Democracy

The Machine Will Never Triumph, part twenty-four

Democracy

I am a democrat in so far as I love the free sun in men

and an aristocrat in so far as I detest narrow-gutted, possessive

persons.

I love the sun in any man

when I see it between his brows

clear, and fearless, even if tiny.

But when I see these great successful men

so hideous and corpse-like, utterly sunless

like gross successful slaves grossly waddling

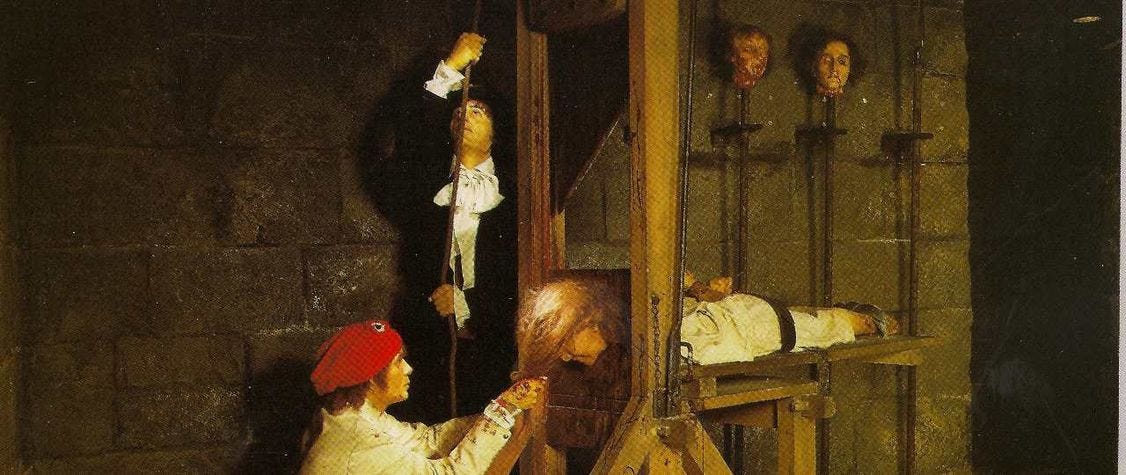

then I am more than radical, I want to work a guillotine.

And when I see working men

pale and mean and insect-like, scuttling along

and living like lice, on poor money

and never looking up,

Then I wish, like Tiberius, the multitude had only one head

so that I could lop it off.

I feel that when people have gone utterly sunless

they shouldn’t exist.1

Here we have a brief statement from Lawrence regarding his views of the sun-men, democracy, and the upper and lower classes. Lawrence believes that democracy is an ineffectual system, since it relies on popular opinion, rather than spiritual acumen, as a judge of who should rule. As we can see with recent elections in the United States, democracy too often leads to poor outcomes and the election of bumbling fools. Unlike Marxists, who take the side of the lower classes, Lawrence abhors the lower-class masses for their robot-like automatism. Unlike certain traditionalists and conservatives, Lawrence also despises the upper classes for all the harm they do to the world and humanity. What Lawrence wants is a new way—not a system—where those who rule, rule because they have a deep spiritual connection to the cosmos and to the Gods. These rulers would not rule for power or money, but out of a devotion to the religion of life and a devotion to their constituents’ ability to attain their highest spiritual aspirations. As for the lower classes and upper classes who are sunless and robotic, Lawrence—rightfully—wishes them to go the way of the dodo bird.

Lawrence vastly prefers aristocracy to democracy, and rightly so. The privileged classes of today, who rule, are not the best; they are simply the wealthiest. Their empire is an empire of dirt. Lawrence’s magisterial take-down of democracy and plutocracy is as follows:

I hate democracy[…] “Only the greedy and ugly people come to the top in a democracy,” she said, “because they’re the only people who will push themselves there. Only degenerate races are democratic.” […] “I do want an aristocracy,” she cried. “And I’d far rather have an aristocracy of birth than of money. Who are the aristocrats now—who are chosen as the best to rule? Those who have money and the brains for money. It doesn’t matter what else they have: but they must have money-brains,—because they are ruling in the name of money.” […] [W]hat are the people? Each one of them is a money-interest. I hate it, that anybody is my equal who has the same amount of money as I have. I know I am better than all of them. I hate them. They are not my equals. I hate equality on a money basis. It is the equality of dirt.”2

Interestingly, the traditional propaganda coming out of Western states claims that communism destroys individuality—which is true—but western-style democracy and capitalism also destroy individuality. When the only choice you have of what to wear is a choice between hundreds of mass-produced, machine-made garments, that is no choice at all. Whether one runs into a stranger in the street wearing the same shirt and pair of jeans, or everyone wears the universal khaki, the result is the same, but capitalism is worse. Under true socialism, however, one is not constrained by fear of money or lack thereof, and so one can happily become an artist and express his or her creativity without fear of starvation. Lawrence aptly describes democracy’s pitiful leveling effect:

Usually, however, the peasants of the South have left off the costume. Usually it is the invisible soldiers’ grey-green cloth, the Italian khaki. Wherever you go, wherever you be, you see this khaki, this grey-green war-clothing. How many millions of yards of the thick, excellent, but hateful material the Italian government must have provided I don’t know: but enough to cover Italy with a felt carpet, I should think. It is everywhere. It cases the tiny children in stiff and neutral frocks and coats, it covers their extinguished fathers, and sometimes it even encloses the women in its warmth. It is symbolic of the universal grey mist that has come over men, the extinguishing of all bright individuality, the blotting out of all wild singleness. Oh democracy! Oh khaki democracy!3

True individuality is not shown in a highly socialized modern city-dweller. Most city dwellers are not individuals; they are deluded. It is the simple peasant who expresses the highest degree of true individuality, with his simple life and his handmade costume. Lawrence writes:

Sometimes, in the distance one sees a black-and-white peasant riding lonely across a more open place, a tiny vivid figure. I like so much the proud instinct which makes a living creature distinguish itself from its background. I hate the rabbity khaki protection-colouration. A black-and-white peasant on his pony, only a dot in the distance beyond the foliage, still flashes and dominates the landscape. Ha-ha! proud mankind! There you ride! But alas, most of the men are still khaki-muffled, rabbit-indistinguishable, ignominious. The Italians look curiously rabbity in the grey-green uniform: just as our sand-colored khaki men look doggy. They seem to scuffle rather abased, ignominious on the earth. Give us back the scarlet and gold, and devil take the hindmost.4

Though the roots of modernity and democracy lie in Europe, the real basis for modern democracy, capitalism, and the Machine was colonial America. The genocide of the Native Americans, the slave trade, and the erection of massive factories sealed America’s fate. Now, over three hundred years later, the pattern of this social structure has spread to nearly the entire globe, and subjected the bulk of mankind to its maddening and degrading effects. Lawrence writes:

The New Englanders, wielding the sword of the spirit backwards, struck down the primal impulsive being in every man, leaving only a mechanical, automatic unit. In so doing they cut and destroyed the living bond between men, the rich passional contact. And for this passional contact gradually was substituted the mechanical bond of purposive utility. The spontaneous passion of social union once destroyed, then it was possible to establish the perfect mechanical concord, the concord of a number of parts to a vast whole, a stupendous productive mechanism. And this, this vast mechanical concord of innumerable machine-parts, each performing its own motion in the intricate complexity of material production, this is the clue to western democracy.

It has taken more than three hundred years to build this vast living machine.5

The middle-classes

The middle classes

are sunless.

They have only two measures:

mankind and money,

they have utterly no reference to the sun.

As soon as you let people be your measure

you are middle-class and essentially non-existent.

Because, if the middle classes had no poorer people to be superior to

they would themselves at once collapse into lower-classness.

And if they had no upper classes either, to be inferior to,

they wouldn’t suddenly become themselves aristocratic,

they’d become nothing.

For their middleness is only an unreality separating two realities.

No sun, no earth,

nothing that transcends the bourgeois middlingness,

the middle classes are more meaningless

than paper money when the bank is broke.6

Democracy is the political system of the middle classes, but as Lawrence makes clear, the middle classes are meaningless. The wealthy rule the world, and the lower classes are the grease that keeps the Machine running, but the middle classes are a null void, and their lives are meaningless and empty. It is much more common to find the sun shining from the brow of one of the upper classes, or even one of the impoverished lower classes, than to see it in a man of the vast middling classes. Money is meaningless, earthly power is largely meaningless. Only the direct life-affirming power of the sun has meaning, and that power only comes to those who know the Gods. Of course, finding a sun-man, one who knows the Gods, in the midst of this machine-world is increasingly difficult. There was an old saying that the only difference between the Americans and Soviets is that the Americans believed the propaganda they were fed. Well, they still do believe the propaganda. As Spengler makes clear, democracy is itself a form of slavery:

Man does not speak to man; the press and its associate, the electrical news-service, keep the waking-consciousness of whole peoples and continents under a deafening drum-fire of theses, catchwords, standpoints, scenes, feelings, day by day and year by year, so that every Ego becomes a mere function of a monstrous intellectual Something. Money does not pass, politically, from one hand to the other. It does not turn itself into cards and wine. It is turned into force, and its quantity determines the intensity of its working influence. […] Today we live so cowed under the bombardment of this intellectual artillery that hardly anyone can attain to the inward detachment that is required for a clear view of the monstrous drama. The will-to-power operating under a pure democratic disguise has accomplished its task so well that the object’s sense of freedom is actually flattered by the most thorough-going enslavement that has ever existed.7

The Buddha knew that all systems were slave systems, and all attachments were jail-houses for the soul. The genius of capitalist consumerism is that it creates multitudinous jails, keeps the doors open, then convinces people that they actually want the prison-life. To possess a car, to own a large house, to own objects, or to be in any way part of the system is to imprison oneself. The only freedom is not a freedom to buy what you want, but to be free of the desire to have anything at all. Even the CEOs of major companies are not free (perhaps they are the most enslaved of all). Only those who have learned detachment, such as monks, nuns, and the sun-men, like Lawrence, can be said to be free. The ideologies of democracy, and consumerism have sadly infiltrated most of the countries of the world. Lawrence makes clear this disastrous turn of events:

Sayula also had that real insanity of America, the automobile. As men used to want a horse and a sword, now they want a car. As women used to pine for a home and a box at the theatre, now it is a “machine.” And the poor follow the middle class. There was a perpetual rush of “machines,” motor-cars and motor-buses—called camiones—along the one forlorn road coming to Sayula from Guadalajara. One hope, one faith, one destiny; to ride in a camión, to own a car.8

Not everyone who is born has the same vocation. Many people would be far happier, and far better off, if they remained illiterate and worked in fields. Even those with an intellectual vocation should be careful to stay away from much of what is written. Much of what comes out of the academy and exists in print is intellectual garbage, and the books should never have been published. Since the books do exist, serious seekers should exercise great caution and careful judgment on what to avoid. Instead, read the great classics and the writings of the great saints and sages, such as Simone Weil, or simply get your nourishment from someone you acknowledge as prophetic, such as I do with Lawrence, may the Gods bless us through his work. As Lawrence writes:

I count it a mistake of our mistaken democracy, that every man who can read print is allowed to believe that he can read all that is printed. I count it a misfortune that serious books are exposed in the public market, like slaves exposed naked for sale. But there we are, since we live in an age of mistaken democracy, we must go through with it.9

Modern democracy is based on the majority, on the average, and, to a great deal, on data abstractions. The abstract average man does not exist. If a man is “average,” he has ceased to be anything more than a robot. A real man is a unique being, a phenomenon unto itself. As Lawrence writes:

What is the Average Man? As we are well aware, there is no such animal. It is a pure abstraction. It is the reduction of the human being to a mathematical unit. Every human being numbers one, one single unit. That is the grand proposition of the Average.10

For those of us who abhor modernity, technology, democracy, and all systems, life can sometimes feel overwhelmingly difficult in the face of the relentless onslaught of the Machine. For these moments of self-doubt and despondence, Jeffers has some wise words:

The extraordinary patience of things!

This beautiful place defaced with a crop of suburban houses—

How beautiful when we first beheld it,

Unbroken field of poppy and lupin walled with clean cliffs;

No intrusion but two or three horses pasturing,

Or a few milch cows rubbing their flanks on the outcrop rock-heads—

Now the spoiler has come: does it care?

Not faintly. It has all the time. It knows people are a tide

That swells and in time will ebb, and all

Their works dissolve. Meanwhile the image of pristine beauty

Lives in the very grain of the granite,

Safe as the endless ocean that climbs our cliff.—As for us:

We must unhumanize our views a little, and become confident

As the rock and ocean that we are made from.11

Liberty’s old story

Men fight for liberty, and win it with hard knocks.

Their children, brought up easy, let it slip away again, poor fools.

And their grandchildren are once more slaves.12

The sad story of liberty is that the only ones who understand it are those who fight for it. The following generations always let liberty slip through their fingers. What can today’s freedom fighters do to make sure this never happens? Realistically, not much, since all things in life are, by nature, transitory. The best solution, if we were able to free ourselves from the Machine, is to have our best poets and story-tellers create mythologies that warn us against the dangers of technology. That and setting in place a social hierarchy, which would limit the scope of scientific inquiry. That may be the best solution, though even if we save the world today, it may be that the world will be destroyed tomorrow by our offspring if they fail to observe those limits.

As far as freedom itself goes, some of the freest people are the most constrained. A monk need not worry about ninety-nine percent of what the average man of today concerns himself with: this is true freedom. To be free only to buy and sell, but to be forced to keep a job you despise in order to eat is comparable, in many ways, to slavery. As Lawrence, at his most pessimistic, wrote:

There is no such thing as liberty. The greatest liberators are usually slaves of an idea. The freest people are slaves to convention and public opinion, and more still, slaves to the industrial machine. There is no such thing as liberty. You only change one sort of domination for another. All we can do is to choose our master.13

Regarding the historical connections between the rise of democracy in America and the concomitant rise of the Machine, Lawrence states the following:

Uprooted from the native soil […] [t]he natural impulsive being withered, the deliberate, self-determined being appeared in his place. There was soon no more need to militate directly against the impulsive body. This once dispatched, man could attend to the deliberate perfection in mechanised existence[…] [T]he American[, …] having conquered and destroyed the instinctive, impulsive being in himself, he is free to be always deliberate, always calculated, rapid, swift, and single in practical execution as a machine. The perfection of machine triumph, of deliberate self-determined motion, is to be found in the Americans[…] They must run on, like machines, or go mad. The only difference between a human machine and an iron machine is that the latter can come to an utter state of rest, the former cannot. No living thing can lapse into static inertia, as a machine at rest lapses. And this is where life is indomitable. It will be mechanised, but it will never allow mechanical inertia[…] And yet it cannot be for this alone that the millions have crossed the ocean. This thing, this mechanical democracy, new and monstrous on the face of the earth, cannot be an end in itself. It is only a vast intervention, a marking-time, a mechanical life-pause. It is the tremendous statement in negation of our […] being.14

To be uprooted, to have wiped out an indigenous people: these things brought on the curse of the Machine. But, as Lawrence mentions, life can never lie perfectly fallow like machines can. Life will always triumph over machine-like death. Just as a field may need rest for a time, perhaps the great mechanical death-wave we find drowning the planet may yet result in a great resurgence of life.

Those minions of the Machine who want to keep the current system will by and large not resort to violence as it has proven to be counter-productive. Modern technology has far more subtle, and hence far more nefarious, means of control. Louis-Ferdinand Céline describes this phenomenon:

Wielding a club is fatiguing in the long run. The white men’s hearts and minds, on the other hand, have been crammed full of the hope of becoming rich and powerful, and that costs nothing, absolutely nothing. We’ve heard enough about Egypt and the Tatar tyrants! In the art of squeezing the last ounce of labor out of a two-legged animal, those primitive ancients were pretentious incompetents! Did they ever think of calling their slave “Monsieur” or letting him vote now and then, or giving him his newspaper? And especially had they thought of sending him to war to work off his passions? After twenty centuries of Christianity (as I personally can bear witness) your modern man simply can’t control himself when a regiment passes before his eyes. It puts too many ideas into his head.15

Ironically, those who know technology best may be in a better place to critique it than some of those who claim to be neutral or to reject it. In order to reject or affirm something, one must either understand it well or have a deep, passionate, intuitive understanding that allows one to make an informed decision. Interestingly, one of the better responses to Ted Kaczynski’s manifesto came from Bill Joy, founder of Sun Microsystems. You can’t stay neutral on a moving train. We must understand the diabolical nature of technology in order to overthrow it, and to allow the free flow of life back into the world. Heidegger makes these points clear as follows:

Everywhere we remain unfree and chained to technology, whether we passionately affirm or deny it. But we are delivered over to it in the worst possible way when we regard it as something neutral; for this conception of it, to which today we particularly like to do homage, makes us utterly blind to the essence of technology.16

Democracy is Service

Democracy is service, but not the service of demos.

Democracy is demos serving life

and demos serves life as it gleams on the face of the few,

and the few look into the eyes of the gods, and serve the sheer gods.17

Today we serve the state, and the state only serves us in the way that a waiter at a four-star restaurant would serve up a filet mignon to a hungry guest. The state that we serve, serves us up to the Machine. No one should ever serve a state, nor should he ever serve an abstract ideal. Instead the demos should serve life. Life comes direct from the Gods, and so to serve life is to serve the Gods, and to serve the Gods is to serve those people who have the gleam of the Gods in their eyes. As for the robotic masses, they can serve the god-men, the sun-men. As Lawrence writes:

You’ve got to have a sort of slavery again. People are not men: they are insects and instruments, and their destiny is slavery. They are too many for me, and so what I think is ineffectual. But ultimately they will be brought to agree—after sufficient extermination—and then they will elect for themselves a proper and healthy and energetic slavery.18

For, a “proper and healthy and energetic slavery” is so much better than what we have.

False democracy and real.

If man only looks to man, and no-one sees beyond

then all is lost, the robot supervenes.

The few must look into the eyes of the gods, and obey the look

in the eyes of the gods:

and the many must obey the few that look into the eyes of the gods;

and the stream is towards the gods, not backwards, towards man.19

This is a clear statement of Lawrence’s criticism of democracy and support for a form of spiritual aristocracy. To make man the measure is to lower man beneath the animals. All animals have eyes that burn with the fire of the Gods. When our eyes go dull, we become robots, and then we are lower than worms. The few great men of the world must find the Gods, and look deep into their essences; then they must communicate the life-power they received by the Grace of the Gods to the whole world. As for the masses of men who have not seen the Gods, they must serve those sun-men who know the Divine. We must reverse the tide back to the Gods and away from man and machine. What’s needed is a restoration of the primordial sense of the sacred that modern humanism and reliance on technological ingenuity has supplanted. Now, please don’t misunderstand Lawrence here. He would abhor all kinds of modern dictatorship and authoritarianism as much as he hated democracy. Remember, he was vociferously against the machinations of Mussolini. What Lawrence wants is something new, a true spiritual aristocracy, but one where even the lowliest person can become great through a connection with the Gods. As for the world, as it is, we must learn to be detached in a certain sense from the terrible events of the day. Lawrence knew that we must live apart from the machine-world, and though he puts it in different language, his message is not dissimilar to that of Kamo no Chōmei’s Hojoki. Lawrence writes:

Now art is degraded beneath mention, really trampled under the choice of a free democracy, a public opinion. When I think of art, and then of the British public—or the French public, or the Russian—then a sort of madness comes over me, really as if one were fastened with a mob, and in danger of being trampled to death. I hate the “public”, the “people”, “society”, so much, that a madness possesses me when I think of them. I hate democracy so much. It almost kills me. But then, I think that “aristocracy” is just as pernicious, only it is much more dead. They are both evil. But there is nothing else, because everybody is either “the people” or “the Capitalist”.

One must forget, only forget, turn one’s eyes from the world: that is all. One must live quite apart, forgetting, having another world, a world as yet uncreated. Everything lies in being, although the whole world is one colossal madness, falsity, a stupendous assertion of not-being.20

Bibliography

Céline, Louis-Ferdinand. Journey to the End of the Night. Translated by Ralph Manheim. New York: New Directions, 2006.

Heidegger, Martin. The Question Concerning Technology. Translated by William Lovitt. New York: Harper Perennial, 2013.

Jeffers, Robinson. The Collected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers. Edited by Tim Hunt. Vol. Three. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1988.

Lawrence, D. H. Aaron’s Rod. Edited by Mara Kalnins. New York: Penguin Books, 1995.

———. Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious. Edited by Bruce Steele. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

———. Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays. Edited by Michael Herbert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

———. “Sea and Sardinia.” In D. H. Lawrence and Italy, 137–326. London: Penguin Books, 2007.

———. Studies in Classic American Literature. Edited by Ezra Greenspan, Lindeth Vasey, and John Worthen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

———. The Plumed Serpent. Edited by L. D. Clark. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

———. The Poems. Edited by Christopher Pollnitz. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

———. The Rainbow. London: Everyman’s Library, 1993.

———. The Selected Letters of D. H. Lawrence. Edited by James T. Boulton. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Spengler, Oswald. The Decline of the West. Edited by Arthur Helps and Helmut Werner. Translated by Charles Francis Atkinson. New York: Vintage Books, 2006.

D. H. Lawrence, The Poems, ed. Christopher Pollnitz, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 457.

D. H. Lawrence, The Rainbow (London: Everyman’s Library, 1993), 427–28.

D. H. Lawrence, “Sea and Sardinia,” in D. H. Lawrence and Italy (London: Penguin Books, 2007), 205.

ibid., 219–20.

D. H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature, ed. Ezra Greenspan, Lindeth Vasey, and John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 176.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:458.

Oswald Spengler, The Decline of the West, ed. Arthur Helps and Helmut Werner, trans. Charles Francis Atkinson (New York: Vintage Books, 2006), 394.

D. H. Lawrence, The Plumed Serpent, ed. L. D. Clark (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 112.

D. H. Lawrence, Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 62.

D. H. Lawrence, Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays, ed. Michael Herbert (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 63.

Robinson Jeffers, The Collected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers, ed. Tim Hunt, vol. Three (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1988), 399.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:465.

Lawrence, The Plumed Serpent, 72.

Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature, 176–77.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Journey to the End of the Night, trans. Ralph Manheim (New York: New Directions, 2006), 119.

Martin Heidegger, The Question Concerning Technology, trans. William Lovitt (New York: Harper Perennial, 2013), 4.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:560.

D. H. Lawrence, Aaron’s Rod, ed. Mara Kalnins (New York: Penguin Books, 1995), 281.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:560.

D. H. Lawrence, The Selected Letters of D. H. Lawrence, ed. James T. Boulton (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 126–27.

Just a note to thank you for your chapters so far, Farasha. I have very much enjoyed reading them. I'm reading Hamsun's Growth of the Soil at the moment and find myself wondering if Lawrence read him, as I see affinities. He was surely aware of Hamsun, given the Nobel Prize and all that.