Cosmology

The Machine Will Never Triumph, part forty-eight

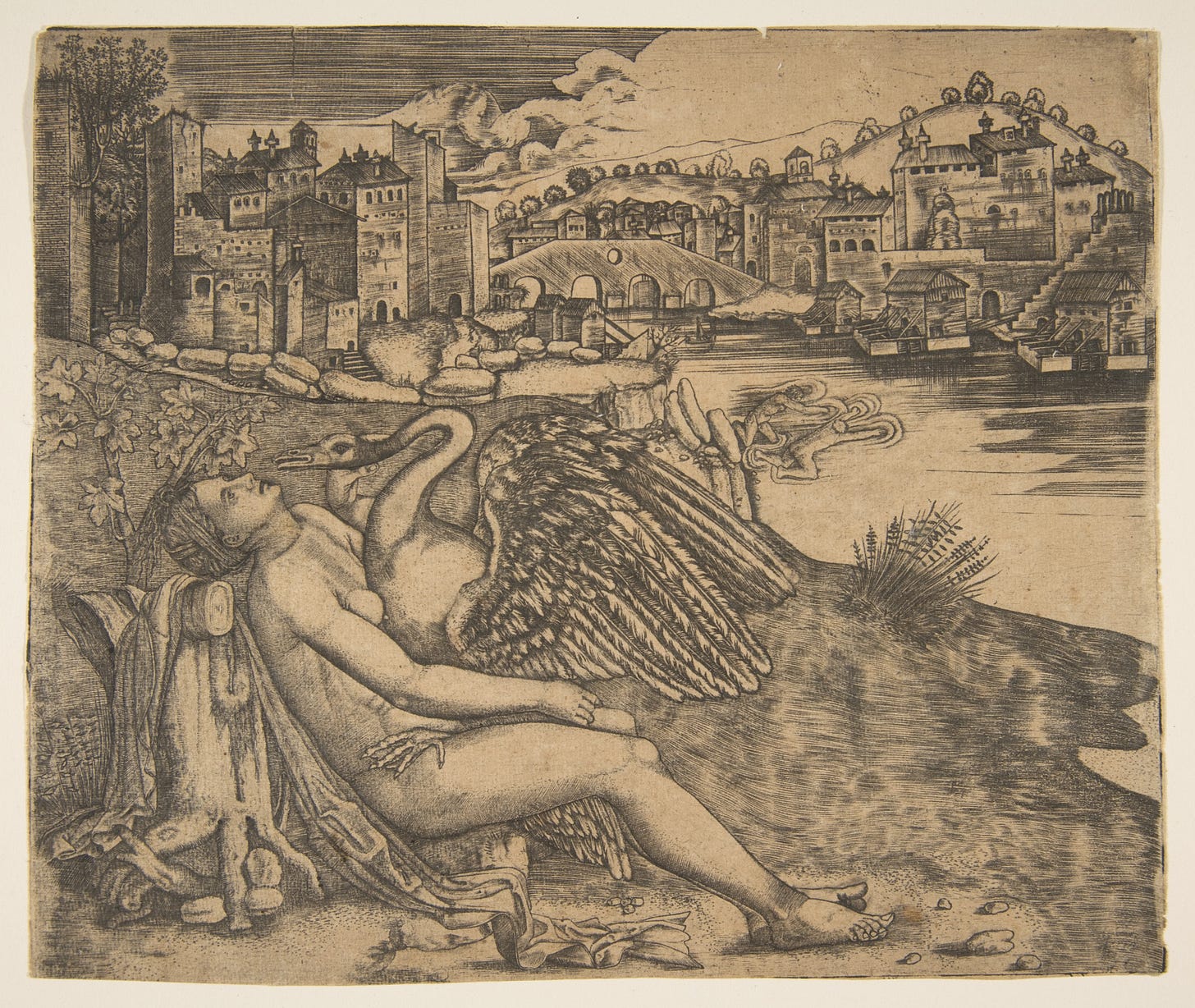

Swan

Far-off

at the core of space

at the quick of time

beats

and goes still

the great swan upon the water of all endings

the swan within vast chaos, within the electron.

For us

no longer he swims calmly

nor clacks across the forces furrowing a great gay trail

of happy energy,

nor is he nesting passive upon the atoms,

nor flying north desolative icewards

to the sleep of ice,

nor feeding in the marshes,

nor honking horn-like into the twilight.—

But he stoops, now

in the dark

upon us;

he is treading our women

and we men are put out

as the vast white bird

furrows our featherless women

with unknown shocks

and stamps his black marsh-feet on their white and marshy flesh.1

The swan that beats within the electron is the principle of life that emanates from the primordial Fire, and which enlivens all things. Most modern people don’t believe in such a vital cosmic principle, but believe it or not, it is there, and it flows through all things. The swan that beats through our hearts enlivens us if we believe in it and the Gods, but if we rebel against nature and destroy the world through hubristic sadism, then the swan has its revenge upon our souls.

There are two great metaphysical options: the positive, invoking the many Gods, and the negative, denying them all. The former is the path of antiquity, and the latter is the modern path. Monotheistic religion is, largely, a stepping stone on the path to atheism. A man has many needs in life, the Gods above all. A man should worship and know all the Gods, and though he may primarily invoke a certain deity, it behoves him to honor and respect them all. All Gods, including the monotheistic Gods, should be invoked with love. The Fire beats strongly in all of them. As Lawrence writes:

The pagan way, the many gods, the different service, the sacred moments of Bacchus. Other sacred moments: Zeus and Hera, for examples, Ares and Aphrodite, all the great moments of the gods. Why not know them all, all the great moments of the gods, from the major moment with Hera to the swift short moments of Io or Leda or Ganymede? Should not a man know the whole range? And especially the bright, swift, weapon-like Bacchic occasion, should not any man seize it when it offered?2

There is a Fire that is prior to time and beyond being. That Fire is at the root of all that is. Everything that exists in the realm of manifestation is suffused with the energy of the Fire, namely the Swan. The greatest entities within the realms of manifestation are the immortal Gods. There are great Gods and small Gods, light Gods, and dark Gods. We exist within the realm of manifestation, but we are suffused with Fire to the extent that we give ourselves over to the Gods and develop an organic connection to all that lives. The root of all connections is a home, and our home is earth. Without a home, there can be no roots, and without roots it is impossible to develop connections to the principle of Life. Life flows, and the Fire is in flux, but we can avoid being swept away if we are anchored, and our anchor is our home. As soon as we started destroying earth and believing the universe to be a meaningless infinity, we became uprooted and unanchored, which has caused untold disasters for the human race and all of creation on this planet. The idea that we live in an infinite universe is a trap. Only within limits can we be truly free. Just as most men need to give allegiance to a sun-man to be free, most people need to be confined to a place to be free. Who is freer, the international globetrotter, or the small farmer? It is the latter. The former will never feel content, no matter how far he travels, but the latter already has a whole world at his fingertips. As Lawrence writes:

I have read books of astronomy which made me dizzy with the sense of illimitable space. But the heart melts and dies, it is the disembodied mind alone which follows on through this horrible hollow void of space, where lonely stars hang in awful isolation. And this is not a release. It is a strange thing, but when science extends space ad infinitum, and we get the terrible sense of limitlessness, we have at the same time a secret sense of imprisonment. Three-dimensional space is homogenous, and no matter how big it is, it is a kind of prison. No matter how vast the range of space, there is no release.3

We have a deep-seated need for roots. All that modern science, astronomy, and cosmology lead to are rootlessness, depression, and anxiety. Whatever material advantages the modern world may offer, there is no doubt that ancient peoples were far happier. When people were connected to the land and to local communities, and knew that the Gods are real, depression, anxiety, and suicide were almost unheard of. Ultimately, all the other debates aside, modernity has failed to bring happiness, and has only brought depression and sowed the seeds of death. As such, we should strive to end the disease of modernity and should work towards a reinvigorated tradition and rootedness to people, place, and the cosmos.

Give us gods

Give us gods, Oh give them us!

Give us gods.

We are so tired of men

and motor-power.—

But not gods grey-bearded and dictatorial,

nor yet that pale young man afraid of fatherhood

shelving substance on to the woman, Madonna mia! shabby virgin!

nor gusty Jove, with his eye on immortal tarts,

nor even the musical, suave young fellow

wooing boys and beauty.

Give us gods

give us something else—

Beyond the great bull that bellowed through space, and got his throat cut.

Beyond even that eagle, that phoenix, hanging over the gold egg of all

things,

further still, before the curled horns of the ram stepped forth

or the stout swart beetle rolled the globe of dung in which man should

hatch,

or even the sly gold serpent fatherly lifted his head off the earth to think—

Give us gods before these—

Thou shalt have other gods before these.

Where the waters end in marshes

swims the wild swan

sweeps the high goose above the mists

honking in the gloom the honk of procreation from such throats.

Mists

where the electron behaves and misbehaves as it will,

where the forces tie themselves up into knots of atoms

and come untied;

mists

of mistiness complicated into knots and clots that barge about

and bump on one another and explode into more mist, or don’t,

mist of energy most scientific—

But give us gods!

Look then

where the father of all things swims in a mist of atoms

electrons and energies, quantums and relativities

mists, wreathing mists,

like a wild swan, or a goose, whose honk goes through my bladder.

And in the dark unscientific I feel the drum-winds of his wings

and the drip of his cold, webbed feet, mud-black

brush over my face as he goes

to seek the women in the dark, our women, our weird women whom he

treads

with dreams and thrusts that make them cry in their sleep.

Gods, do you ask for gods?

Where there is woman there is swan.

Do you think, scientific man, you’ll be father of your own babies?

Don’t imagine it.

There’ll be babies born that are cygnets, O my soul!

young wild swans!

And babies of women will come out young wild geese, O my heart!

the geese that saved Rome, and will lose London.4

We need Gods even more than we need water or bread. The Machine is the great anti-divine principle operating in the world, and all of modernity’s technological contrivances are appendages of the Machine. We need Gods. Yes, we need Allah, Zeus, Odin, and Osiris, but we desperately need the Gods beyond these Gods. Before and beyond all the anthropomorphic and human-centered Gods, there were the primordial Gods without human-conditioned shape or form. All of the elements, all of nature, everything that lives, and everything that is, is full of Gods. Rather than proving scientific hypotheses, the world of the atom should show all those with eyes to see, the spiritual reality at the core of all that exists. Where there are men and women, real men and women, not eunuch robots, there is the reverberating fecund power of the dark Gods, the Gods without shape or form, but with life straight from the primordial Fire. We have only two choices: the Gods or the Machine. As Edward Abbey writes, the entire modern edifice, including science, is beholden to the Machine:

Pure science is a myth; both mathematical theoreticians like Albert Einstein and practical crackpots like Henry Ford dealt with different aspects of the same world; theory and practice, invention and speculation, calculus and metallurgy have always functioned closely together, feeding upon and reinforcing each other; the only difference between the scientist and the lab technician is one of degree (or degrees)—neither has contributed much to our understanding of life on earth except knowledge of the means to destroy both. Einstein is reputed to have said, near the end of his career, that he would rather have been a good shoemaker than what he was, a great mathematician. We may take this statement as his confession of participatory guilt in the making of the modern nightmare.

The denunciation of science-technology that I have outlined here, […] should be taken seriously at least as an expression of the fear millions now feel for the plastic-aluminum-electronic-computerized technocracy forming around us, constricting our lives to the dimensions of the machine, divorcing our bodies and souls from the earth, harassing us constantly with its petty and haywire demands.5

Many people who still have a grain of life within their souls feel, instinctively, that something is wrong with modern life, but they may not know what the problems are, nor how to fix them. The Machine has destroyed much of the world. The Gods are the way back to Eden. Only through the Gods, may we find the power to destroy the Machine. How do we come back into touch with the Gods? Perhaps the best way is through the cosmos: we may have destroyed much of the natural beauty on this planet, but the sun and moon are just as resplendent as ever. Scientific knowledge blinds us to the deeper sources of reality, so we need to learn to see beyond science. Lawrence, in a beautiful passage, writes:

The universe is dead for us, and how is it to come to life again? “Knowledge” has killed the sun, making it a ball of gas, with spots; “knowledge” has killed the moon, it is a dead little earth pitted with extinct craters as with small-pox; the machine has killed the earth for us, making it a surface, more or less bumpy, that you travel over. How, out of this, are we to get back the grand orbs of the soul’s heavens, that fill us with unspeakable joy? How are we to get back Apollo, and Attis, Demeter, Persephone, and the halls of Dis? How even see the star Hesperus, or Betelgeuse.

We’ve got to get them back, for they are the world our soul, our greater consciousness lives in. The world of reason and science, the moon, a dead lump of earth, the sun, so much gas with spots, this is the dry and sterile little world the abstracted mind inhabits. The world of our little consciousness, which we know in our pettifogging apartness. This is how we know the world, when we know it apart from ourselves, in the mean separateness of everything. When we know the world in togetherness with ourselves, we know the earth hyacinthine or Plutonic, we know the moon gives us our body as delight upon us, or steals it away, we know the purring of the great gold lion of the sun, who licks at us like a lioness her cubs, making us bold, or else, like the red angry lion, slashes at us with open claws. There are many ways of knowing, there are many sorts of knowledge. But the two great ways of knowing, for man, are knowing in terms of apartness, which is mental, rational, scientific, and knowing in terms of togetherness, which is religious and poetic. The Christian religion lost, in Protestantism finally, the togetherness with the universe, the togetherness of the body, the sex, the emotions, the passions, with the earth and sun and stars.6

We can come to know the Gods through love, through our bodies and souls, and through the cosmos. Religion means to bind back, and, as Lawrence writes above, science, modernity, and the Machine are great sunderers, so to heal the world, we must do it in terms of togetherness, and the truest foundation for all togetherness, from the marriage bond, to the gravitational pull of the sun, is a love of the Gods. Modern religion has largely given into the demands of the Machine, with the oldest and most traditional forms of mystical faiths being the lone holdouts at times. There is much good left in Orthodoxy and Sufism, though they are rather corrupted, but there is very little left of any substance in Protestantism. The three ultimate principles we should all strive to embody are the true, the good, and the beautiful, but none of these has any meaning in relation to man, alone, but only in his relationship to the Divine. To be truly beautiful is to be like a God, to burn with a fire like a phoenix, and to know that one’s soul is connected to the soul of the world. As Klages writes: “Neither the ego nor its deeds are beautiful. Man is beautiful only to the extent that he participates in the eternal soul of the Cosmos. Beauty [apart from the Divine] is always demonic, and the proper objects of our adoration are the gods.”7

Spiral flame

There have been so many gods

that now there are none.

When the One God made a monopoly of it

he wore us out, so now we are godless and unbelieving.

Yet, O my young men, there is a vivifier.

There is that which makes us eager.

While we are eager, we think nothing of it.

Sum, ergo non cogito.

But when our eagerness leaves us, we are godless and full of thought.

We have worn out the gods, and they us.

That pale one, filled with renunciation and pain and white love

has worn us weary of renunciation and love and even pain.

That strong one, ruling the universe with a rod of iron

has sickened us thoroughly with rods of iron and rulers and

strong men.

The All-Wise has sickened us of wisdom.

The weeping mother of god, inconsolable over her son

makes us prefer to be womanless, rather than be wept over.

And that poor makeshift, Aphrodite emerging in a bathing-suit from our

modern sea-side foam

has successfully killed all desire in us whatsoever.

Yet, O my young men, there is a vivifier.

There is a swan-like flame that curls round the centre of space

and flutters at the core of the atom,

there is a spiral flame-tip that can lick our little atoms into fusion

so we roar up like bonfires of vitality

and fuse in broad hard flame of many men in a oneness.

O pillars of flame by night, O my young men

spinning and dancing like flamy fire-sprouts in the dark ahead of the

multitude!

O ruddy god in our veins, O fiery god in our genitals!

O rippling hard fire of courage, O fusing of hot trust

when the fire reaches us, O my young men!

And the same flame that fills us with life, it will dance and burn the house

down

all the fittings and elaborate furnishings

and all the people that go with the fittings and furnishings,

the upholstered dead that sit in deep arm-chairs.8

There may be one God, but there are many Gods. One may primarily worship one God out of the many, but with the knowledge that there are countless others. There is a divine principle beyond even the Gods, namely the primordial Fire, but that is not physical, not anthropomorphic, and is beyond being; therefore it cannot be readily comprehended except by sun-men who have already come into a close relationship with the Gods. Some Gods, such as the Jewish and Muslim Gods, are jealous. Again, there is nothing wrong with that, so long it doesn’t come at the expense of other Gods. If Muslims only want to worship Allah, that is their right, but they should acknowledge the reality of other divine principles and manifestations. The Gods exist even if few believe in them fully and truly. They do not require our belief. It is we who suffer when we stop believing and worshiping. When that happens, the Gods withdraw from us, leaving us spiritually impoverished.

The few Gods that retain some semblance of a following in the modern world have had their faiths so corrupted that some may be doing the opposite of what the God would want when they worship them in the common fashion. Take for instance Christianity: most Christians of today are practicing anti-Christianity, and they incur Christ’s subtle wrath through their abuse of his worship and doctrines.

Ultimately, even if we do not or cannot believe in any of the Gods, there is a life principle pulsing through the universe, and it is that of Fire, greatest of the Gods, antecedent to all else that exists. Everything, from one of our cells, to the great Gods of thunder and lightning, has life because of the Fire. It is the great vivifying and fecundating principle of the cosmos. It may be beyond being, but it does think, feel, and understand: and when the time comes it will destroy the Machine.

Some great mystics may be able to commune directly with the Gods, but for most people the surest route to the Divine is through religious ritual. Modern faiths do away with this at their peril. Protestantism destroys far too much of value in religion. There is much good left in Orthodoxy and Sufism. Sufism has a connection to the cosmos through the daily prayers and lunar calendar. But, we have lost so much. We cannot mechanically revive old symbols, but we need a way to vitally reawaken men and women to ritual, symbol, and archetypes. We must come back into touch with the sun and moon, and we must start praying and sacrificing again. Let us pour some wine out for Dionysus and salute king Helios from a mountain peak. Let us come back into the holy rhythm of days, months, and years, and the cycles within and beyond those periods of time. We need religion and ritual even more than bread, but we, today, sacrifice our greater needs for petty wants. Lawrence describes this in more detail in the following brilliant passage:

The rhythm of the cosmos is something we cannot get away from, without bitterly impoverishing our lives. The early Christians tried to kill the old pagan rhythm of cosmic ritual, and to some extent succeeded. They killed the planets and the zodiac, perhaps because astrology had already become debased to fortune-telling. They wanted to kill the festivals of the year. But the church, which knows that man doth not live by man alone, but by the sun and moon and earth in their revolutions, restored the sacred days and the feasts almost as the pagans had them, and the Christian peasants went on very much as the pagan peasants had gone, with the sunrise pause for worship, and the sunset, and noon, the three great daily moments of the sun: then the new holy day, one in the ancient seven-cycle: then Easter and the dying and rising God, Pentecost, Midsummer Fire, the November dead and the spirits of the grave, then Christmas, then Three Kings. For centuries the mass of people lived in this rhythm, under the Church. And it is down in the mass that the roots of religion are eternal. When the mass of people loses the religious rhythm, that people is dead, without hope.—But Protestantism came and gave a great blow to the religious and ritualistic rhythm of the year, in human life. Nonconformity almost finished the deed. Now you have a poor, blind, disconnected people with nothing but politics and bank-holidays to satisfy the eternal human need of living in ritual adjustment to the cosmos in its revolutions, in eternal submission to the greater laws. […] Mankind has got to get back to the rhythm of the cosmos[…]

Man has little needs and deeper needs. We have fallen into the mistake of living from our little needs, till we have almost lost our deeper needs in a sort of madness. There is a little morality, which concerns persons and the little needs of man: and this, alas, is the morality we live by. But there is a deeper morality, which concerns all womanhood, all manhood, and nations, and races, and classes of men. This greater morality affects the destiny of mankind over long stretches of time, applies to man’s greater needs, and is often in conflict with the little morality of the little needs. […] [T]he greatest need of man is the renewal forever of the complete rhythm of life and death, the rhythm of the sun’s year, the body’s year of a life-time, and the greater year of the stars, the soul’s year of immortality. This is our need, our imperative need. It is a need of the mind and soul, body, spirit and sex: all. It is no use asking for a Word to fulfil such a need. No Word, no Logos, no Utterance will ever do it. The Word is uttered, most of it. We need only pay true attention. But who will call us to the Deed, the great Deed of the seasons and the year, the Deed of the soul’s cycle, […] the little Deed of the moon’s wandering, the bigger Deed of the sun’s, and the biggest, of the great still stars? It is the Deed of life we have now to learn: we are supposed to have learnt the Word, and alas, look at us. Word-perfect we may be, but Deed-demented. Let us prepare now for the death of our present “little” life, and the re-emergence in a bigger life, in touch with the moving cosmos.

It is a question, practically, of relationship. We must get back into relation, vivid and nourishing relation to the cosmos and the universe. The way is through daily ritual, and the re-awakening. We must once more practise the ritual of dawn and noon and sunset, the ritual of the kindling fire and pouring water, the ritual of the first breath, and the last. […] To these rituals we must return: or we must evolve them to suit our needs. For the truth is, we are perishing for lack of fulfilment of our greater needs, we are cut off from the great sources of our inward nourishment and renewal, sources which flow eternally in the universe. Vitally, the human race is dying. It is like a great uprooted tree, with its roots in the air. We must plant ourselves again in the universe.

It means a return to ancient forms. But we shall have to create these forms again, and it is more difficult than the preaching of an evangel. The Gospel came to tell us we were all saved. We look at the world today and realise that humanity, alas, instead of being saved from sin, whatever that may be, is almost completely lost, lost to life, and near to nullity and extermination. We have to go back, a long way, before the idealist conceptions began, before Plato, before the tragic idea of life arose, to get on our feet again. For the gospel of salvation through the Ideals and escape from the body coincided with the tragic conception of human life. […] Back, before the idealist religions and philosophies arose and started man on the great excursion of tragedy. The last three thousand years of mankind have been an excursion into ideals, bodilessness, and tragedy, and now the excursion is over. And it is like the end of a tragedy in the theatre. The stage is strewn with dead bodies, worse still, with meaningless bodies, and the curtain comes down.

But in life, the curtain never comes down on the scene. There the dead bodies lie, and the inert ones, and somebody has to clear them away, somebody has to carry on. It is the day after. Today is already the day after the end of the tragic and idealist epoch. Utmost inertia falls on the remaining protagonists. Yet we have to carry on.9

As difficult as this reawakening may seem, it is not only possible, but inevitable. The ways and ideas of modernity, like those of all previous eras, are transient, nothing but a blip; and ours is an aberration from all its predecessors. “‘[A]ncient life’ is far more deeply conscious than you can even imagine. And its discipline goes into regions where you have no existence.”10 We can reawaken ancient life, but in a new and vital way. This was one of Lawrence’s great projects, and he hoped it could be put into practice in Rananim. Perhaps now it is time for all the remaining men and women who want to be free of the Machine to flee to Rananim and let the rest of civilization suffer its fate. Fire cleanses, and having the house burn down is better than trying to save a rotten system, beholden to the Machine. As Jeffers writes:

The squid, frightened or angry, shoots darkness

Out of her ink-sack; the fighting destroyer throws out a smoke-screen;

And fighting governments produce lies.

But squid and warship do it to confuse the enemy, governments

Mostly to stupefy their own people.

It might be better to let the roof burn and the walls crash

Than save a nation with floods of excrement.11

Space

Space, of course, is alive

that’s why it moves about;

and that’s what makes it eternally spacious and unstuffy.

And somewhere it has a wild heart

that sends pulses even through me;

and I call it the sun;

and I feel aristocratic, noble, when I feel a pulse go through me

from the wild heart of space, that I call the sun of suns.12

Everything lives. Even the black vastness of space is alive. And everything that lives, moves. All that is, is in eternal flux. The core of the cosmos is the Fire, and the Fire gives life to everything in existence. When Lawrence refers to the sun, he refers directly to the sun, as a symbol, but also to the subtle sun-principle or fire of the Fire, which pulses and reverberates through all things. When one feels the life of the Fire, one comes closer to the Gods, and that person is an aristocrat on the face of the earth, a sun-man. The farther back we go in history, the more profound the religious wisdom, and the closer the peoples were to religious truth. The more “advanced” humans became in engineering and rational thinking, the more atrophied their spiritual centers became. Lawrence and Klages both knew that the pre-Orphic peoples of the Mediterranean were much closer to the divine truths than even the later Aegean civilizations. Lawrence writes of his love of the ancient conceptions of life and cosmology:

I love the pre-Christian heavens—the planets that became such a prison of the consciousness—and the ritual year of the zodiac. But I like the heavens best pre-Orphic, before there was any “fall” of the soul, and any redemption. The soul only “fell” about 500 B.C. or thereabouts, with the Orphics and late Egypt. […] In my opinion the great pagan religions of the Aegean, and Egypt and Babylon, must have conceived of the “descent” as a great triumph, and each Easter of the clothing in flesh as a supreme glory, and the Mother Moon who gives us our body as the supreme giver of the great gift, hence the very ancient Magna Mater in the East. This “fall” into Matter (matter wasn’t even conceived in 600 B.C.—no such idea) this “entombment” in the “envelope of flesh” is a new and pernicious idea arising about 500 B.C. into distinct cult-consciousness—and destined to kill the grandeur of the heavens altogether at last.13

Ancient peoples were most emphatically not uncivilized. Just read through Homer’s epics with feeling: you can’t help but realize that the ancient Greeks were far more civilized than we are today. In the following passage Lawrence corrects the misconception that ancients were somehow less intelligent than moderns:

In the days before Homer, men in Europe were not mere brutes and savages and prognathous monsters: neither were they simple-minded children. Men are always men, and though intelligence takes different forms, men are always intelligent: they are not empty brutes, or dumb-bells en masse.14

For the ancients, there was no such thing as dead matter. Ancient Greeks, Native Americans, and other old religious groups knew that even mountains, even thunder lives. All is alive, and all that is alive is in flux and is filled full of divine energy. The entire cosmos is alive, and within the cosmos, trees, mountains, galaxies, and the human soul all pulse with the life granted by the Gods through the primordial Fire. As Lawrence writes:

Space, like the world, cannot but move. And like the world, there is an axis. And the axis of our worldly space, when you enter, is a vastness where even the trees come and go, and the soul is at home in its own dream, noble and unquestioned.15

Within the living universe, all things are connected. Humans, having the gift of free will, have the choice to sunder those connections or to come into touch with all that is—with love and tenderness. Ancients were deeply in touch with the animals, trees, and the earth they called home. But most moderns are sunderers; and sundering is a form of suicide, because it cuts one off from the life-force. As Lawrence writes:

We are unnaturally resisting our connection with the cosmos, with the world, with mankind, with the nation, with the family. All these connections are, in the Apocalypse, anathema, and they are anathema to us. We cannot bear connection. That is our malady. We must break away, and be isolate. We call that being free, being individual. Beyond a certain point, which we have reached, it is suicide. Perhaps we have chosen suicide. Well and good.16

Thus our modern freedom can itself be a form of prison, just as many forms of modern religions. Both the freedom from religion and many modern religions can also become a form of imprisonment. The noxious concept of sin poisoned religion, and poisoned man’s relationship with the Divine. But sin is a relatively recent concept, and ancient religions had no concept of this deadly principle. As Klages writes:

The idea of “sin” was quite alien to the pagan world. The ancient pagans knew the gods’ hatred as well as their revenge, but they never heard of punishment for “sin.” The ancient philosophers did understand something of the “good,” but when they employed this expression, they were certainly not endorsing the concept of the “sinless.” Quite the contrary: they were actually speaking of the pursuit of every type of excellence.17

The ancients were not immoral peoples (though there are always individual exceptions). Quite the contrary, they had a purer morality, because they did good not out of fear of punishment, but out of a deep love of the Divine and all of creation. To come back to ancient ways, we need to undo the sundering, and start a new coming-together. This cannot be forced, but must come through tenderness and a love of the Gods and creation. The people to accomplish this are a special breed of sun-men, the epic poets. As Klages writes:

The genuine artist does not traffic in fictions. The demonic powers that he sings, speaks, or forms, are there. In plastic embodiment the wave is image and event.—The cosmic epic poet reunites that which has been sundered: the epic world-poem to the “ardor of the eye.” He steps out of the modern age and spins the golden threads of the eternal flux. A god and a lightning-bolt will not suffice—the entire history of the gods must unfold before his gaze.18

Lawrence was the Homer for our times. Let us listen to him, and allow him to guide us back to home, just as the muses guided Odysseus back to Ithaca.

The Wandering Cosmos.

Oh, do not tell me the heavens as well are a wheel.

For every revolution of the earth around the sun

is a footstep onwards, onwards, we know not whither

and we do not care,

but a step onwards in untravelled space,

for the earth, like the sun, is a wanderer.

Their going round each time is a step

onwards, we know not whither,

but onwards, onwards, for the heavens are wandering

the moon and the earth, the sun, Saturn and Betelgeuse, Vega and Sirius

and Altair

they wander their strange and different ways in heaven

past Venus and Uranus and the signs.

For life is a wandering, we know not whither, but going.

Only the wheel goes round, but it never wanders.

It stays on its hub.19

The previous poem from Lawrence discloses an important truth: all is in flux, namely, all wanders, but wandering / being in flux is not only not the same as mechanical motion, but precisely its opposite. Cogs, gears, and wheels go round and round mindlessly, and the gears of the Machine in all its complexity and ever-expanding potency threaten to grind all of us into exceedingly impotent enablers. Despite that threat, the cosmic flux can still suffuse all of us with life. Either we give in to the Machine and sacrifice life on the altar of death, or we give up our modern conceit that technology offers salvation and start afresh from old wisdom. As Lawrence states, “We must go back to pick up old threads. We must take up the old, broken impulse that will connect us with the mystery of the cosmos again, now we are at the end of our own tether. We must do it.”20 We need to do this desperately. Unless we can recover the mystery and wonder of Nature, we are lost. The irony is that the more we know, scientifically, the less we are able to be. To look up at the planets with a great, childlike sense of wonder is a joy most moderns never experience, and that is a tragedy. For the ancients:

The wandering planets were always a great mystery to men, especially in the days when he lived breast to breast with the cosmos, and watched the moving heavens with a profundity of passionate attention quite different from any form of attention today.21

Bibliography

D. H. Lawrence (2013). The Poems, Cambridge University Press.

D. H. Lawrence (2018). Kangaroo, The Text Publishing Company.

D. H. Lawrence (1995). Apocalypse, Penguin Books.

D. H. Lawrence (2009). A Propos of "Lady Chatterley's Lover", Penguin Books.

D. H. Lawrence (1999). Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays, Cambridge University Press.

D. H. Lawrence (2002). The Letters of D. H. Lawrence, Cambridge University Press.

D. H. Lawrence (2002a). Sketches of Etruscan Places and Other Italian Essays, Cambridge University Press.

D. H. Lawrence (2002a). The Plumed Serpent, Cambridge University Press.

Edward Abbey (2005). The Best of Edward Abbey, Counterpoint Press.

Jeffers, Robinson (1988). The Collected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers, Stanford University Press.

Ludwig Klages (2015). Cosmogonic Reflections, Arktos.

D. H. Lawrence (2013 p. 378)

D. H. Lawrence (2018 p. 161)

D. H. Lawrence (1995 p. 46)

D. H. Lawrence (2013 pp. 379-380)

Edward Abbey (2005 p. 227)

D. H. Lawrence (2009 p. 331)

Ludwig Klages (2015 p. 26)

D. H. Lawrence (2013 pp. 381-382)

D. H. Lawrence (2009 pp. 328-330)

D. H. Lawrence (1999 p. 243)

Jeffers, Robinson (1988 p. 126)

D. H. Lawrence (2013 p. 456)

D. H. Lawrence (2002 pp. 544-545)

D. H. Lawrence (2002a p. 177)

D. H. Lawrence (2002a p. 126)

D. H. Lawrence (1995 p. 148)

Ludwig Klages (2015 p. 11)

Ludwig Klages (2015 p. 53)

D. H. Lawrence (2013 p. 627)

D. H. Lawrence (2002a p. 138)

D. H. Lawrence (1995 p. 136)