand-made work of art, or feel love for all of creation that contains some of the divine Fire, but the only Reality before which we should prostrate ourselves with absolute devotion, is the dark inscrutable, indescribable Absolute, in all its manifestations. One can find the Gods through wild nature, or even through devoted, fiery humans, but in this day and age of extreme human hubris, it is time to set aside the merely human to focus on the Divine. As Lawrence writes:

It is time for us now to look all around, round the whole ring of the horizon—not just out of a room with a view; it is time to gather again a conception of the Whole: as Plato tried to do, and as the mediaeval men—as Fra Angelico—a conception of the beginning and the end, of heaven and hell, of good and evil flowing from God through humanity as through a filter, and returning back to god as angels and demons.

We are tired of contemplating this one phase of the history of creation, which we call humanity. We are tired of measuring everything by the human standard.12

The Gods are Gods not only of love, but of power.13 But, this power is true power. What we call power today is the false power of human hubris. True power only comes from the Gods, and ultimately from the Fire. The false idea of power started centuries ago with magicians who felt they could do the work of the Gods. This is why all true religions were against most forms of magic; and many forms of magic ultimately led to what I am calling “the Machine,” which stands for the mechanized and atheistic mindset of the modern world. True power, true magic is not generated by man, but is a form of theurgy in which a sun-man comes into touch with the Divine and channels its power. The power of the Gods manifests in the hurricanes and earthquakes that wipe out cities. Eventually, the Gods through storms and deadly heat waves, prompted by human activities altering the climate, may eventually grind up and burn down the entire modern edifice.14 One is either close to the Fire or far away, and the fiery men are the great ones, but the cold and robotic masses are fallen creatures. Lawrence writes of this as follows:

Myself I want Power. But I don’t want to boss anybody.

I want Honour. But I don’t see any existing nation or government that could give it [to] me.

I want Glory. But heaven save me from mankind.

I want Might. But perhaps I’ve got it.

The first thing, of course, is to open one’s heart to the source of Power, and Might, and Glory, and Honour. It just depends, which gates of one’s heart one opens. You can open the humble gate, or the proud gate. Or you can open both, and see what comes.

Best open both, and take the responsibility. But set a guard at each gate, to keep out the liars, the snivellers, the mongrel and the greedy.

However smart we be, however rich and clever or loving or charitable or spiritual or impeccable, it doesn’t help us at all. The real power comes in to us from beyond. Life enters us from behind, where we are sightless, and from below, where we do not understand.

And unless we yield to the beyond, and take our power and might and honour and glory from the unseen, from the unknown, we shall continue empty. We may have length of days. But an empty tin can lasts longer than Alexander lived.

So, anomalous as it may sound, if we want power, we must put aside our own will, and our own conceit, and accept power, from the beyond.

And having admitted the power from the beyond into us, we must abide by it, and not traduce it. Courage, discipline, inward isolation, these are the conditions upon which power will abide in us.

And between brave people there will be the communion of power, prior to the communion of love. The communion of power does not exclude the communion of love. It includes it. The communion of love is only a part of the greater communion of power.

Power is the supreme quality of God and man: the power to cause, the power to create, the power to make, the power to do, the power to destroy. And then, between those things which are created or made, love is the supreme binding relationship. And between those who, with a single impulse, set out passionately to destroy what must be destroyed, joy flies like electric sparks, within the communion of power.

Love is simply and purely a relationship, and in a pure relationship there can be nothing but equality; or at least equipoise.

But Power is more than a relationship. It is like electricity, it has different degrees. Men are powerful or powerless, more or less: we know not how or why. But it is so. And the communion of power will always be a communion in inequality.

In the end, as in the beginning, it is always Power that rules the world! There must be rule. And only Power can rule. Love cannot, should not, does not seek to. The statement that love rules the camp, the court, the grove, is a lie; and the fact that such love has to rhyme with “grove”, proves it. Power rules and will always rule. Because it was Power that created us all. The act of love itself is an act of power, original as original sin. The power is given us.

As soon as there is an act, even in love, it is power. Love itself is purely a relationship.

But in an age that, like ours, has lost the mystery of power, and the reverence for power, a false power is substituted: the power of money. This is a power based on the force of human envy and greed, nothing more. So nations naturally become more envious and greedy every day. While individuals ooze away in a cowardice that they call love. They call it love, and peace, and charity, and benevolence, when it is mere cowardice. Collectively they are hideously greedy and envious.

True power, as distinct from the spurious power, which is merely the force of certain human vices directed and intensified by the human will: true power never belongs to us. It is given us, from the beyond.

Even the simplest form of power, physical strength, is not our own, to do as we like with. As Samson found.

But power is given differently, in varying degrees and varying kind to different people. It always was so, it always will be so. There will never be equality in power. There will always be unending inequality.

Nowadays, when the only power is the power of human greed and envy, the greatest men in the world are men like Mr Ford, who can satisfy the modern lust, we can call it nothing else, for owning a motor-car: or men like the great financiers, who can soar on wings of greed to uncanny heights, and even can spiritualise greed.

They talk about “equal opportunity”: but it is bunk, ridiculous bunk. It is the old fable of the fox asking the stork to dinner. All the food is to be served in a shallow dish, leveled to perfect equality, and you get what you can.

If you’re a fox, like the born financier, you get a bellyful and more. If you’re a stork, or a flamingo, or even a man, you have the food gobbled from under your nose, and you go comparatively empty.

Is the fox, then, or the financier, the highest animal in creation? Bah!

Humanity never bunked itself so thoroughly as with the bunk of equality, even qualified down to “equal opportunity”.

In living life, we are all born with different powers, and different degrees of power: some higher, some lower. The only thing to do is honourably to accept it, and to live in the communion of power. Is it not better to serve a man in whom power lives, than to clamour for equality with Mr Motor-car Ford, or Mr Shady Stinnes15? Pfui! to your equality with such men! It gives me gooseflesh.

How much better it must have been, to be a colonel under Napoleon, than to be a Marshal Foch! Oh! how much better it must have been, to live in terror of Peter the Great—who was great—than to be a member of the proletariat under Comrade Lenin: or even to be Comrade Lenin: though even he was greatish, far greater than any extant millionaire.

Power is beyond us. Either it is given us from the unknown, or we have not got it. And better to touch it in another, than never to know it. Better be a Russian and shoot oneself out of sheer terror of Peter the Great’s displeasure, than to live like a well-to-do American, and never know the mystery of Power at all. Live in blank sterility.

For Power is the first and greatest of all mysteries. It is the mystery that is behind all our being, even behind all our existence. Even the Phallic erection is a first blind movement of power. Love is said to call the power into motion: but it is probably the reverse: that the slumbering power calls love into being.16

1.5. Belief

Forever nameless

Forever unknown

Forever unconceived

Forever unrepresented

yet forever felt in the soul.17

What is the primordial fire? There is much more that cannot be said about it than can be positively stated, but it can be felt. One can talk of all of manifestation, including the Gods. The Gods can be known, personally, and one can form a relationship with them. But, the Fire is beyond this, and so must be spoken of negatively, through the use of apophatic theology. Apophatic theology, the via negativa, is helpful in terms of doctrine, but not in terms of practice. Apophatic theology may act as a ladder, but one eventually needs to get off the ladder. One can never come to an understanding of the Fire intellectually, but only through feeling, intuition, and the creative imagination. As Lawrence wrote, it may never be known, but the Fire is present “forever in the soul.”

The Fire is alive, but is beyond being. The conscious reality, within being, but prior to all other being, that simply is, is the great dark God. The dark God contains within itself all the other Gods and Goddesses. The dark God is the macrocosm, and the dark Gods are the microcosms. There is one, great dark God, but everyone has within himself many dark Gods. Lawrence sets forth his theology of the dark God as follows:

That was now all he wanted: to get clear. Not to save humanity or to help humanity or to have anything to do with humanity. No—no[…] Now, all he wanted was to cut himself clear. To be clear of humanity altogether, to be alone. To be clear of love, and pity, and hate. To be alone from it all. To cut himself finally clear from the last encircling arm of the octopus humanity. To turn to the old dark gods, who had waited so long in the outer dark.

Humanity could do as it liked: he did not care. So long as he could get his own soul clear. For he believed in the inward soul, in the profound unconscious of man. Not an ideal God. The ideal God is a proposition of the mental consciousness, all-too-limitedly human. “No,” he said to himself. “There is God. But forever dark, forever unrealisable: forever and forever. The unutterable name, because it can never have a name. The great living darkness which we represent by the glyph, God.”

There is this ever-present, living darkness inexhaustible and unknowable. It is. And it is all the God and the gods.

And every living human soul is a well-head to this darkness of the living unutterable. Into every living soul wells up the darkness, the unutterable. And then there is travail of the visible with the invisible. Man is in travail with his own soul, while ever his soul lives. Into his unconscious surges a new flood of the God-darkness, the living unutterable. And this unutterable is like a germ, a foetus with which he must travail, bringing it at last into utterance, into action, into being.

But in most people the soul is withered at the source[…] [T]he mass of mankind is soulless. Because to persist in resistance of the sensitive influx of the dark gradually withers the soul, makes it die, and leaves a human idealist and an automaton. Most people are dead, and scurrying and talking in the sleep of death. Life has its automatic side, sometimes in direct conflict with the spontaneous soul. Then there is a fight. And the spontaneous soul must extricate itself from the meshes of the almost automatic white octopus of the human ideal, the octopus of humanity. It must struggle clear, knowing what it is doing: not waste itself in revenge. The revenge is inevitable enough, for each denial of the spontaneous dark soul creates the reflex of its own revenge. But the greatest revenge on the lie is to get clear of the lie.

The long travail. The long gestation of the soul within a man, and the final parturition, the birth of a new way of knowing, a new God-influx. A new idea, true enough. But at the centre, the old anti-idea: the dark, the unutterable God. This time not a God scribbling on tablets of stone or bronze. No everlasting decalogues. No sermons on mounts, either. The dark God, the forever unrevealed. The God who is many gods to many men: all things to all men. The source of passions and strange motives. It is a frightening thought, but very liberating.18

Ultimately, in a man’s life, he must either reject the Gods and turn towards men and motor power, or he must turn away from men and machines, to focus on the Divine. To successfully come into touch with the Real, a man must delve deep within his soul to meet his dark Gods, but he must also come into a living relation with the Gods of life, love, and various forms of manifestation. He may achieve his ultimate consummation by coming into contact with the dark God. This is not the nihilistic unity of the Eastern religions, but is a unity that respects multiplicity. One who is sufficiently prepared will become one with the dark God, yet retain his memories, consciousness, and individuality, just as a man who immerses himself into the sea is still the same man he was on dry land. But, for a man who is unprepared, union with the dark God drowns his soul, and he drinks the waters of Lethe.

We use various terms, such as God, Gods, Divine, Real, Absolute, Fire, etc. both to show very real sides of that which is beyond knowing, but also to show that That Which Is, is beyond the conceptions of a man’s mind. It is with good reason that the Jews forbid the utterance or printing of the divine Name. The dark God cannot be tied down by any name, but various names may help a man in his spiritual practice, and they may lead him towards the Unnameable. This unnameable dark God is what it is, but it is also all the Gods; Semitic, Hellenic, Nordic, and so on. Men and women both must give birth: they must give birth to the divine inner reality of their souls. Our souls contain a germ of the god-stuff, the divine Fire, but it is only a germ, and we must cultivate it throughout our lives. If we do so, we may experience our second birth within this lifetime, escaping from the cycles of birth and death, and ultimately becoming immortal Gods ourselves. This is not Nirvana, which is nihilism by another name. The modern religion that comes closest to understanding this change that comes over a man is Christianity, particularly Orthodox Christianity. A man, when he attains a connection with the dark God, dies in this life and is reborn into eternity. When his physical shell falls away, he is truly reborn with a new body, of subtle spiritualized matter, and his consciousness is in constant contact with the Fountain of all Being. This is the great reward for a sun-man. As for the vast, amorphous hordes of robots, their souls cannot come into contact with the Darkness, so they are reborn, but not resurrected. The resurrected sun-man retains who he was in this life, but the reborn robot is reincarnated with only the barest thread linking it to its previous life. If you get nothing else from this book, please know this: the Machine is a manifestation of the principle of evil. And what are called the dark God, the primordial Fire, and the Holy Spirit, three-in-one, are the great principles of good and life. Fight the Machine, and devote yourself to the Fire. All else is dust.

1.6. Talk of faith.

And people who talk about faith

usually want to force somebody to agree with them,

as if there was safety in numbers, even for faith.19

Some of what we speak of here, some of what Lawrence says, can be disconcerting at first, especially when one realizes that not many others share these views. It may be difficult to accept, but the truth is the truth, and the vast masses of men have been raised in a culture that has largely lost touch with the deeper foundations of reality. Faith is between a man and his God. It matters not whether you join the largest churches or the smallest cults, so long as you cultivate a personal relationship with the Divine, even if you do that completely outside the confines of organized religion. But, man needs fellowship with other men. We must build Rananim so that men of the sun, worshipers of all the Gods, and the dark God can come together in communion. Lawrence describes this need as follows:

[O]ne cannot live a life of entire loneliness, like a monkey on a stick, up and down one’s own obstacle. There’s got to be meeting: even communion. Well then, let us have the other communion.—“This is thy body which I take from thee and eat”—as the priest, also the God, says in the ritual of blood sacrifice. The ritual of supreme responsibility, and offering. Sacrifice to the dark God, and to the men in whom the dark God is manifest. Sacrifice to the strong, not to the weak. In awe, not in dribbling love. The communion in power, the assumption into glory. La gloire.20

As for weaker men who are no longer robots, but who have not yet come into touch with the sun: let them sacrifice to the sun-men who will intercede with the Gods on their behalf.

1.7. Worship.

All men are worshippers

unless they have fallen, and become robots.

All men worship the wonder of life

until they collapse into egoism, the mechanical, self-centred system of the

robot.

But even in pristine men, there is the difference:

some men can see life clean and flickering all around,

and some can only see what they are shown.

Some men look straight into the eyes of the gods

and some men can see no gods, they only know

the gods are there because of the gleam on the faces of the men who see.

Most men, even unfallen, can only live

by the transmitted gleam from the faces of vivider men

who look into the eyes of the gods.

And worship is the joy of the gleam from the eyes of the gods,

and the robot is denial of the same,

even the denial that there is any gleam.21

Religion is not something that is imposed upon man; religion is the natural vocation of man. All early men were religious, and all early men had direct communion with the Divine. But as soon as men started worshiping knowledge… and themselves, they fell, and we are the by-products of that fall. The end-product of the apple is humanity enmeshed in and wholly dependent on technology, what Lawrence (and others) call “the Machine.” And this worship of technology has resulted in modern humanity becoming more robotic. Our only path back to paradise, and the recovery of the old Adam, is through a new form of community that Lawrence called “Rananim,” which will exist largely isolated from the modern world and modern technology, and recreate a sustainable relationship with Nature.

Human civilization must, like the cosmos, be hierarchical. The greatest men are the sun-men, those who experience the presence of the Gods, directly. These men are few and they should rule. Some men hunger for truth and are not fallen robots, but they cannot know the Gods. These men should seek out and rely on such “rightly-guided ones,” for it is under their leadership that they will attain closeness to the Gods. And as for most of the men and women in our times, they have lost so much of their nature as humans, they have become virtually robots, and not even the Gods can save them from the Machine they have become virtually enslaved by. As for this Machine, it is an anti-God, a manifestation of the principle of evil, but unlike the Gnostic evil God, the Machine has no essence of its own, but represents the absence of principle, virtually pure nothingness. As R. S. Thomas writes:

The machine is

our winter, smooth

as ice glassing

over the soul’s surface

We have looked

it in the eye

and seen how our image

gradually is demoted.

Without the tribute

we must bring it

from our dwindling resources

it grows colder and colder.22

Another great Christian thinker, Georges Bernanos, stated that the Machine is “the corporation of corporations, the supreme corporation, the one and only corporation: the divinized technological state, the God of a world without God[.]”23 So robotic men, machines, and technology are the agents through which the Machine,24 the principle of nothingness, operates, in its aim to wipe out all goodness, and all that is, from existence. We could only see the true nature of all of this slowly, but prophets like Lawrence warned us, and we did not heed his call. Now, as Heidegger writes, it may be too late, since “the essence of technology comes to the light of day only slowly. This day is the world’s night, rearranged into merely technological day. This day is the shortest day. It threatens a single endless winter.”25 The only way for man to stem the tide of the Machine is to change the world, but first to change himself, or more accurately, to rediscover who he was all along. Since a man needs both doctrine and practice, Lawrence laid out how his vision of man would act in Rananim:

Temperance: Eat and carouse with Bacchus, or munch dry bread with Jesus, but don’t sit down without one of the gods.

Silence: Be still when you have nothing to say; when genuine passion moves you, say what you’ve got to say, and say it hot.

Order: Know that you are responsible to the gods inside you and to the men in whom the gods are manifest. Recognise your superiors and your inferiors, according to the gods. This is the root of all order.

Resolution: Resolve to abide by your own deepest promptings, and to sacrifice the smaller thing to the greater. Kill when you must, and be killed the same: the must coming from the gods inside you, or from the men in whom you recognise the Holy Ghost.

Frugality: Demand nothing; accept what you see fit. Don’t waste your pride or squander your emotion.

Industry: Lose no time with ideals; serve the Holy Ghost; never serve mankind.26

Sincerity: To be sincere is to remember that I am I; and that the other man is not me.

Justice: The only justice is to follow the sincere intuition of the soul, angry or gentle. Anger is just, and pity is just, but judgment is never just.

Moderation: Beware of absolutes. There are many gods.

Cleanliness: Don’t be too clean. It impoverishes the blood.

Tranquillity: The soul has many motions, many gods come and go. Try and find your deepest issue, in every confusion, and abide by that. Obey the man in whom you recognise the Holy Ghost; command when your honour comes to command.

Chastity: Never “use” venery at all. Follow your passional impulse, if it be answered in the other being; but never have any motive in mind, neither offspring nor health nor even pleasure, nor even service. Only know that “venery” is of the great gods. An offering-up of yourself to the very great gods, the dark ones, and nothing else.

Humility: See all men and women according to the Holy Ghost that is within them. Never yield before the barren.27

These are the thirteen commandments of the Lawrencian religion. There are deeper doctrines and more advanced practices, but these simple, basic rules are the basis for the practice of those who take refuge in Rananim under the guidance and leadership of the rightly guided ones who Lawrence calls “sun-men.” But even before taking refuge in isolated communities of Rananim, you can read them, come to know them, memorize them, and put them into practice, here, now, in your daily life. No one, not even the sun-man, unless he has achieved final consummation with the dark God, is free from struggle. Life is a ceaseless struggle to avoid hubris, egoism, automatism, and mechanism. Vade retro me Machina! (Get thee behind me, O [satanic] Machine!) A man who has perceived reality as Lawrence did, and pledged himself to live the way that Lawrence did, and by extension, with reverence and obedience to requirements of the divine Realities, must always struggle, must always fight against the Machine and its robots. As Lawrence writes:

[B]ecause of the temptation which awaits every individual, the temptation to fall out of being, into automatism and mechanisation, every individual must be ready at all times to defend his own being against the mechanisation and materialism forced upon him by those people who have fallen or departed from being. It is the long unending fight, the fight for the soul’s own freedom, of spontaneous being, against the mechanism and materialism of the fallen.28

1.8. Classes

There are two classes of men:

those that look into the eyes of the gods, and these are few,

and those that look into the eyes of the few other men

to see the gleam of the gods there, reflected in the human eyes.

All other class is artificial.

There is, however, the vast third homogeneous amorphous class of

anarchy

the robots, those who deny the gleam.29

The distinctions between rich and poor, proletarian and bourgeois, capitalist and communist, black and white, are unimportant. There are only two kinds of men who deserve to be called men: those who commune with the Gods, and those who commune with the men who commune with the Gods. The other people on earth who have become virtual robots are not even fit to be called men. And as much as it pains real men to know of fellow human beings who have become like fodder for the Machine, salvation does not come through helping those fallen humans, but through turning-away from them to the Divine. “In some way, humanity dominates your consciousness. So you must hate people and humanity, and you want to escape. But there is only one way of escape: to turn beyond them, to the greater life.”30

1.9. What are the gods?

What are the gods, then, what are the gods!

The gods are nameless and imageless

yet looking in a great full lime-tree of summer

I suddenly saw deep into the eyes of god:

it is enough.31

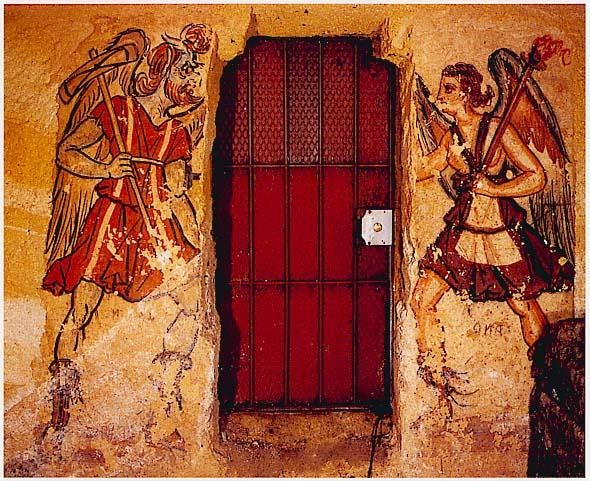

The Gods cannot, adequately, be described. There are manifestations of the Gods, which are real in and of themselves, but compared to the underlying reality, they are symbols pointing to an archetype. Even when all images, names, etc. are let go of, one still tends to have an idea of the Gods, but even this must be let go of. Islam tends to be the religion most vociferously against idol worship, but even the name Allah can be an idol. The Gods cannot be tied down by any name or representation. But, as Lawrence stated above, the Gods are ever-present and all of reality overflows with their being, so one can come into contact—a real, living contact—with the Gods through nature. One can come into contact with the Gods, but as soon as the seeker’s ineffable experience is put into words, the experience is falsified. We can come to know more about the many Gods, but the dark God can never be known, at least not intellectually. It matters not, because the dark God can be felt through the earth, the body of God. All of the cosmos is suffused with the essence of the dark God, the primordial Fire. Lawrence writes of this and other religious intimations he had, in the following passage:

What the dark God is can never be said—Nor, in the knowledge sense, known… I think the earth is alive—I think all the universe is alive… The body is the man—all the rest emanates from the body… the Indian religious dances are the most beautiful and purely religious things I have ever seen—and the so called devil dance in Ceylon is mysterious and lovely, compared to jazz… One must accept change, a great slow change and a slow bitter revocation of what one most dearly is. But one must accept it—or go utterly stale. We are too clever to live…32

All of our cleverness has blinded us to the old realities. The oldest, most obscure religions knew Truth the best. There is one God, the God of Gods, the dark God, and there are many Gods, light and dark Gods of every sort. Beyond even the dark God and beyond being is the primordial, Heraclitean Fire. Now, ask a man to come into touch with the Fire, or even the dark God, and he will laugh in your face. The fact is, not even every sun-man can commune with the dark God. Even the sun-men are often limited to looking into the eyes of the many Gods, or a single one of the many Gods. This is where the error of monotheism came in: Moses was a sun-man, but he only knew one God, and he limited reality to that God. Now, reality, ultimately is one, but it is also many. To say there is one dark God and one Fire is correct, and you can tell that certain Christian and Sufi mystics certainly communed with the dark God, but most Muslims and Christians who speak of God, speak of one God, that is one of the many. Basta! This is all terminology, and the dark God does not desire us to spend our lives on theology, but desires our closeness through touch. This “closeness” comes through the many spirits, daemons, and dark Gods, which enter through our blood and suffuse our bodies with a taste of fire. Lawrence describes this as follows:

The old, dark religions understood. “God enters from below,” said the Egyptians. And that’s right. Why can’t you darken your minds, and know that the great gods pulse in the dark, and enter you as darkness, through the lower gates. Not through the head. Why don’t you seek again the unknown and invisible gods who step sometimes into our great arteries, and down the blood-vessels to the phallos, to the vagina, and have strange meetings there? There are different dark gods, different passions; Hermes Ithyphallos has more than one road. The god of gods is unknowable, unutterable, but all the more terrible; and from the unutterable god step forth the mysteries of our promptings, in different forms: call it Thoth or Hermes, or Bacchus or Horus or Apollo: different promptings, different mysterious forms. But why don’t you leave off your old white festerings in the head, and let the mystery of life come back to you? Why don’t you become silent unto yourselves, and wait and be patient in silence, and let a night fall over your mind and heal you. And then turn again to the dark gods […] and have reverence again, and be grateful for life. […] Why should one be self-conscious and impoverished when one is young and the dark gods are at the gate?33

So, let us leave off thinking too much, and knowing too much. Let us try to start feeling again. For so long man searched for God in heaven, so now he has lost Him completely. It was a great error of Muslims to chastise the idol worshipers. There is a great depth of reality even within a simple stone. As Lawrence writes:

So easy to realise men worshipping stones. It is not the stone. It is the mystery of the powerful, pre-human earth, showing its might. And all, this morning, static, arrested in a cold, milky whiteness, like death, the west lost in the sea.34

1.10. The gods! the gods!

People were bathing and posturing themselves on the beach

and all was dreary, great robot limbs, robot breasts

robot voices, robot even the gay umbrellas.

But a woman, shy and alone, was washing herself under a tap

and the glimmer of the presence of the gods was like lilies,

and like water-lilies.35

Sadly, modern men and women are largely roboticized. Just as animals, mountains, and trees are full of Gods, man used to be full of Gods. But, there are still some people who are free from the stain of the Machine, and these people are a revelation unto themselves. Religion in the ancient, pagan world, was nearly perfect. There is much that is good in Christianity, but much of that is from the pagan heritage. Much of Christianity, today, has degenerated, and sadly become a religion of the Machine, particularly in America. Concerning the most ancient religions compared to Christianity, Lawrence writes:

The religious systems of the pagan world did what Christianity has never tried to do: they gave the true correspondence between the material cosmos and the human soul. The ancient cosmic theories were exact, and apparently perfect. In them science and religion were in accord.36

1.11. Name the gods!

I refuse to name the gods, because they have no name.

I refuse to describe the gods, because they have no form nor shape nor

substance.

—Ah, but the simple ask for images!

Then for a time at least, they must do without.—

But all the time I see the gods:

the man who is moving the tall white corn,

suddenly, it curves, as it yields, the white wheat

and sinks down with a swift rustle, and a strange, falling flatness,

ah! the gods, the swaying body of god!

ah the fallen stillness of god, autumnus, and it is only July

the pale-gold flesh of Priapus dropping asleep.37

There have been many manifestations and representations of the Gods throughout history. Those manifestations and representations are true, but they only contain a limited amount of the truth. The esoteric truth about the Gods is that they have no names, nor forms. They may take names and forms, but those names and forms are not intrinsic to the Gods. Dionysus and Christ are both real, so far as it goes, but their reality goes far beyond their physical manifestations. The holy names and sacred icons can lead one toward the great Gods, but the danger is that it can also lead one away from them. Lawrence was a believer in the reality of all of the manifestations of the dark God, but he also understood that past a certain point names and images cease being helpful, and instead become a hindrance on the path. And what of the man who has passed beyond names and icons, but who has not yet come into a mystical communion with the dark God? He should know that the Gods are all-present, ever-present, and he should develop his third eye so that he can see the Gods everywhere. Lawrence felt the presence of the Gods in everything that lived on the face of the earth. For Lawrence, all that lives is holy. And yet, though the Gods themselves are without names, the names of the Gods are essential parts of one’s spiritual practice. Allah, Jesus, and Hermes may be beyond their names, but the invocation of those names is a ladder of divine ascent for the practitioner; they are seeds that bear beautiful fruit: “Ah, the names of the gods! Don’t you think the names are like seeds, so full of magic, of the unexplored magic?”38

1.12. There are no gods—

There are no gods, and you can please yourself

have a game of tennis, go out in the car, do some shopping, sit and talk,

talk, talk

with a cigarette browning your fingers.

There are no gods, and you can please yourself—

Go and please yourself—

But leave me alone, leave me alone, to myself!

And then in the room, whose is the presence

that makes the air so still and lovely to me?

Who is it that softly touches the sides of my breast

and touches me over the heart

so that my heart beats soothed, soothed, soothed and at peace?

Who is it smooths the bed-sheets like the cool

smooth ocean when the fishes rest on edge

in their own dream?

Who is it that clasps and kneads my naked feet, till they unfold,

till all is well, till all is utterly well? the lotus-lilies of the feet!

I tell you, it is no woman, it is no man, for I am alone.

And I fall asleep with the gods, the gods

that are not, or that are

according to the soul’s desire,

like a pool into which we plunge, or do not plunge.39

Feel free to be an atheist or an agnostic. You have free will: Your decision to disbelieve in the Gods is your choice, taken freely. But it is also your downfall. There are few things more hated by the dark God and all the Gods than a complete lack of belief. Atheism leads directly to the Machine. As for materialistic forms of religion and fundamentalism, these are forms of atheism.40 The dark God is not a jealous God: any one of the dark God’s manifestations may be freely worshiped. But, the dark God hates all those people who condemn their soul’s afterlife by their single-minded devotion to the allures of modern technology. These people have fallen out of grace, become robots, and nothingness is their end. Life can be both exceptionally beautiful and exceptionally difficult. The beauty is magnified many-fold for believers, and the Gods can give meaning to their suffering. No man or woman who suffers in this world, but loves the Gods, will go without reward in the hereafter. And as for a man who suffers in the name of the Gods, such as one who strives to build Rananim and establish places of peace and worship on earth, his place is exalted in the eyes of the great Gods. Men want so many things that amount to nothing in the end. Only their relationship with the Gods is of ultimate importance. Lawrence put it this way: “I want to be a man, with the gods beyond me, greater than me. I want the great gods, and my own mere manliness.”41 Life can be beautiful and simple: live joyfully, commune with nature, be in touch with the cosmos, and worship the Gods. No man should give his heart and soul to the great principle of evil, or the beguiling lure of modern technology, which promises an earthly paradise but ultimately causes so much sadness and devastation upon the face of the earth.

1.13. All sorts of gods.

There’s all sorts of gods, all sorts and every sort,

and every god that humanity has ever known is still a god today

the African queer ones and Scandinavian queer ones,

the Greek beautiful ones, the Phoenician ugly ones, the Aztec hideous

ones

goddesses of love, goddesses of dirt, excrement-eaters or lily virgins

Jesus, Buddha, Jehovah and Ra, Egypt and Babylon

all the gods, and you see them all if you look, alive and moving today,

and alive and moving tomorrow, many tomorrows, as yesterdays.

Where do you see them, you say?

You see them in glimpses, in the faces and forms of people, in glimpses.

When men and women, when lads and girls are not thinking,

when they are pure, which means when they are quite clean from self-

consciousness

either in anger or tenderness, or desire or sadness or wonder or mere

stillness

you may see glimpses of the gods in them.42

First there was the Fire, then there was the dark God. But the Fire exists wholly beyond time, and the dark God is both outside of and within time, so any sort of chronological statement about the Creation must be nothing more than a finger pointing at the moon. From the dark God sprang the Gods; innumerable Gods. As the dark God is infinite, there must be an indefinite multiplicity of Gods, meaning: more than one but we really don’t know how many. The Egyptian, Nordic, Hebrew, and Greek Gods all were real, and all are real.43 These Gods may not be believed in anymore, but a receptive man may still commune with any one, or all of these Gods. From the Gods came the cosmos, and all of life. Men and animals have immortal souls, but trees also have a connection to the Divine. Men have free will, and they have the choice to cultivate or waste their souls. Some men, when they die are reincarnated or enter some form of purgatory, some are in a hateful state, and some join the Gods. It may take many lifetimes for a man to come to the state where he achieves apotheosis. And yet, the soul, here and now, is already divine for those who will see it. Any man can come into touch with the Gods… And yet, they do not. There are men who are far greater than other men: Lawrence called these the sun-men: the saints, sages, prophets, and epic poets. These sun-men are pure, and are free from self-consciousness, hubris, egoism, and other spiritual defects. The Semitic conception of prophets is both true, in a limited fashion, and false in that it does not encompass the full reality of the prophets of the Gods. There have been innumerable prophets, in all places, and at all times. There is no difference between Buddha, Moses, and Muhammed, but there is also no difference between those prophets and the saints, such as Ibn Arabi, Francis of Assisi, or Plotinus. Not all prophets bring books or messages, and many prophets remain unknown. Not all prophets know the future, but they all have a living connection to at least one of the Gods. Now, the greater prophets are connected not only to one of the Gods, but to the dark God, and those men are god-men, sons of the dark God. Christ was one of these prophets, and for some who knew him personally, and many who have deeply studied most of his writings, so was D. H. Lawrence. Perhaps, D. H. Lawrence attained some form of union with the mystical body of Christ, and Lawrence’s arrival on earth prefigured the second coming of Christ, heralding the end times. We certainly are in the end times now, and Lawrence certainly laid out a path forward for believers in the end times, as a prophet would. He fought for good against the amassing forces of evil. As for the exact details of Lawrence’s role on earth, only the Gods know, so we simply state our intimations of the truth, as best we can. Now, the sun-men, as Lawrence understood them, have a connection to the Gods, but most men do not. But they can attain to a living connection with the Gods through the sun-men, who serve as the intermediaries of the Gods on earth. This is an extremely important principle in religion, and religions that deny this have gone seriously wrong. For all of its recent errors, the function of the Catholic priesthood is based on this vital truth.

Even for the saints who have a connection to the dark God, they may very well also have connections to the many Gods. Lawrence certainly had a vital connection to the dark God, but he was also deeply connected to all the Gods and Goddesses, along with the physical manifestations of the Gods. Lawrence could see the Gods in trees, lightning, and the faces of enlightened men. When one accepts the primordial vision, one accepts all of life’s beautiful realities. No single, manifested God can encompass all things. As Lawrence writes:

I prefer the pagan many gods, and the animistic vision. Here on this ranch at the foot of the Rockies, looking west over the desert, one just knows that all our Pale-face and Hebraic monotheistic insistence is a dead letter—the soul won’t answer any more. Here, when we have the camp just above the cabin, under the hanging stars, and we sit with the Indians round the fire, and they sing till late into the night, and sometimes we all dance the Indian tread-dance—then what is it to me, world unison and peace and all that. I am essentially a fighter—to wish me peace is bad luck—except the fighter’s peace. And I have known many things, that may never be unified: Ceylon, the Buddha temples, Australian bush, Mexico and Teotihuacan, Sicily, London, New York, Paris, Munich—don’t talk to me of unison. No more unison among man than among the wild animals—coyotes and chipmunks and porcupines and deer and rattlesnakes. They all live in these hills—in the unison of avoiding one another. As for “willing” the world into shape—better chaos a thousand times than any “perfect” world. […]

I know there has to be a return to the older vision of life. But not for the sake of unison. And not done from the will. It needs some welling up of religious sources that have been shut down in us: a great yielding, rather than an act of will: a yielding to the darker, older unknown, and a reconciliation. Nothing bossy. Yet the natural mystery of power.44

There is a single principle that is both beyond and behind everything, namely the Fire, but it is both one and many. There is one God, the dark God, but there are many Gods. This is not a contradiction. Ancient logic, particularly the logic of ancient Egypt, stated that something could be both yes and no, one and many, at the same time. The vision of radical non-dualism exemplified by certain strains of the Vedanta is extremely false, dangerous, and life-denying. In fact, pledging oneself to radical non-dualism is almost as dangerous as pledging oneself to the Machine. The manifestations of the true principle of existence are one and many, and are in constant flux. However, the principle itself exists outside of time and beyond being. Through its extension into existence, the dark God gave birth to the Gods and our souls, and the Gods created much of beauty. All this happened out of an abundance of love. To come back into closeness (but not union) to the Divine, we cannot exert force, but must become wholly receptive.

To reiterate, there is not only one manifestation of the Divine. God is one, but has been manifested as different gods, with different forms and names in different cultural and historical milieus. The number of Gods is unknown, and they encompass all of experience.45 There are not only Gods of peace and love, but also Gods of “fear, of darkness, of passion, and of silence,” as Lawrence writes:

There was not only one God. There was not only the God of love. To insist that there is only one God, and that God the source of Love, is perhaps as fatal as the complete denial of God, and of all mystery. He believed in the God of fear, of darkness, of passion, and of silence, the God that made a man realise his own sacred aloneness.46

When a man gets outside of his head, and starts to think creatively, through deeper faculties, such as the creative imagination, then the world of Gods and Goddesses opens in front of him. “In the fourth dimension, in the creative world, we live in a pluralistic universe, full of gods and strange gods, and unknown gods[.]”47 Since this creative faculty is, in essence, a religious faculty, many poets and artists, who were not necessarily saints, created works that can lead a person on the path towards the Divine. As Lawrence writes:

Everything that puts us into connection, into vivid touch, is religious. And this would apply to Dickens or Rabelais or Alice in Wonderland even, as much as to Macbeth or Keats. Every one of them puts us curiously into touch with life, achieves thereby certain religious feeling, and gives a certain religious experience. For in spite of all our doctrine and dogma, there are all kinds of gods, forever. There are gods of the hearth and the orchard, underworld gods, fantastic gods, even cloacal gods, as well as dying gods and phallic gods and moral gods. Once you have a real glimpse of religion, you realise that all that is truly felt, every feeling that is felt in true relation, every vivid feeling of connection, is religious, be it what it may, and the only irreligious thing is the death of feeling, the causing of nullity; the frictional irritation which, carried far, tends to nullity.

So that, since essentially the feeling in every real work of art is religious in its quality, because it links us up or connects us with life, you can’t substitute art for religion, the two being essentially the same. The man who has lost his religious response cannot respond to literature or to any form of art, fully: because the call of every work of art, spiritual or physical, is religious, and demands a religious response. The people who, having lost their religious connection, turn to literature and art, find there a great deal of pleasure, aesthetic, intellectual, many kinds of pleasure, even curiously sensual. But it is the pleasure of entertainment, not of experience. So that they gradually get tired out. They cannot give to literature the only thing it really requires—if it be important at all—and that is the religious response; and they cannot take from it the one thing it gives, the religious experience of linking up or making a new connection. For the religious experience one gets from Dickens belongs to Baal or Ashtaroth, but still it is religious: and in Wuthering Heights we feel the peculiar presence of Pluto and the spirit of Hades, but that too is of the gods. In Macbeth Saturn reigns rather than Jesus. But it is religious just the same.48

So, all true art is religious, but most modern Westerners, including those who claim to be religious, cannot see the spirituality suffused through the art. Conversely, all true religion is beautiful, but, sadly, many cannot see that either. Every true feeling is religious; not only love but anger. As Lawrence described above, the only truly irreligious feeling is a lack of feeling. Sadly, this lack of feeling is now the predominant feeling, and people who are already half-robots go to psychotherapists to get prescriptions for medicines that will complete the roboticization process.49 For these people, there is no hope. A man who is evil and commits murder may go to Hell for a time—though only for a time, since all shall eventually be saved—but a man who becomes a robot forfeits his soul,50 and nothingness is his end. As for the soul itself, it is immortal, but it is wiped clean of all personality. Conversely, the man who is even somewhat in touch with the Divine is granted the great miracle of immortality and personal continuance, though in ineffable forms. For the man whose communion with the Divine is incomplete, purgatory or reincarnation may await him.

1.14. God is Born

The history of the cosmos

is the history of the struggle of becoming.

When the dim flux of unformed life

struggled, convulsed back and forth upon itself, and broke at last into

light and dark

came into existence as light,

came into existence as cold shadow

then every atom of the cosmos trembled with delight:

Behold, God is born!

He is bright light!

He is pitch dark and cold!

And in the great struggle of intangible chaos

when, at a certain point, a drop of water began to drip downwards

and a breath of vapour began to wreathe up

Lo again the shudder of bliss through all the atoms!

Oh, God is born!

Behold, he is born wet!

Look, He hath movement upward! He spirals!

And so, in the great aeons of accomplishment and debacle

from time to time the wild crying of every electron:

Lo! God is born.

When sapphires cooled out of molten chaos:

See, God is born! He is blue, he is deep blue, he is forever blue!

When gold lay shining threading the cooled-off rock:

God is born! God is born! bright yellow and ductile He is born.

When the little eggy amoeba emerged out of foam and nowhere

then all the electrons held their breath:

Ach! Ach! Now indeed God is born! He twinkles within.

When from a world of mosses and of ferns

at last the narcissus lifted a tuft of five-point stars

and dangled them in the atmosphere,

then every molecule of creation jumped and clapped its hands:

God is born! God is born perfumed and dangling and with a little cup!

Throughout the aeons, as the lizard swirls his tail finer than water,

as the peacock turns to the sun, and could not be more splendid,

as the leopard smites the small calf with a spangled paw, perfect,

the universe trembles: God is born! God is here!

And when at last man stood on two legs and wondered,

then there was a hush of suspense at the core of every electron:

Behold, now very God is born!

God Himself is born!

And so we see, God is not

until he is born.

And also we see

there is no end to the birth of God51

Everything that exists ultimately emanates from the dark God. Even “lifeless” matter is from God. Nothing would exist without the Divine. The primordial Fire beyond being existed outside of existence, so it emanated the intermediary between itself and the realm of being, namely the dark God. The dark God is the highest principle in existence, but all that lives is connected to it. We are all the children of the God, and all that exists is due to the dark God constantly giving birth. The dark God, and all the polytheistic Gods, similar to all of creation, change constantly and never stay static. This is one of the miracles of existence, namely that something can in some sense be different and the same, at the same time. A man at seventy is both the same and different person as the child at ten. Even after death, an enlightened soul will continue to evolve. The Gods and the dark God all move, change, and flux, but they are now, and will always be. This is a great miracle. Life itself is a great miracle, and for this alone we should all be prostrating ourselves every moment of every day before the throne of the Divine. And yet, the one thing alone that is not divine is evil, which is the embodied principle of nothingness, emptiness, and death. We must get back into touch with the divine foundation of man and nature! We must be more like the ancients. We should all strive to see the Divine in all that is, and to fight against the mechanized and atheistic mindset of the modern world and all of its products. Lawrence instructs us as follows:

We can know the living world only symbolically. Yet every consciousness, the rage of the lion and the venom of the snake, is, and therefore is divine. All emerges out of the unbroken circle with its nucleus, the germ, the One, the God, if you like to call it so. And man, with his soul and his personality, emerges in eternal connection with all the rest. The blood-stream is one, and unbroken, yet storming with oppositions and contradictions.

The ancients saw, consciously, as children now see unconsciously: the everlasting wonder in things. […] But it was by seeing all things alert in the throb of inter-related passional significance that the ancients kept the wonder and the delight in life, as well as the dread and the repugnance. They were like children: but they had the force, the power and the sensual knowledge of true adults. They had a world of valuable knowledge, which is utterly lost to us. Where they were true adults, we are children; and vice versa.52

In order to get into touch, we need to extricate our minds from modern conceptions. We must strive to be more like the ancients. We can commune with the mountains while on the plains, a tree while lying in a field, a butterfly that flits by our faces, or the clouds while on the ground. Seeing the clouds from a plane will never get us metaphysically closer to the clouds; only the opening of the third eye will allow that to happen. In fact, all modern, mechanistic contrivances take us farther away than ever from any sort of communion with life or the Divine. As Klages writes:

Mechanistic materialization can never be metaphysical. Whoever takes a balloon-flight into the atmosphere does not merge himself with the elements, as does the soul of the wanderer who communes with the clouds whilst his conscious body yet abides upon the soil of the earth. Herein lies the launching-point for the comprehension of a myriad mysteries: the far.53

1.15. Middle of the World.

This sea will never die, neither will it ever grow old

nor cease to be blue, nor in the dawn

cease to lift up its hills

and let the slim black ship of Dionysos come sailing in

with grape-vines up the mast, and dolphins leaping.

What do I care if the smoking ships

of the P. & O. and the Orient Line and all the other stinkers

cross like clock-work the Minoan distance!

They only cross, the distance never changes.

And now that the moon who gives men glistening bodies

is in her exaltation, and can look down on the sun

I see descending from the ships at dawn

slim naked men from Cnossos, smiling the archaic smile

of those that will without fail come back again,

and kindling little fires upon the shores

and crouching, and speaking the music of lost languages.

And the Minoan Gods, and the Gods of Tiryns

are heard softly laughing and chatting, as ever;

and Dionysos, young, and a stranger

leans listening on the gate, in all respect.54

The oceans and seas are horribly polluted and are being treated like garbage dumps. This is a great calamity. But, as Lawrence teaches us, the essence of the great bodies of water will never change. The water may be corrupted, but the essence remains holy. Long after human civilization has passed away from this planet, the waters will be clean again, and great beasts will swim freely and with joy in the realms of the Gods of the waters.

If we want to be free from the taint of the Machine, we should become more like the maenads of Dionysus, namely wild, free, and in constant, ecstatic rapture due to a vital communion with the God. Alternatively, if we give ourselves over, even a little, to the products of machines, we start to become more machine-like. Lawrence describes how Italy went over to the side of the machines:

The machines were more to his soul than the sun. He did not know these mechanisms, their great, human-contrived, inhuman power, and he wanted to know them. As for the sun, that is common property, and no man is distinguished by it. He wanted machines, machine production, money, and human power. He wanted to know the joy of man who has got the earth in his grip, bound it up with railways, burrowed it with iron fingers, subdued it. He wanted this last triumph of the ego, this last reduction. He wanted to go where the English have gone, beyond the Self, into the great inhuman Not Self, to create the great unliving creators, the machines, out of the active forces of nature that existed before flesh.

But he is too old. It remains for the young Italian to embrace his mistress, the machine.

I sat on the roof of the lemon-house, with the lake below and the snowy mountain opposite, and looked at the ruins on the old, olive-fuming shores, at all the peace of the ancient world still covered in sunshine, and the past seemed to me so lovely that one must look towards it, backwards, only backwards, where there is peace and beauty and no more dissonance.

I thought of England, the great mass of London, and the black, fuming, laborious Midlands and north-country. It seemed horrible. And yet, it was better than the padrone, this old, monkey-like cunning of fatality. It is better to go forward into error than to stay fixed inextricably in the past.

Yet what should become of the world? There was London and the industrial counties spreading like a blackness over all the world, horrible, in the end destructive. And the Garda was so lovely under the sky of sunshine, it was intolerable. For away, beyond, beyond all the snowy Alps, with the iridescence of eternal ice above them, was this England, black and foul and dry, with her soul worn down, almost worn away. And England was conquering the world with her machines and her horrible destruction of natural life. She was conquering the whole world.

And yet, was she not herself finished in this work? She had had enough. She had conquered the natural life to the end: she was replete with the conquest of the outer world, satisfied with the destruction of the Self. She would cease, she would turn round; or else expire.

If she still lived, she would begin to build her knowledge into a great structure of truth. There it lay, vast masses of rough-hewn knowledge, vast masses of machines and appliances, vast masses of ideas and methods, and nothing done with it, only teeming swarms of disintegrated human beings seething and perishing rapidly away amongst it, till it seems as if a world will be left covered with huge ruins, and scored by strange devices of industry, and quite dead, the people disappeared, swallowed up in the last efforts towards a perfect, selfless society.55

The Machine is the great “Not Self,” it is Nothingness, it is “Death, the destroyer of worlds.” The people of the industrialized countries, and now the people of nearly all countries, have poisoned the earth, air, and water. Either they will learn from their mistakes now or everything collapses. Either way, the Machine will collapse, and the Gods will triumph. Either way involves suffering. But, to embrace the former path, the path of the Gods, the path to Rananim, is to save one’s soul, whereas to let the Machine destroy everything on earth is to lose one’s soul and earn the displeasure of the Gods. Ultimately, however, life will prevail. Even the great power of the Machine cannot harm the Gods. Dionysus, Jesus, and Osiris have taught us that life always prevails and that there is no death. All that lives is holy and shall be resurrected. Only the Machine will experience death, since it is Death, and contains nothing of life within itself. Once we give ourselves over to Dionysus, we are reborn and become free from the cycles of birth and death. As Klages writes:

Dionysus is the releasing god: Eleusis, Lysios. In him the spheres expropriate themselves through commingling. Death in him is eternal rebirth and the meaning of life. Here every tension releases itself and all opposites coalesce. Dionysus is the symbol of the whirlpool; he is chaos as it glowingly gives birth to the world.

In the ego-god, however, we find only an oppressive “truth,” an emphasis on purpose (Socrates), and a “beauty of soul” that negates the beauty of the body (mortification of the flesh). Just as one rightly calls Dionysus the releaser, so should Jesus Christ be called the represser, because repression is the limiting power that enabled him to conquer so many nations, just as he will, perhaps, eventually conquer all. What Alfred Schuler called his “eagerness for love,” can only repress; it can never release. The paradox here is that Jesus insists that he alone is the “redeemer,” i.e., the one who releases!56

Now, Klages is completely correct regarding Dionysus, but he was too much of a Nietzschean to have escaped his prejudicial views of Christ. Klages’ views about Christ are aptly applied to large swathes of Christianity, but not all Christianity, and certainly not Christ, who was and is a great releasing God.

1.16. The Body of God

God is the great urge that has not yet found a body

but urges towards incarnation with the great creative urge.

And becomes at last a clove carnation: lo! that is god!

and becomes at last Helen, or Ninon; any lovely and generous woman

at her best and her most beautiful, being god, made manifest,

Any clear and fearless man being god, very god.

There is no god

apart from poppies and the flying fish,

men singing songs, and women brushing their hair in the sun.

The lovely things are god that has come to pass, like Jesus came.

The rest, the undiscoverable, is the demi-urge.57

The primordial Fire is bodiless and beyond being. The dark God was all alone and bodiless so it emanated itself from itself, leading to the Gods and the cosmos. We are all emanations of the dark God; we are all the body of God. As all that is alive is part of the body of God, defiling that body through pollution is akin to a man’s hand trying to mutilate his foot. All forms of defiling of nature are a grave sin. As we discussed earlier, we are not supportive of much of the exoteric emphasis on sin, but there are certain deadly sins, and they include pollution and any form of alliance with the Machine. To escape from our deadly sins and the clutches of the Machine, we must worship the Gods and we must bow down before the dark God. And how to do this? Since all is holy, tree worship is a way, but another, greater way is through the worship of the divine essences behind the sun and moon. If we can come into vital touch with the sun and moon, the rest will surely follow. As Lawrence writes:

Poor, paltry, creeping little world we live in, even the keys of death and Hades are lost. How shut in we are! All we can do, with our brotherly love, is to shut one another in. We are so afraid somebody else might be lordly and splendid, when we can’t. Petty little bolshevists, every one of us today, we are determined that no man shall shine like the sun in full strength, for he would certainly outshine us.

Now again we realise a dual feeling in ourselves with regard to the Apocalypse. Suddenly we see some of the old pagan splendour, that delighted in the might and the magnificence of the cosmos, and man who was as a star in the cosmos. Suddenly we feel again the nostalgia for the old pagan world, long before John’s day, we feel an immense yearning to be freed from this petty personal entanglement of weak life, to be back in the far-off world before men became “afraid”. We want to be freed from our tight little automatic “universe”, to go back to the great living cosmos of the “unenlightened” pagans!

Perhaps the greatest difference between us and the pagans lies in our different relation to the cosmos. With us, all is personal. Landscape and the sky, these are to us the delicious background of our personal life, and no more. Even the universe of the scientist is little more than an extension of our personality, to us. To the pagan, landscape and personal background were on the whole indifferent. But the cosmos was a very real thing. A man lived with the cosmos, and knew it greater than himself.