Childhood, Youth, and Education

The Machine Will Never Triumph, part thirty-five

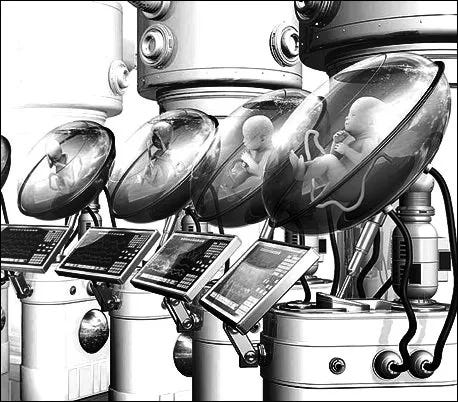

Poor young things—

The young today are born prisoners

poor things, and they know it.

Born in a universal workhouse,

and they feel it.

Inheriting a sort of confinement

work, and prisoners’ routine

and prisoners’ flat, ineffectual pastime.1

It is a marvelous thing to be born, and one should feel graced with a gift from the Gods to have been born at any time, but of all the times to have been born, the present is the worst we have known since the beginning of historical records. To be born today means going from the womb to compulsory schooling, and from compulsory schooling, straight to the workhouse. Children today are prisoners in the jail houses their parents have built. Even the recreational activities of moderns is paltry and insipid compared to ancient forms of play. Adults force children to suffer through school only so that they may suffer through the rest of their lives at work. For the few who are lucky enough to retire, many are too frail to enjoy it, and others waste away their precious years in worthless activities, such as watching the news. Even today in third world countries, one sees the elders communing together in joy through tea, coffee, and sport, but in the developed west, life is more barren than the Antarctic Plateau.

When one, rarely, retains enough childhood wonder into early adulthood, it is usually crushed out by college and then the workforce. One quickly learns that universities are not places to seek enlightenment, but are education factories. Modern universities are a far cry from the austere and hallowed institutions of the Middle Ages. Lawrence writes of this as follows:

What good was this place, this college? What good was Anglo-Saxon, when one only learned it in order to answer examination questions, in order that one should have a higher commercial value later on? She was sick with this long service at the inner commercial shrine. Yet what else was there? Was life all this, and this only? Everywhere, everything was debased to the same service. Everything went to produce vulgar things, to encumber material life[…] College was barren, cheap, a temple converted to the most vulgar, petty commerce. Had she not gone to hear the echo of learning pulsing back to the source of the mystery?—The source of mystery! And barrenly, the professors in their gowns offered commercial commodity that could be turned to good account in the examination room; ready-made stuff too, and not really worth the money it was intended to fetch; which they all knew.2

Society has been set up in such a way as to squeeze all the life and vitality out of children so that they become complacent workers, cogs in the system, and grist in the Machine. But, Lawrence, always defiant, declares, stridently: “I defy you, oh society, to educate me or to suppress me, according to your dummy standards.”3 The instruments the Machine uses to destroy children are called schools. Lawrence’s views on modern schooling are as follows:

Our business, at the present, is to prevent at all cost the young idea from shooting. The ideal mind, the brain, has become the vampire of modern life, sucking up the blood and the life. There is hardly an original thought or original utterance possible to us. All is sickly repetition of stale, stale ideas.

Let all schools be closed at once. Keep only a few technical training establishments, nothing more. Let humanity lie fallow, for two generations at least. Let no child learn to read, unless it learns by itself, out of its own individual persistent desire.4

Children should cultivate love, wonder, joy, and imagination, not logical thinking and skills in math and science. Society should cultivate the hearts and souls of children and not just their heads. As such, Lawrence is correct, and as a corrective, compulsory schooling should be ended, and schools should be closed immediately. Parents should educate children in basic matters and teach them essential earth skills, such as ancient forms of farming, along with basic things every person should know such as reverence for, and ways of expressing reverence toward, the higher orders of Reality—the Gods. The only schools should be small trade schools that are run by guilds of craftsmen, which would teach arts to children who are so inclined. Importantly, society should actively prevent access to those sciences that are most dangerous and have led to the ascendency of the Machine, namely certain forms of math, physics, and engineering, along with psychology, and various modern ideologies. As Joseph Conrad writes:

The demonstration must be against learning—science. But not every science will do. The attack must have all the shocking senselessness of gratuitous blasphemy. Since bombs are your means of expression, it would be really telling if one could throw a bomb into pure mathematics.5

An actual “bomb” is not meant in the above passage, but a metaphysical bomb. Lawrence penned an essay titled Surgery for the novel—or a bomb, and that is the kind of bomb that is meant, namely a literary, prophetic utterance that collapses empires. Jesus Christ was just such a bomb, and his Word is still sending out shock waves to this day. Lawrence could—if we allow his words to penetrate our hearts—have the same impact.

Building upon the preceding statements, Lawrence lays out the claim that modern education, along with modern ideologies, have led to an ascendency of the head at the expense of the heart. Once the head takes over, untempered by the heart and soul, ideas, monstrous ideas, spring forth, and the human population becomes one large mental abstraction, working away automatically without any real, directly lived life. Lawrence writes:

[G]eneral education should be suppressed as soon as possible. We have fallen into a state of fixed, deadly will. Everything we do and say to our children in school tends simply to fix in them the same deadly will, under the pretence of pure love. Our idealism is the clue to our fixed will. Love, beauty, benevolence, progress, these are the words we use. But the principle we evoke is a principle of barren, sanctified compulsion of all life. We want to put all life under compulsion. “How to outwit the nerves,” for example.—And therefore, to save the children as far as possible, elementary education should be stopped at once.

No child should be sent to any sort of public institution before the age of ten years[…] The fact is, our process of universal education is to-day so uncouth, so psychologically barbaric, that it is the most terrible menace to the existence of our race. We seize hold of our children, and by parrot-compulsion we force into them a set of mental tricks. By unnatural and unhealthy compulsion we force them into a certain amount of cerebral activity. And then, after a few years, with a certain number of windmills in their heads, we turn them loose, like so many inferior Don Quixotes, to make a mess of life. All that they have learnt in their heads has no reference at all to their dynamic souls. The windmills spin and spin in a wind of words, […] And round they skelter, after their own tails. That is, when they are not forced to grind out their lives for a wage. Though work is the only thing that prevents our masses from going quite mad.

To tell the truth, ideas are the most dangerous germs mankind has ever been injected with. They are introduced into the brain by injection, in schools and by means of newspapers, and then we are done for.

An idea which is merely introduced into the brain, and started spinning there like some outrageous insect, is the cause of all our misery today. Instead of living from the spontaneous centers, we live from the head. We chew, chew, chew at some theory, some idea. We grind, grind, grind in our mental consciousness, till we are beside ourselves. Our primary affective centers, our centers of spontaneous being, are so utterly ground round and automatized that they squeak in all stages of disharmony and incipient collapse. We are a people—and not we alone—of idiots, imbeciles and epileptics, and we don’t even know we are raving.6

In fact, humanity was happiest and best off before history, before modern science, before modern religion, and even before literacy. Oh how the ancients sang of the Gods as if they could see them—which they probably did. “The great mass of humanity should never learn to read and write—never.”7 Some can and should read, but most people would be better off, smarter, and have better memory if they relied on oral communication. Rather than leading us into savagery, this would make us more gentle and tender. As Lawrence writes, it is modern education that turns us into violent savages:

The top and bottom of it is, that it is a crime to teach a child anything at all, school-wise. It is just evil to collect children together and teach them through the head. It causes absolute starvation in the dynamic centres, and sterile substitute of brain knowledge is all the gain. The children of the middle classes are so vitally impoverished, that the miracle is they continue to exist at all. The children of the lower classes do better, because they escape into the streets. But even the children of the proletariat are now infected.

And, of course, as my critics point out, under all the school-smarm and newspaper-cant, man is today as savage as a cannibal, and more dangerous. The living dynamic self is denaturalised instead of being educated.

We talk about education—leading forth the natural intelligence of a child. But ours is just the opposite of leading forth. It is a ramming in of brain facts through the head, and a consequent distortion, suffocation, and starvation of the primary centres of consciousness. A nice day of reckoning we’ve got in front of us.8

There is a role for non-compulsory education, but it should do the opposite of modern education: “[B]oth desire and impulse tend to fall into mechanical automatism: to fall from spontaneous reality into dead or material reality. All our education should be a guarding against this fall.”9 Rather than saving the world and protecting the young, “[o]ur system of education today threatens our whole social existence tomorrow. We should be wise if by decree we shut up all elementary schools at once, and kept them shut. Failing that, we must look around for a better system, one that will work.”10 What better system would that be? It is hard to say, precisely, but Lawrence points us in the right direction:

[T]he only thing to do is to undertake the responsibility with good grace. What responsibility? The responsibility of establishing a new system: a new, organic system, free as far as ever it can be from automatism or mechanism: a system which depends on the profound spontaneous soul of men.

How to begin? Is it any good having revolutions and cataclysms? Who knows. Revolutions and cataclysms may be inevitable. But they are merely hopeless and catastrophic unless there come to life the germ of a new mode. And the new mode must be incipient somewhere. And therefore, let us start with education.11

So, when we decide that things must change, and people join round the sun-men in Rananim, one of the first tasks is to completely change the way education is both thought of and enacted. True education should cultivate a person’s individuality, it should ignite their spark, and allow their inner daemon to grow strong, whereas modern education simply seeks to make man a nothing, a nobody, an automatic cog in the Machine. Lawrence writes:

A real individual has a spark of danger in him, a menace to society. Quench this spark and you quench the individuality, you obtain a social unit, not an integral man. All modern progress has tended, and still tends, to the production of quenched social units: dangerless beings, ideal creatures!12

So, how do we educate a child? Lawrence has some sagacious advice:

How to begin to educate a child.—First rule, leave him alone. Second rule, leave him alone. Third rule, leave him alone. That is the whole beginning.13

Young fathers

Young men, having no real joy in life and no hope in the future

how can they commit the indecency of begetting children

without first begetting a new hope for the children to grow up to?

But then, you need only look at the modern perambulator

to see that a child, as soon as it is born,

is put by parents into its coffin.14

There are already too many people in the world. Men and women should not have large families, should limit themselves to a single child, and should only have a child if it will be raised right, according to Lawrencian principles. As Lawrence makes clear, children today are stillborn, they are the living dead. To exit the anaesthetized womb only to be greeted by a flood of electric lights, to be vaccinated, and then to be herded into schools to have all individuality expunged is the fate of the children of today, and it is a sad fate indeed. Parents want better things for their children, but today each succeeding generation becomes more debased. “Very few people surpass their parents nowadays, and attain any individuality beyond them. Most men are half-born slaves: the little soul they are born with just atrophies, and merely the organism swells into manhood, like big potatoes.”15 Truly, it is a sad state of affairs. All the things modern men look to for joy are just substitutes for the real thing. Few things are as joyful as biting into a piece of fresh, ripe fruit straight from the tree, but even fruit today tastes like cardboard. As Lawrence writes:

[T]here is substitute for everything—life-substitute—just as we have butter-substitute, and meat-substitute, and sugar-substitute, and leather-substitute, and silk-substitute, so we have life-substitute[…]

The poor modern brat […] is really too pathetic to contemplate[…] [T]he little devil will grow up and beget other similar little devils of his own, to invent more aeroplanes and hospitals and germ-killers and food-substitutes and poison gases. The problem of the future is a question of the strongest poison-gas[…]

Oh, ideal humanity, how detestable and despicable you are! And how you deserve your own poison-gases! How you deserve to perish in your own stink.16

This passage could have been written by Lawrence yesterday. Rather than learning from Covid, and making the decision to live better, humanity has collectively decided to further withdraw into cyberspace, and to flood the world with even more vaccines, more substitute products, and far more germ killers, which are poisons and kill their users slowly. The children born today are heirs to this mess, and it is producing monsters. The children of today are able to interact with machines better than people, and it is making them ever more machine-like. R. S. Thomas describes this in the following poem:

Mostly it was wars

With their justification

Of the surrender of values

For which they fought. Between

Them they laid their plans

For the next, exempted

From compact by the machine’s

Exigencies. Silence

Was out of date; wisdom consisted

In a revision of the strict code

Of the spirit. To keep moving

Was best; to bring the arrival

Nearer departure; to synchronise

The applause, as the public images

Stepped on and off the stationary

Aircraft. The labour of the years

Was over; the children were heirs

To an instant existence. They fed the machine

Their questions, knowing the answers

Already, unable to apply them.17

Bibliography

Conrad, Joseph. The Secret Agent. Edited by Michael Newton. London: Penguin Books, 2007.

Lawrence, D. H. Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious. Edited by Bruce Steele. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

———. Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays. Edited by Michael Herbert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

———. Studies in Classic American Literature. Edited by Ezra Greenspan, Lindeth Vasey, and John Worthen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

———. The Poems. Edited by Christopher Pollnitz. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

———. The Rainbow. London: Everyman’s Library, 1993.

Thomas, R. S. Collected Poems. London: Orion Books, 2000.

D. H. Lawrence, The Poems, ed. Christopher Pollnitz, vol. 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 450.

D. H. Lawrence, The Rainbow (London: Everyman’s Library, 1993), 404.

D. H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature, ed. Ezra Greenspan, Lindeth Vasey, and John Worthen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 20.

D. H. Lawrence, Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious, ed. Bruce Steele (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 105–6.

Joseph Conrad, The Secret Agent, ed. Michael Newton (London: Penguin Books, 2007), 27.

Lawrence, Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious, 114–15.

ibid., 118.

ibid., 123.

D. H. Lawrence, Reflections on the Death of a Porcupine and Other Essays, ed. Michael Herbert (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 79.

ibid., 100.

ibid., 112.

ibid., 114.

ibid., 121.

Lawrence, The Poems, 1:453.

Lawrence, Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious and Fantasia of the Unconscious, 76–77.

ibid., 162.

R. S. Thomas, Collected Poems (London: Orion Books, 2000), 217.